BRUCELLOSIS

What is Brucellosis and how is it transmitted?

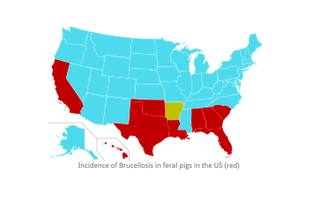

Swine brucellosis is a contagious disease in pigs caused by the bacteria, Brucella suis. The disease spreads in semen during breeding and by ingesting, inhaling, or eye contact with bacteria in milk, reproductive fluids, placenta, aborted fetuses and urine. The disease primarily occurs in adult pigs which show non-specific infertility, abortion or lack of sexual drive. Boars can show signs of orchitis, lameness, arthritis, abscesses and posterior paralysis. There is no treatment for the disease and no effective vaccine. This horrible disease can find its way in an otherwise brucellosis free herd by a +feral pig making contact or leaving any of the potential body fluids to expose brucellosis free pigs. It is said the only way to control the risk with high prevalence of wild pigs (which are known to be infected or carriers) is to implement biosecurity measures that prevents contact with wildlife such as double hare- or wild boar-proof fencing. Unfortunately, there is no way to control or reduce infected wildlife reservoirs.

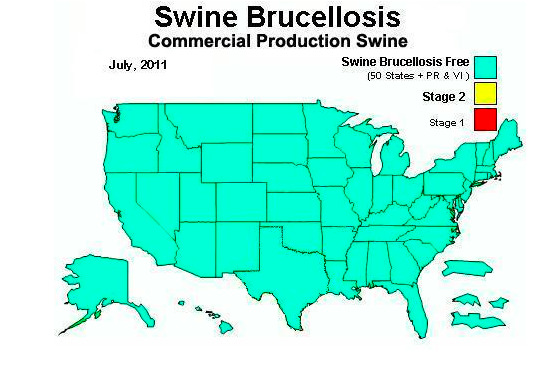

Clinical manifestations of brucellosis in pigs vary but are similar to those seen in cattle and goats. Although the disease is often self-limiting, it remains in some herds for years. Brucellosis caused by Brucella suis rarely occurs in domestic animals other than pigs. Epidemics of brucellosis in people have been reported among packing-house workers, and the usual source is infected pigs. The prevalence in the USA is sometimes high among feral pigs. The incidence of swine brucellosis among domesticated animals in the USA is very low. Currently there are no known infected domestic swine herds.

After exposure to B suis, pigs develop a bacteremia that may persist for as long as 90 days. During and after the bacteremia, localization may occur in various tissues. Signs depend considerably on the site(s) of localization. Common manifestations are abortion, temporary or permanent sterility, orchitis, lameness, posterior paralysis, spondylitis, and occasionally metritis and abscess formation. B suis is usually spread mainly by ingestion of infected tissues or fluids. Infected boars may transmit the disease during service; the organism can be recovered from semen.

How do you know if a pig has this disease?

Pigs raised for breeding purposes are sources of infection. Suckling pigs may become infected from sows but most reach weanling age without becoming infected.

The principal means of diagnosis in pigs is the brucellosis card (rose bengal) test; however, other serum agglutination tests or complement fixation tests have been used. It is generally accepted that the tests have limitations in detecting brucellosis in individual pigs. Thus, entire herds or units of herds, rather than individual pigs, must be tested in any control program. Low agglutinin titers are seen in almost any size herd, regardless of infection status, and a few infected pigs may have no detectable titer. The card test is usually more accurate than conventional agglutination tests. Supplemental tests designed for cattle may also be used for pigs.

Sources:

http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/reproductive_system/brucellosis_in_large_animals/brucellosis

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam/new-vdpam-employees/food-supply-veterinary-medicine/swine/swine-diseases/brucellosis-swine-bruhttp://www.thepigsite.com/diseaseinfo/20/brucellosis/

USDA publication regarding brucellosis in the USA.

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_dis_spec/swine/downloads/sbruumr.pdf_

Swine brucellosis is a contagious disease in pigs caused by the bacteria, Brucella suis. The disease spreads in semen during breeding and by ingesting, inhaling, or eye contact with bacteria in milk, reproductive fluids, placenta, aborted fetuses and urine. The disease primarily occurs in adult pigs which show non-specific infertility, abortion or lack of sexual drive. Boars can show signs of orchitis, lameness, arthritis, abscesses and posterior paralysis. There is no treatment for the disease and no effective vaccine. This horrible disease can find its way in an otherwise brucellosis free herd by a +feral pig making contact or leaving any of the potential body fluids to expose brucellosis free pigs. It is said the only way to control the risk with high prevalence of wild pigs (which are known to be infected or carriers) is to implement biosecurity measures that prevents contact with wildlife such as double hare- or wild boar-proof fencing. Unfortunately, there is no way to control or reduce infected wildlife reservoirs.

Clinical manifestations of brucellosis in pigs vary but are similar to those seen in cattle and goats. Although the disease is often self-limiting, it remains in some herds for years. Brucellosis caused by Brucella suis rarely occurs in domestic animals other than pigs. Epidemics of brucellosis in people have been reported among packing-house workers, and the usual source is infected pigs. The prevalence in the USA is sometimes high among feral pigs. The incidence of swine brucellosis among domesticated animals in the USA is very low. Currently there are no known infected domestic swine herds.

After exposure to B suis, pigs develop a bacteremia that may persist for as long as 90 days. During and after the bacteremia, localization may occur in various tissues. Signs depend considerably on the site(s) of localization. Common manifestations are abortion, temporary or permanent sterility, orchitis, lameness, posterior paralysis, spondylitis, and occasionally metritis and abscess formation. B suis is usually spread mainly by ingestion of infected tissues or fluids. Infected boars may transmit the disease during service; the organism can be recovered from semen.

How do you know if a pig has this disease?

Pigs raised for breeding purposes are sources of infection. Suckling pigs may become infected from sows but most reach weanling age without becoming infected.

The principal means of diagnosis in pigs is the brucellosis card (rose bengal) test; however, other serum agglutination tests or complement fixation tests have been used. It is generally accepted that the tests have limitations in detecting brucellosis in individual pigs. Thus, entire herds or units of herds, rather than individual pigs, must be tested in any control program. Low agglutinin titers are seen in almost any size herd, regardless of infection status, and a few infected pigs may have no detectable titer. The card test is usually more accurate than conventional agglutination tests. Supplemental tests designed for cattle may also be used for pigs.

Sources:

http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/reproductive_system/brucellosis_in_large_animals/brucellosis

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam/new-vdpam-employees/food-supply-veterinary-medicine/swine/swine-diseases/brucellosis-swine-bruhttp://www.thepigsite.com/diseaseinfo/20/brucellosis/

USDA publication regarding brucellosis in the USA.

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_dis_spec/swine/downloads/sbruumr.pdf_

Treatment:

Unfortunately, based on the present lack of effective tools to manage the disease, whole-herd depopulation appears to be the only viable option to eradicate brucellosis from domestic swine herds. As serological; surveillance is best performed in swine on a herd basis, regulatory efforts to control or eradicate B. suis in swine should be directed toward herds, rather than individual animals. Biosecurity of B. suis-free herds is paramount to prevent introduction or reintroduction from wildlife or other infected farms.

In absence of total depopulation (euthanizing ALL pigs exposed), antibiotic alone or in combination with test and slaughter, is the only suitable alternative to minimize the clinical and economical impacts of this disease. However, as no published references are available on the efficacy of antibiotics for treating brucellosis in pigs, publications treating brucellosis in other animal species and humans are the only standard for devising porcine therapies. This method of control is NOT validated by published experimental data.

Source: Diseases of Swine, 10th edition

Unfortunately, based on the present lack of effective tools to manage the disease, whole-herd depopulation appears to be the only viable option to eradicate brucellosis from domestic swine herds. As serological; surveillance is best performed in swine on a herd basis, regulatory efforts to control or eradicate B. suis in swine should be directed toward herds, rather than individual animals. Biosecurity of B. suis-free herds is paramount to prevent introduction or reintroduction from wildlife or other infected farms.

In absence of total depopulation (euthanizing ALL pigs exposed), antibiotic alone or in combination with test and slaughter, is the only suitable alternative to minimize the clinical and economical impacts of this disease. However, as no published references are available on the efficacy of antibiotics for treating brucellosis in pigs, publications treating brucellosis in other animal species and humans are the only standard for devising porcine therapies. This method of control is NOT validated by published experimental data.

Source: Diseases of Swine, 10th edition

Let me add, as of Nov 2011, the USA has been deemed Brucellosis free versus an older outdated picture where there was still a problem. This is just one of the reasons many states require CVI (certificate of veterinarian inspection also referred to as a health certificate) to be sure this disease doesn't get introduced into disease free states/regions.

You can not tell by looking at this group of pigs posted above, but the whole herd tested positive for brucellosis. In some countries, it is an epidemic. Click this link to read more about it. http://globalbiodefense.com/brucellosis