Mini Pig Seizures

Seizures: What should I look for?

There are many causes for seizures in mini pigs. Seizures is not a disease, but an effect of another disease. Epilepsy is a disease and one of the effects of that disease is seizures, for example.

A seizure is any sudden and uncontrolled movement of the animal's body caused by abnormal brain activity. Seizures may be very severe and affect all of the body, or quite mild, affecting only a portion of the pet. The pet may or may not seem conscious or responsive, and may urinate or have a bowel movement.

Seizure activity that lasts longer than 3 to 5 minutes can cause severe side effects, such as fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) or brain (cerebral edema). A dramatic rise in body temperature (hyperthermia) can also result, causing internal organ damage.

Seizures can be caused by epilepsy, toxins, low blood sugar, brain tumors and a host of other medical conditions. Your veterinarian can help you determine the cause of seizures in your pet, and if necessary can refer you to a specialist to help with the diagnosis or treatment of seizures. In general, animals less than one year of age typically have seizures due to a birth defect such as hydrocephalus (water on the brain) or a liver defect called a portosystemic shunt (among others). Animals that have their first seizure between 1 and 5 years of age typically suffer from epilepsy, while those over 5 years of age often have another medical condition causing the seizures such as a brain tumor, stroke or low blood sugar. This isn't necessarily the case for mini pigs though, they can have seizure disorders at any time with an unknown cause. These are general guidelines, however, and they may or may not apply to your pig.

All pigs that have a seizure should have lab tests to help diagnose the underlying cause, and make sure their organs can tolerate any medications that may be needed to control seizures. Once underlying diseases are ruled out by your veterinarian, some pets require medications such as phenobarbital or potassium bromide, among others, to control seizures. These medications may require frequent dose adjustments and monitoring of blood levels, so it is best to have an open and honest discussion with your veterinarian about the effort and costs involved in treating your pig for seizures.

Because the diagnostic testing isn't typically done on pigs as it is on humans, often times, it's difficult to pinpoint the cause unless your pig is diagnosed with an illness or disease with a known history of causing seizures. A dietary change or accidental ingestion of sodium rich food without access to fresh water can lead to seizures. Water deprivation also sometimes called "salt toxicity" is the usual cause for that particular situation. There are some pigs that may have some kind of genetic or congenital defect within the brain that causes seizures. There have been cases when other medical issues are compounded and complicated resulting in seizures or contributing to seizure activity. There are febrile seizures that are seizures caused by having a high fever. Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) has been known to cause seizures in mini pigs as well, especially piglets who aren't able to mobilize the low glycogen reserves stored in the liver to provide the rest of the body with adequate levels of glucose in the blood. Therefore, it is especially important that piglet stays with mom so he/she is able to nurse and receive the appropriate amounts of lactose from mother’s milk. If a piglet cannot obtain sufficient lactose to maintain its energy output, it runs out of energy, its body temperature drops and ultimately it goes into a coma and dies. If your pig is actively seizing, your pig needs to be seen by a vet.

Keep a journal of when the seizures are occurring, what your pig was doing beforehand, foods your pig has eaten and anything else pertinent. Vaccinations within the last 30 days, parasite medication or any other medication including supplements within the last 30 days, exposure to any toxic substances, anything that may be related to why your pig is having seizures would be helpful to your vet who will be trying to determine the cause. Seizure activity can happen in pigs for the same reason it happens in dogs and cats -- and idiopathic epilepsy is common in the smaller breeds of pigs. If blood work is normal, sodium is low, then generally pigs will be treated for meningitis (also common in small breeds of pigs) with an antibiotic and an anti inflammatory, and then start these pigs on phenobarbital and, in some cases, KBr (Potassium Bromide).

There are also a few different types of seizures that a pig can have. You may see the classic inability to control bodily function seizure. You also have seizures that aren't as visibly noticeable and consists of the pig just staring off into space, looking as if they were in a trance or not responsive to their name or favorite treat. If you notice abnormal or unusual behavior, your pig needs to be seen by a vet.

A grand mal seizure is what most people think of when talking about seizures. This is the dramatic kind, where the victim collapses and jerks uncontrollably, and can last for several minutes. Petit mal seizures are short, and are often described as a moment or two of being frozen. You will need to differentiate between seizure activity and normal pig behavior. Terrified pigs can "freeze" into "invisible pigs". Predators are attracted to movement. By standing perfectly still and "frozen", a wild pig can evade a predator and stay safe. Because their life might depend on it, a frightened pig can stay "invisible" for many minutes.

There has always been the thinking in human medicine that vaccinations have been the cause of seizures. I am not a vet, so I can't speak to any relation between vaccines and seizures in pigs; although I would assume that it is at least somewhat similar to humans. I do know that vaccines do not cause epilepsy, but sometimes someone who has epilepsy will experience a seizure, occasionally it will be their first seizure they have ever experienced, within a couple days of certain vaccines as something in the vaccine triggers the same sodium channels in the brain that get triggered during tonic/clonic activity. So a vaccine can trigger the seizure activity, but the underlying disorder/condition already has to exist for that to happen. The vaccination doesn't cause the seizure, the underlying neurological issue causes the seizure. (This is in my experience-BS)

Often times there is a genetic predisposition to the seizure disorder. In general, when pigs are “selected for smaller size,” in addition to nutritional stunting, many other possible problems of miniature pigs may be magnified. These include hypoglycemia, idiopathic seizures, musculoskeletal deformities, heart disease, cleft palate, atresia ani, and reproductive problems such as dystocia and agalactia.

Above information edited by Brittany Sawyer to add key points to the article. 2015

http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/exotic

http://www.thepigsite.com/diseaseinfo/hypoglycaemia/

Some potbellied pigs develop seizures of unknown cause. Pigs less than 1 year old are most likely to have such seizures. The frequency of these seizures varies greatly. A pig may have only 1 or 2 a month or as many as several each day. Pigs with only a few seizures may require no special medication. Animals with frequent seizures may be placed on medication to control the episodes. Some affected pigs may stop having seizures as they get older. http://www.merckvetmanual.com

Several bacterial or viral infections have been found to cause a high fever and in turn the high fever causes seizures. Controlling the fever and/or eliminating the underlying cause with antivirals or antibiotics is important to stopping the seizure activity. There is usually a trigger for seizures though. At times it can be something as small as a smell.

There are times when another illness is causing the seizures such as this "bloat induced seizure" article.

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/33277

Normal treatment for seizure activity will be to control the seizures, usually with an anti-convulsant, IV fluids, and oxygen. The underlying cause will be determined and corrected as well.

Study conducted regarding pigs having seizures:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8313711

A seizure is any sudden and uncontrolled movement of the animal's body caused by abnormal brain activity. Seizures may be very severe and affect all of the body, or quite mild, affecting only a portion of the pet. The pet may or may not seem conscious or responsive, and may urinate or have a bowel movement.

Seizure activity that lasts longer than 3 to 5 minutes can cause severe side effects, such as fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) or brain (cerebral edema). A dramatic rise in body temperature (hyperthermia) can also result, causing internal organ damage.

Seizures can be caused by epilepsy, toxins, low blood sugar, brain tumors and a host of other medical conditions. Your veterinarian can help you determine the cause of seizures in your pet, and if necessary can refer you to a specialist to help with the diagnosis or treatment of seizures. In general, animals less than one year of age typically have seizures due to a birth defect such as hydrocephalus (water on the brain) or a liver defect called a portosystemic shunt (among others). Animals that have their first seizure between 1 and 5 years of age typically suffer from epilepsy, while those over 5 years of age often have another medical condition causing the seizures such as a brain tumor, stroke or low blood sugar. This isn't necessarily the case for mini pigs though, they can have seizure disorders at any time with an unknown cause. These are general guidelines, however, and they may or may not apply to your pig.

All pigs that have a seizure should have lab tests to help diagnose the underlying cause, and make sure their organs can tolerate any medications that may be needed to control seizures. Once underlying diseases are ruled out by your veterinarian, some pets require medications such as phenobarbital or potassium bromide, among others, to control seizures. These medications may require frequent dose adjustments and monitoring of blood levels, so it is best to have an open and honest discussion with your veterinarian about the effort and costs involved in treating your pig for seizures.

Because the diagnostic testing isn't typically done on pigs as it is on humans, often times, it's difficult to pinpoint the cause unless your pig is diagnosed with an illness or disease with a known history of causing seizures. A dietary change or accidental ingestion of sodium rich food without access to fresh water can lead to seizures. Water deprivation also sometimes called "salt toxicity" is the usual cause for that particular situation. There are some pigs that may have some kind of genetic or congenital defect within the brain that causes seizures. There have been cases when other medical issues are compounded and complicated resulting in seizures or contributing to seizure activity. There are febrile seizures that are seizures caused by having a high fever. Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) has been known to cause seizures in mini pigs as well, especially piglets who aren't able to mobilize the low glycogen reserves stored in the liver to provide the rest of the body with adequate levels of glucose in the blood. Therefore, it is especially important that piglet stays with mom so he/she is able to nurse and receive the appropriate amounts of lactose from mother’s milk. If a piglet cannot obtain sufficient lactose to maintain its energy output, it runs out of energy, its body temperature drops and ultimately it goes into a coma and dies. If your pig is actively seizing, your pig needs to be seen by a vet.

Keep a journal of when the seizures are occurring, what your pig was doing beforehand, foods your pig has eaten and anything else pertinent. Vaccinations within the last 30 days, parasite medication or any other medication including supplements within the last 30 days, exposure to any toxic substances, anything that may be related to why your pig is having seizures would be helpful to your vet who will be trying to determine the cause. Seizure activity can happen in pigs for the same reason it happens in dogs and cats -- and idiopathic epilepsy is common in the smaller breeds of pigs. If blood work is normal, sodium is low, then generally pigs will be treated for meningitis (also common in small breeds of pigs) with an antibiotic and an anti inflammatory, and then start these pigs on phenobarbital and, in some cases, KBr (Potassium Bromide).

There are also a few different types of seizures that a pig can have. You may see the classic inability to control bodily function seizure. You also have seizures that aren't as visibly noticeable and consists of the pig just staring off into space, looking as if they were in a trance or not responsive to their name or favorite treat. If you notice abnormal or unusual behavior, your pig needs to be seen by a vet.

A grand mal seizure is what most people think of when talking about seizures. This is the dramatic kind, where the victim collapses and jerks uncontrollably, and can last for several minutes. Petit mal seizures are short, and are often described as a moment or two of being frozen. You will need to differentiate between seizure activity and normal pig behavior. Terrified pigs can "freeze" into "invisible pigs". Predators are attracted to movement. By standing perfectly still and "frozen", a wild pig can evade a predator and stay safe. Because their life might depend on it, a frightened pig can stay "invisible" for many minutes.

There has always been the thinking in human medicine that vaccinations have been the cause of seizures. I am not a vet, so I can't speak to any relation between vaccines and seizures in pigs; although I would assume that it is at least somewhat similar to humans. I do know that vaccines do not cause epilepsy, but sometimes someone who has epilepsy will experience a seizure, occasionally it will be their first seizure they have ever experienced, within a couple days of certain vaccines as something in the vaccine triggers the same sodium channels in the brain that get triggered during tonic/clonic activity. So a vaccine can trigger the seizure activity, but the underlying disorder/condition already has to exist for that to happen. The vaccination doesn't cause the seizure, the underlying neurological issue causes the seizure. (This is in my experience-BS)

Often times there is a genetic predisposition to the seizure disorder. In general, when pigs are “selected for smaller size,” in addition to nutritional stunting, many other possible problems of miniature pigs may be magnified. These include hypoglycemia, idiopathic seizures, musculoskeletal deformities, heart disease, cleft palate, atresia ani, and reproductive problems such as dystocia and agalactia.

Above information edited by Brittany Sawyer to add key points to the article. 2015

http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/exotic

http://www.thepigsite.com/diseaseinfo/hypoglycaemia/

Some potbellied pigs develop seizures of unknown cause. Pigs less than 1 year old are most likely to have such seizures. The frequency of these seizures varies greatly. A pig may have only 1 or 2 a month or as many as several each day. Pigs with only a few seizures may require no special medication. Animals with frequent seizures may be placed on medication to control the episodes. Some affected pigs may stop having seizures as they get older. http://www.merckvetmanual.com

Several bacterial or viral infections have been found to cause a high fever and in turn the high fever causes seizures. Controlling the fever and/or eliminating the underlying cause with antivirals or antibiotics is important to stopping the seizure activity. There is usually a trigger for seizures though. At times it can be something as small as a smell.

There are times when another illness is causing the seizures such as this "bloat induced seizure" article.

https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/33277

Normal treatment for seizure activity will be to control the seizures, usually with an anti-convulsant, IV fluids, and oxygen. The underlying cause will be determined and corrected as well.

Study conducted regarding pigs having seizures:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8313711

What to Do

- Protect the pig from injuring herself during or after the seizure. Keep her from falling from a height (block off stairs, if applicable) and especially keep away from water.

- Remove other pets from the area as some pets become aggressive after a seizure.

- Protect yourself from being bitten.

- Record the time the seizure begins and ends, and if it started with a certain body part (such as twitching of an eye).

- Record what was happening before the seizure and what happens afterwards, note the times of these occurences.

- If the seizure or convulsion lasts over 3 minutes, cool the pig with cool (not cold) water on the ears, belly and feet, and seek veterinary attention at once.

- If your pig has two or more seizures in a 24-hour period, seek veterinary attention.

- If your pig has one seizure that is less than 3 minutes and seems to recover completely, contact your veterinarian’s office for further instructions. A visit may or may not be recommended based on your pig’s medical history.

- If the pig loses consciousness and is not breathing, begin CPR. Click here to learn how to do CPR on a mini pig.

- Do not place your hands near the pig's mouth. (They do not swallow their tongues.) You risk being bitten.

- Do not slap, throw water on, or otherwise try to startle your pig out of a seizure. The seizure will end when it ends, and you cannot affect it by slapping, yelling, or any other action.

Seizures

by Cathy Zolicani, DVM

Seizures are very common in pigs. Seizures are not a disease in and of themselves. They are symptoms of an underlying condition that manifests through seizures (like sneezing can be a symptom of many things – some serious like a nasal tumor, some not at all serious like pepper up the nose). Some underlying causes include: genetics (its in the DNA), malnutrition, head/brain trauma (some is not obvious – for example, oxygen deprivation in the birth canal causes brain trauma. And how would you know? Metabolic disease like liver shunts or diabetes (blood glucose fluctuations), parasites, toxins, organ dysfunction, hormonal imbalances, heart disease. Some of these are very significant because they can result in the death of the pig. Some of these are not life-threatening and simply need to be managed. In 75% of the cases, we never find the underlying cause of the seizure – we call these pigs epileptics.

Basic work up to find the cause of seizures includes blood work, xrays of chest and abdomen. Additional diagnostics, like MRI’s or CT scans can be done. Many anticonvulsant medications are available for pigs, and they work very well. All medications, however, have other effects in the body and we do not usually treat the seizures unless they become very severe, very frequent, or place pig or owner in tremendous distress. It can be difficult to find the optimal dose in any individual, so we have to titrate the dose to find just the right level to control the seizures and minimize size effects. It can take up to 6 months to fully regulate a pig and find the best dose.

So, when do you have an emergency? The first seizure is always an emergency. After that, any time there are 6 seizures in a 24 hour period, 3 in a single hour, or if the violent part of the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes (time it). The seizure itself is not fatal, but the underlying cause can be. Also, if a pig gets locked into a violent seizure, his body temperature can rise to 110 or higher, causing malignant hyperthermia and death. If any of these occur, you should seek a vet right away.

What do do when your pig has a seizure? Time it. Keep a calendar of seizures so you can tell how frequent they are. Record what the pig is doing before the seizure – this may be a trigger to cause the seizure, and if you eliminate the behavior, you may be able to stop the seizure without medications.

Never hold you pig on its back like a baby – it cannot control its swallowing and breathing muscles and may aspirate saliva. Pigs may salivate, defecate and urinate while having a seizure. They cannot help it. Lay your pig on its side so the saliva can run out of its mouth rather than down its throat. If you must transport during a seizure, keep the pig on its side and keep the mouth down. You can place it in the bottom of a kennel or on a blanket to use as a gurney to keep it on its side.

Seizures have 3 phases – each lasting as little as 3 seconds, some lasting up to 3 days. A pre-seizure phase called pre-ictal phase. The pig knows it is coming and has strange behavior. You may notice this and may be able to prevent a seizure by adjusting medication. The seizure (ictal phase) – convulsions of various severity will occur. The post-ictal phase – think of it like rebooting the brain computer. It can take 3 sec or 3 days – pigs will be sleepy, they may act blind, they may not respond to stimuli easily. It is best to leave them mostly alone during this phase, but have them in a quiet safe place.

Written by Cathy Zolicani, DVM

by Cathy Zolicani, DVM

Seizures are very common in pigs. Seizures are not a disease in and of themselves. They are symptoms of an underlying condition that manifests through seizures (like sneezing can be a symptom of many things – some serious like a nasal tumor, some not at all serious like pepper up the nose). Some underlying causes include: genetics (its in the DNA), malnutrition, head/brain trauma (some is not obvious – for example, oxygen deprivation in the birth canal causes brain trauma. And how would you know? Metabolic disease like liver shunts or diabetes (blood glucose fluctuations), parasites, toxins, organ dysfunction, hormonal imbalances, heart disease. Some of these are very significant because they can result in the death of the pig. Some of these are not life-threatening and simply need to be managed. In 75% of the cases, we never find the underlying cause of the seizure – we call these pigs epileptics.

Basic work up to find the cause of seizures includes blood work, xrays of chest and abdomen. Additional diagnostics, like MRI’s or CT scans can be done. Many anticonvulsant medications are available for pigs, and they work very well. All medications, however, have other effects in the body and we do not usually treat the seizures unless they become very severe, very frequent, or place pig or owner in tremendous distress. It can be difficult to find the optimal dose in any individual, so we have to titrate the dose to find just the right level to control the seizures and minimize size effects. It can take up to 6 months to fully regulate a pig and find the best dose.

So, when do you have an emergency? The first seizure is always an emergency. After that, any time there are 6 seizures in a 24 hour period, 3 in a single hour, or if the violent part of the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes (time it). The seizure itself is not fatal, but the underlying cause can be. Also, if a pig gets locked into a violent seizure, his body temperature can rise to 110 or higher, causing malignant hyperthermia and death. If any of these occur, you should seek a vet right away.

What do do when your pig has a seizure? Time it. Keep a calendar of seizures so you can tell how frequent they are. Record what the pig is doing before the seizure – this may be a trigger to cause the seizure, and if you eliminate the behavior, you may be able to stop the seizure without medications.

Never hold you pig on its back like a baby – it cannot control its swallowing and breathing muscles and may aspirate saliva. Pigs may salivate, defecate and urinate while having a seizure. They cannot help it. Lay your pig on its side so the saliva can run out of its mouth rather than down its throat. If you must transport during a seizure, keep the pig on its side and keep the mouth down. You can place it in the bottom of a kennel or on a blanket to use as a gurney to keep it on its side.

Seizures have 3 phases – each lasting as little as 3 seconds, some lasting up to 3 days. A pre-seizure phase called pre-ictal phase. The pig knows it is coming and has strange behavior. You may notice this and may be able to prevent a seizure by adjusting medication. The seizure (ictal phase) – convulsions of various severity will occur. The post-ictal phase – think of it like rebooting the brain computer. It can take 3 sec or 3 days – pigs will be sleepy, they may act blind, they may not respond to stimuli easily. It is best to leave them mostly alone during this phase, but have them in a quiet safe place.

Written by Cathy Zolicani, DVM

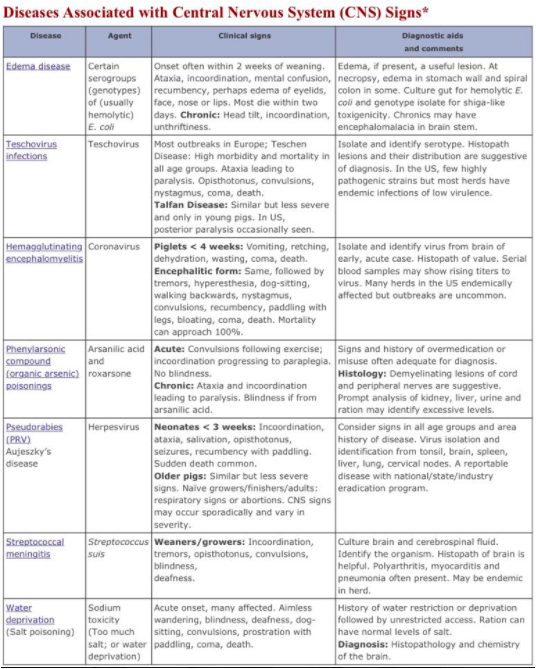

Phenylarsonic (Organic Arsenical)

PoisoningRoxarsone and arsanilic acid are used to promote growth and to treat swine dysentery and eperythrozoonosis. Roxarsone is more toxic than arsanilic acid but most features of poisoning are similar in both cases. Poisoning is dose-related. Chronic poisoning may occur when low doses are given over a long period of time. Acute poisoning occurs when large amounts are consumed in a short period of time.

Signs of chronic poisoning with arsanilic acid include goose-stepping, hind limb ataxia, limb paresis, and blindness. Blindness is not typical of poisoning with other organic arsenicals. Paralyzed pigs remain alert. If provided with feed and water, they will continue to eat and drink. There are few or no associated gross lesions. Signs of acute poisoning include cutaneous erythema, ataxia, vestibular disturbances, and terminal muscular weakness. An acute gastroenteritis will often be present in these cases. Although signs and lesions of roxarsone poisoning will often be similar, an additional syndrome has been described that includes repeated convulsive seizures following exercise without the blindness produced by arsanilic acid. Microscopic lesions associated with chronic poisoning by these compounds include neuronal degeneration of optic and peripheral nerve trunks, including the sciatic nerves. Neuronal lesions may not be present in acute cases.

A tentative diagnosis can often be based on a history of misuse of the compounds and the presence of characteristic clinical signs in chronically affected swine. Diagnosis may be assisted by toxicologic assays of kidney, liver, muscle, and feed.

Prevention of organic arsenical poisoning can be achieved simply by correct management of these legal compounds during feed preparation or medication. In particular, water treated with these compounds should not be given to thirsty pigs, as they are likely to consume a toxic dose. Directions provided with the compounds should be followed carefully. The neurotoxic effect of poisoning sometimes is reversible if the compound is removed within two or three days of the appearance of signs. Blindness and long standing peripheral nerve damage may be permanent.

Edema Disease:

Onset of the disease usually is around two weeks postweaning. Onset often is signaled by finding a few thrifty pigs dead. Morbidity usually is low but mortality is high in pigs that show signs. Signs include anorexia, ataxia, stupor and recumbency often accompanied by paddling and running movements. When caught, affected pigs may respond with an abnormal squeal, a consequence of laryngeal edema. Diarrhea usually is not present in pigs with typical ED but may be present in other pigs in the same group. Swelling of the face and eyelids may or may not be present. Sick pigs die within a few hours or days. The few that survive often have neurologic deficits. The course of ED in a herd usually is around two weeks. However, the disease may reappear as other batches of pigs reach the age group at risk.

Treatment of pigs affected with ED can be frustrating since toxin production in the gut is quite advanced by the time clinical signs become visible. Affected pigs must be treated parenterally. Antimicrobials may be of some value in less severely-affected pigs. Supportive therapy to counteract acidosis and dehydration is valuable in early cases. During an outbreak, efforts are directed toward reducing the incidence of infection in the remainder of the population at risk. Administration of antimicrobials and acidifiers in the water may be helpful. In severe outbreaks, removing feed and replacement with a ration containing less protein, a lower percentage of soybean meal, or higher proportion of rolled oats is required.

No prevention method is universally accepted or successful because the erratic occurrence of ED makes intervention strategies hard to assess. Seven general strategies should be considered when formatting control strategies for affected farms.

Porcine Picornaviruses (Enteroviruses)

Definition: A diverse group of diseases are caused by closely related viruses in the family Picornaviradae; the virus family has recently been reorganized. Enterovirus was one of seven genera in the family under the former taxonomy and contained numerous virus species to which swine were known to be susceptible, with virus species further designated by a serotyping scheme. Around 2000, the taxonomy was revised based on genomic sequence data. Currently, porcine enterovirus 1 (PEV 1, the prototype “Teschen virus” and “Talfan virus”), PEV 2 through 7, and PEV 11-13 have been moved to a new genus called Teschovirus. Porcine enteroviruses 8-10 remain in the original Enterovirus genus. Diseases manifested by the different viruses vary widely and include polioencephalomyelitis, female reproductive failure, myocarditis, pericarditis, pneumonia, and diarrhea.

Occurrence: Porcine picornaviruses are ubiquitous. They occur only in swine and most infections are asymptomatic. Teschen disease, the most virulent picornaviral infection, causes polioencephalomyelitis (PEM). The disease occurs only in central Europe and parts of Africa. Talfan disease, a similar but less severe disease, causes PEM in Europe, North America and Australia. Outbreaks in North America have occurred infrequently and been of minor significance.

Epidemiology: All picornaviruses are assumed to have similar epidemiology. Less virulent strains of virus are endemic in most herds. The viruses are shed in the feces and transmission usually is fecal-oral. Spread of virus usually is by direct or indirect contact with infected pigs. Infected fetuses born alive sometimes are a source of viral exposure of other pigs. Fomites can carry the relatively stable viruses. All ages of swine are susceptible if they have not previously encountered a picornavirus of that serogroup.

Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis (Vomiting and Wasting Disease)

Definition: A disease seen in pigs less than four weeks old, characterized by signs that include vomiting, wasting and, perhaps, neurologic signs.

Occurrence: Hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis (HE) occurs only in swine. The disease occurs in most major swine-raising countries but tends to be quite sporadic. Infection is clinically silent except in piglets less than four weeks old. In these, the disease occurs as an acute outbreak affecting most piglets in litters of nonimmune dam.

Clinical signs: Vomiting and wasting syndrome: Sneezing and coughing may occur at onset. Within a few days, vomiting of milk and retching are prominent signs. The young pigs dehydrate rapidly and often grind their teeth. When water is supplied, piglets mouth it but drink little, presumably because of pharyngeal paralysis. After a few days they exhibit dyspnea, cyanosis, coma and die.

Pigs in older litters survive longer but continue to vomit occasionally. The anterior abdomen of some of them may become distended, presumably from impaired emptying and accumulation of gas. Most affected piglets waste away over a few weeks and die. The few that survive remain unthrifty. Morbidity and mortality in both syndromes approaches 100% in affected litters.

Encephalomyelitis syndrome: Initial signs are similar to those in the above syndrome. Vomiting and retching occur less often and lead to less dehydration. In one to three days, any of a variety of signs of encephalomyelitis appear. These may include: stilted gait, muscle tremors, nystagmus, blindness, opisthotonus, convulsions, and progressive paresis leading to recumbency with paddling of the legs. Occasional pigs walk backwards and assume a dog-sitting position. Affected pigs soon weaken, pass into coma and die. In some litters of older pigs, there may be only transient posterior paresis followed by recovery.

Pseudorabies - PRV

Definition: Pseudorabies (PRV) is a major viral disease manifested in swine by signs and lesions that vary among different age groups. The disease is characterized by three overlapping syndromes that reflect lesions in the central nervous system (CNS), respiratory system or reproductive system.

Occurrence: Among domestic animals, swine are the only natural host of pseudorabies virus (PRV). All age groups not previously exposed or vaccinated are susceptible. The disease was eradicated from the US commercial pig industry in 2004 but remains in some localized feral swine populations. The disease remains common in many other major swine-raising countries. Most domestic animals (cattle, sheep, dogs, cats, and goats but not horses) and many wild animals (rats, mice, raccoons, opossums, rabbits, and several fur-bearing mammals) are susceptible to the virus but transmission only occurs when these species are kept in close contact with acutely infected swine; death is the usual outcome in these aberrant hosts. Pseudorabies occurs with some frequency in both cattle and sheep, especially those in close contact with swine. There is no evidence that PRV is a health threat to humans.

Streptococcal Infections

The predominant streptococcal disease of swine is caused by Streptococcus suis. Other less common, largely sporadic, streptococcal infections are summarized as follows.

Sporadic infections occasionally are caused by Streptococcus equisimilis. This beta-hemolytic streptococcus and a few others sometimes cause arthritis, septicemia or meningitis in young pigs, complicate other disease processes, or may contribute to cases of vegetative, valvular endocarditis in older production pigs. This organism is indigenous in the vagina and infects piglets at birth. The cases in young pigs are a result of navel infection or from breaks in the integument as a result of knee abrasions, or infection of skin wounds including those caused by tail docking, ear notching or clipping of needle teeth.

Streptococcus porcinus is the same as Lancefield group E streptococci associated with jowl abscess (feeder boils) in swine. This disease was once quite prevalent but is now rare, presumably because of improvements in husbandry and feeder design. It is occasionally isolated from pigs with septicemia or abscesses.

Additional streptococci believed to be pathogens have been isolated from the respiratory tract, mammary glands, localized skin lesions and subcutaneous abscesses, from the reproductive tract of aborting sows, and sows with fertility problems or agalactia. Their role in these conditions is less clear. Streptococcus durans has been associated with enteritis in suckling pigs.

Clinical signs: Signs and lesions are similar in all S. suis infections, regardless of serotype. Signs usually suggest septicemia and/or localization of systemic infection. Pigs with septicemia die after a short, acute course and may not have been observed as sick pigs. Young piglets with central nervous system (CNS) lesions are often found in lateral recumbency and paddling. Older pigs have a wider variety of CNS type signs that include ataxia, opisthotonus, incoordination, tremors, convulsions, blindness and deafness. Pigs with polyarthritis have swollen joints and are lame. In some outbreaks, respiratory signs associated with pneumonia may occur. Both morbidity and mortality vary widely and are affected by treatment. Streptococcus suis, much like Pasteurella multocida, is ubiquitous in swine and a frequent secondary contributor to pneumonia.

Otitis interna in swine and other animals is generally believed to be a complication of otitis media. By contrast, the route of infection to the ear in humans is often from the brain in the presence of meningitis. Hearing loss in humans due to meningogenic labyrinthitis is a common sequela to bacterial meningitis. Meningitis is an important condition in swine, and Streptococcus Suis is a primary causative agent.

http://vet.sagepub.com/strepsuisinfection/full.pdf

Exudative labyrinthitis was detected in a majority (20 out of 28 subjects) of the pigs with meningitis in the above linked article. The inflammatory changes in the central nervous system and meninges were as previously described for bacterial meningitis due to pyogenic bacteria. The character of the inner ear lesions was compatible with that reported in previous studies of pigs and with descriptions from human studies.

Salt Poisoning (Water Deprivation; Sodium Ion Toxicosis)

Salt poisoning can occur in pigs either as a consequence of water deprivation or from sudden ingestion of too much salt. Click here to read more in depth information regarding water deprivation/salt toxicity.

Poisoning in water-deprived pigs can occur in pigs consuming a proper level of salt but it is more likely if the salt level in the feed is excessive. Signs often are precipitated, or worsened, by allowing the pigs sudden, unlimited access to water. Water deprivation can occur for many reasons but commonly may be the result of freezing of the water source, plugged water nipples, or inadvertently leaving a water valve closed. Operators may not always be forthright in admitting human errors related to water deprivation. Poisoning has occurred following prolonged shipping without access to water, followed by unlimited access.

Following sudden heavy rains, salt poisoning can occur in swine after ingestion of salty brine from overflowing, loose-salt boxes provided for other livestock and is also reported following ingestion of whey. This type of poisoning is more likely in water-deprived pigs.

Clinical signs of sodium ion toxicosis are caused by the acute cerebral edema that occurs as a result of multiple central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Because the condition most often occurs secondary to water deprivation (rather than a primary toxic intake of salt), salt poisoning is frequently apparent at a “pen” or “herd” level. Signs include aimless wandering, blindness, deafness and head pressing. Affected pigs sometimes “dog-sit”, slowly raise their nose upward and backward, and fall on their side in spasms that may be followed by paddling of the legs. They then may arise and continue their wandering.

Diagnosis associated with water deprivation may be suggested by history, signs, and elevated sodium levels in serum or cerebrospinal fluid. Gross lesions may be absent or limited to gastroenteritis. Gastroenteritis is more likely in pigs consuming salty brine and may be accompanied by diarrhea. A valuable but not infallible diagnostic aid is the microscopic observation of rather unique meningeal and cerebral perivascular cuffing by eosinophils in brain. Later and less reliably there may be laminar subcortical polioencephalomalacia or necrosis. Salt poisoning must be differentiated from all other encephalitic diseases. In an affected pen, a clue to the occurrence of water deprivation will be the absence of any urine or wet feces on the pen floor.

Water-deprived or affected pigs should be reintroduced to water slowly, given only small amounts of water at frequent intervals. This may suppress mortality. Pigs showing clinical signs usually die regardless of treatment.

Cerebral Parasites

The brain and its investing membranes are often infested with a species of entozoa, termed coenurus. They consist of a parental sac, pr membranous tunic, from which, externally, germination takes place. This mode of multiplication of this group of parasites differs from that which is observed in the hydatid (fluke), in which it occurs internally.

Cysticercosis: The larval form of Taenia solium, T. saginata, T. crassiceps, T. ovis, T. taeniaeformis or T. hydatigena is called a cysticercus. Cysticerci are fluid-filled vesicles that contain a single inverted protoscolex. In tissues other than the eye, the verebral ventricles or the subarachnoid space of the brain, this cyst is surrounded by a capsule of fibrous tissue Cysticerci are usually oblong and approximately 1 cm or less in diameter, but T. solium cysticerci can grow up to 10-15 cm in areas such as the subarachnoid space of the brain. A host may have one to hundreds of cysts.

A proliferating form, called racemose cysticercosis, is occasionally seen. This larva, which occurs mainly at the base of the brain, consists of a grape-like mass containing several connected bladders of various sizes. The protoscolex, if any, is usually dead. It is uncertain whether racemose cysticercosis is an aberrant T. solium cysticercus, the cysticercus of another species, or a sterile coenurus.

Cysticerci may be found almost anywhere, but each species has a predilection for certain tissues. In pigs, T. solium cysticerci are found mainly in the skeletal or cardiac muscles, liver, heart and brain. In humans, this species is most often found in the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, eyes and brain. Serious disease is almost always caused by cysticerci in the CNS (neurocysticercosis) or heart. T. hydatigena cysticerci are usually found in the abdominal cavity. They are generally attached to the omentum, mesentery and occasionally the surface of the liver. The migrating larvae leave hemorrhagic tracks in the liver that later become green/brown and finally, white and fibrotic. Some small cysticerci may also be found in the liver parenchyma, just below the capsule. They tend to degenerate and calcify early. In cattle and pigs, these lesions may resemble tuberculosis. More severe disease, including acute meningoencephalitis, convulsions and death can occur with large numbers of parasites.

Species specific information regarding pigs and how they can be infected:

Taenia asiatica

Clinical signs are uncommon in pigs infected with T. solium. T. solium can occasionally cause hypersensitivity of the snout, paralysis of the tongue, seizures, fever and muscle stiffness in pigs. Deaths have been reported as the result of myocarditis during experimental infections.

Mortality: The prevalence of infection varies with the parasite. In some parts of the world, up to 43% of the pigs have antibodies to T. solium. Free-roaming pigs have a much greater risk of infection than pigs that are confined to pens. T. solium and T. saginata are both uncommon in livestock in the U.S. T. multiceps infection (gid) can be a common and important disease in some countries or regions, such as parts of the United Kingdom.

Epilepsy

Primary or idiopathic epilepsy is the major cause of recurrent seizures in animals between 1 and 5 years of age. Since no obvious evidence of brain injury is found in primary epilepsy, the probable cause of seizures may be related to a pre-existing or hereditary chemical or functional defect in the brain. The typical seizure due to primary epilepsy is a one to two minute generalized convulsion characterized by collapse, stiffening and/or paddling of the limbs, jaw-chomping, salivation, occasional loss of urine and/or feces, and unconsciousness (no response to calling, touching, etc.). Bear in mind, however, that primary epilepsy may be milder in nature and that not all of the above signs may be seen. A seizure event is typically followed by a "post-ictal" or post-seizure period characterized by incoordination, exhaustion, and disorientation. This period may last for minutes or hours and should not be confused with the actual seizure.

Sources:

http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/pdfs/taenia

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam

https://vet.osu.edu/vmc/neurology-and-neurosurgery/epilepsy

PoisoningRoxarsone and arsanilic acid are used to promote growth and to treat swine dysentery and eperythrozoonosis. Roxarsone is more toxic than arsanilic acid but most features of poisoning are similar in both cases. Poisoning is dose-related. Chronic poisoning may occur when low doses are given over a long period of time. Acute poisoning occurs when large amounts are consumed in a short period of time.

Signs of chronic poisoning with arsanilic acid include goose-stepping, hind limb ataxia, limb paresis, and blindness. Blindness is not typical of poisoning with other organic arsenicals. Paralyzed pigs remain alert. If provided with feed and water, they will continue to eat and drink. There are few or no associated gross lesions. Signs of acute poisoning include cutaneous erythema, ataxia, vestibular disturbances, and terminal muscular weakness. An acute gastroenteritis will often be present in these cases. Although signs and lesions of roxarsone poisoning will often be similar, an additional syndrome has been described that includes repeated convulsive seizures following exercise without the blindness produced by arsanilic acid. Microscopic lesions associated with chronic poisoning by these compounds include neuronal degeneration of optic and peripheral nerve trunks, including the sciatic nerves. Neuronal lesions may not be present in acute cases.

A tentative diagnosis can often be based on a history of misuse of the compounds and the presence of characteristic clinical signs in chronically affected swine. Diagnosis may be assisted by toxicologic assays of kidney, liver, muscle, and feed.

Prevention of organic arsenical poisoning can be achieved simply by correct management of these legal compounds during feed preparation or medication. In particular, water treated with these compounds should not be given to thirsty pigs, as they are likely to consume a toxic dose. Directions provided with the compounds should be followed carefully. The neurotoxic effect of poisoning sometimes is reversible if the compound is removed within two or three days of the appearance of signs. Blindness and long standing peripheral nerve damage may be permanent.

Edema Disease:

Onset of the disease usually is around two weeks postweaning. Onset often is signaled by finding a few thrifty pigs dead. Morbidity usually is low but mortality is high in pigs that show signs. Signs include anorexia, ataxia, stupor and recumbency often accompanied by paddling and running movements. When caught, affected pigs may respond with an abnormal squeal, a consequence of laryngeal edema. Diarrhea usually is not present in pigs with typical ED but may be present in other pigs in the same group. Swelling of the face and eyelids may or may not be present. Sick pigs die within a few hours or days. The few that survive often have neurologic deficits. The course of ED in a herd usually is around two weeks. However, the disease may reappear as other batches of pigs reach the age group at risk.

Treatment of pigs affected with ED can be frustrating since toxin production in the gut is quite advanced by the time clinical signs become visible. Affected pigs must be treated parenterally. Antimicrobials may be of some value in less severely-affected pigs. Supportive therapy to counteract acidosis and dehydration is valuable in early cases. During an outbreak, efforts are directed toward reducing the incidence of infection in the remainder of the population at risk. Administration of antimicrobials and acidifiers in the water may be helpful. In severe outbreaks, removing feed and replacement with a ration containing less protein, a lower percentage of soybean meal, or higher proportion of rolled oats is required.

No prevention method is universally accepted or successful because the erratic occurrence of ED makes intervention strategies hard to assess. Seven general strategies should be considered when formatting control strategies for affected farms.

- Management factors include minimizing environmental stresses (e.g. temperature variation, drafts, damp conditions), limited commingling, and using all in/all out (AIAO) system with scrupulous sanitation.

- Nutritional considerations include creep feeding, restricted feeding, multiple feedings (small quantities 3-6 times/day) after weaning, adding oats (high in fiber) to the rations, acidifiers (organic or inorganic acids) added to feed or water, decreased protein in the ration, addition of zinc oxide (2500 ppm) to the ration, and addition of plasma protein.

- Antimicrobial intervention is often practiced. Various antibiotics have been added to rations or water but the efficacy is difficult to evaluate because outbreaks do not occur regularly; some affect only a few pigs, some pigs are naturally immune, and outbreaks end spontaneously. Antimicrobial resistance eventually dooms this strategy over the long term.

- Immunoprophylaxis can be successful by passive or active protection. Oral ingestion products (milk, plasma protein, egg powder) containing antibody can help to prevent colonization and disease. Disadvantages of passive protection are cost, lack of cross-protection between pilus or toxin types, and possibility of susceptibility remaining following cessation of feeding. Active immunity can be induced against specific adhesins or toxins. Oral vaccination with live or killed cultures that contain F18 or F4 (K88) pili but lacking genes for toxin production have been successful. Toxoids prepared from Stx2e have also been demonstrated effective against ED but are not commercially available. Whole-cell bacterins have been much less effective.

- Competitive exclusion, a process whereby receptors for E. coli are occupied by nonvirulent agents, is being investigated and may offer opportunity for control in the future.

- In herds negative for ED, it is prudent to prevent introduction by careful scrutiny of disease history of breeding stock. Eradication may be possible by using depopulation and disinfection.

- Natural resistance to ED is possible in pigs genetically lacking receptors for F18 and/or F4 (K88) pili. Genetically resistant pigs have been developed.

Porcine Picornaviruses (Enteroviruses)

Definition: A diverse group of diseases are caused by closely related viruses in the family Picornaviradae; the virus family has recently been reorganized. Enterovirus was one of seven genera in the family under the former taxonomy and contained numerous virus species to which swine were known to be susceptible, with virus species further designated by a serotyping scheme. Around 2000, the taxonomy was revised based on genomic sequence data. Currently, porcine enterovirus 1 (PEV 1, the prototype “Teschen virus” and “Talfan virus”), PEV 2 through 7, and PEV 11-13 have been moved to a new genus called Teschovirus. Porcine enteroviruses 8-10 remain in the original Enterovirus genus. Diseases manifested by the different viruses vary widely and include polioencephalomyelitis, female reproductive failure, myocarditis, pericarditis, pneumonia, and diarrhea.

Occurrence: Porcine picornaviruses are ubiquitous. They occur only in swine and most infections are asymptomatic. Teschen disease, the most virulent picornaviral infection, causes polioencephalomyelitis (PEM). The disease occurs only in central Europe and parts of Africa. Talfan disease, a similar but less severe disease, causes PEM in Europe, North America and Australia. Outbreaks in North America have occurred infrequently and been of minor significance.

Epidemiology: All picornaviruses are assumed to have similar epidemiology. Less virulent strains of virus are endemic in most herds. The viruses are shed in the feces and transmission usually is fecal-oral. Spread of virus usually is by direct or indirect contact with infected pigs. Infected fetuses born alive sometimes are a source of viral exposure of other pigs. Fomites can carry the relatively stable viruses. All ages of swine are susceptible if they have not previously encountered a picornavirus of that serogroup.

Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis (Vomiting and Wasting Disease)

Definition: A disease seen in pigs less than four weeks old, characterized by signs that include vomiting, wasting and, perhaps, neurologic signs.

Occurrence: Hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis (HE) occurs only in swine. The disease occurs in most major swine-raising countries but tends to be quite sporadic. Infection is clinically silent except in piglets less than four weeks old. In these, the disease occurs as an acute outbreak affecting most piglets in litters of nonimmune dam.

Clinical signs: Vomiting and wasting syndrome: Sneezing and coughing may occur at onset. Within a few days, vomiting of milk and retching are prominent signs. The young pigs dehydrate rapidly and often grind their teeth. When water is supplied, piglets mouth it but drink little, presumably because of pharyngeal paralysis. After a few days they exhibit dyspnea, cyanosis, coma and die.

Pigs in older litters survive longer but continue to vomit occasionally. The anterior abdomen of some of them may become distended, presumably from impaired emptying and accumulation of gas. Most affected piglets waste away over a few weeks and die. The few that survive remain unthrifty. Morbidity and mortality in both syndromes approaches 100% in affected litters.

Encephalomyelitis syndrome: Initial signs are similar to those in the above syndrome. Vomiting and retching occur less often and lead to less dehydration. In one to three days, any of a variety of signs of encephalomyelitis appear. These may include: stilted gait, muscle tremors, nystagmus, blindness, opisthotonus, convulsions, and progressive paresis leading to recumbency with paddling of the legs. Occasional pigs walk backwards and assume a dog-sitting position. Affected pigs soon weaken, pass into coma and die. In some litters of older pigs, there may be only transient posterior paresis followed by recovery.

Pseudorabies - PRV

Definition: Pseudorabies (PRV) is a major viral disease manifested in swine by signs and lesions that vary among different age groups. The disease is characterized by three overlapping syndromes that reflect lesions in the central nervous system (CNS), respiratory system or reproductive system.

Occurrence: Among domestic animals, swine are the only natural host of pseudorabies virus (PRV). All age groups not previously exposed or vaccinated are susceptible. The disease was eradicated from the US commercial pig industry in 2004 but remains in some localized feral swine populations. The disease remains common in many other major swine-raising countries. Most domestic animals (cattle, sheep, dogs, cats, and goats but not horses) and many wild animals (rats, mice, raccoons, opossums, rabbits, and several fur-bearing mammals) are susceptible to the virus but transmission only occurs when these species are kept in close contact with acutely infected swine; death is the usual outcome in these aberrant hosts. Pseudorabies occurs with some frequency in both cattle and sheep, especially those in close contact with swine. There is no evidence that PRV is a health threat to humans.

Streptococcal Infections

The predominant streptococcal disease of swine is caused by Streptococcus suis. Other less common, largely sporadic, streptococcal infections are summarized as follows.

Sporadic infections occasionally are caused by Streptococcus equisimilis. This beta-hemolytic streptococcus and a few others sometimes cause arthritis, septicemia or meningitis in young pigs, complicate other disease processes, or may contribute to cases of vegetative, valvular endocarditis in older production pigs. This organism is indigenous in the vagina and infects piglets at birth. The cases in young pigs are a result of navel infection or from breaks in the integument as a result of knee abrasions, or infection of skin wounds including those caused by tail docking, ear notching or clipping of needle teeth.

Streptococcus porcinus is the same as Lancefield group E streptococci associated with jowl abscess (feeder boils) in swine. This disease was once quite prevalent but is now rare, presumably because of improvements in husbandry and feeder design. It is occasionally isolated from pigs with septicemia or abscesses.

Additional streptococci believed to be pathogens have been isolated from the respiratory tract, mammary glands, localized skin lesions and subcutaneous abscesses, from the reproductive tract of aborting sows, and sows with fertility problems or agalactia. Their role in these conditions is less clear. Streptococcus durans has been associated with enteritis in suckling pigs.

Clinical signs: Signs and lesions are similar in all S. suis infections, regardless of serotype. Signs usually suggest septicemia and/or localization of systemic infection. Pigs with septicemia die after a short, acute course and may not have been observed as sick pigs. Young piglets with central nervous system (CNS) lesions are often found in lateral recumbency and paddling. Older pigs have a wider variety of CNS type signs that include ataxia, opisthotonus, incoordination, tremors, convulsions, blindness and deafness. Pigs with polyarthritis have swollen joints and are lame. In some outbreaks, respiratory signs associated with pneumonia may occur. Both morbidity and mortality vary widely and are affected by treatment. Streptococcus suis, much like Pasteurella multocida, is ubiquitous in swine and a frequent secondary contributor to pneumonia.

Otitis interna in swine and other animals is generally believed to be a complication of otitis media. By contrast, the route of infection to the ear in humans is often from the brain in the presence of meningitis. Hearing loss in humans due to meningogenic labyrinthitis is a common sequela to bacterial meningitis. Meningitis is an important condition in swine, and Streptococcus Suis is a primary causative agent.

http://vet.sagepub.com/strepsuisinfection/full.pdf

Exudative labyrinthitis was detected in a majority (20 out of 28 subjects) of the pigs with meningitis in the above linked article. The inflammatory changes in the central nervous system and meninges were as previously described for bacterial meningitis due to pyogenic bacteria. The character of the inner ear lesions was compatible with that reported in previous studies of pigs and with descriptions from human studies.

Salt Poisoning (Water Deprivation; Sodium Ion Toxicosis)

Salt poisoning can occur in pigs either as a consequence of water deprivation or from sudden ingestion of too much salt. Click here to read more in depth information regarding water deprivation/salt toxicity.

Poisoning in water-deprived pigs can occur in pigs consuming a proper level of salt but it is more likely if the salt level in the feed is excessive. Signs often are precipitated, or worsened, by allowing the pigs sudden, unlimited access to water. Water deprivation can occur for many reasons but commonly may be the result of freezing of the water source, plugged water nipples, or inadvertently leaving a water valve closed. Operators may not always be forthright in admitting human errors related to water deprivation. Poisoning has occurred following prolonged shipping without access to water, followed by unlimited access.

Following sudden heavy rains, salt poisoning can occur in swine after ingestion of salty brine from overflowing, loose-salt boxes provided for other livestock and is also reported following ingestion of whey. This type of poisoning is more likely in water-deprived pigs.

Clinical signs of sodium ion toxicosis are caused by the acute cerebral edema that occurs as a result of multiple central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Because the condition most often occurs secondary to water deprivation (rather than a primary toxic intake of salt), salt poisoning is frequently apparent at a “pen” or “herd” level. Signs include aimless wandering, blindness, deafness and head pressing. Affected pigs sometimes “dog-sit”, slowly raise their nose upward and backward, and fall on their side in spasms that may be followed by paddling of the legs. They then may arise and continue their wandering.

Diagnosis associated with water deprivation may be suggested by history, signs, and elevated sodium levels in serum or cerebrospinal fluid. Gross lesions may be absent or limited to gastroenteritis. Gastroenteritis is more likely in pigs consuming salty brine and may be accompanied by diarrhea. A valuable but not infallible diagnostic aid is the microscopic observation of rather unique meningeal and cerebral perivascular cuffing by eosinophils in brain. Later and less reliably there may be laminar subcortical polioencephalomalacia or necrosis. Salt poisoning must be differentiated from all other encephalitic diseases. In an affected pen, a clue to the occurrence of water deprivation will be the absence of any urine or wet feces on the pen floor.

Water-deprived or affected pigs should be reintroduced to water slowly, given only small amounts of water at frequent intervals. This may suppress mortality. Pigs showing clinical signs usually die regardless of treatment.

Cerebral Parasites

The brain and its investing membranes are often infested with a species of entozoa, termed coenurus. They consist of a parental sac, pr membranous tunic, from which, externally, germination takes place. This mode of multiplication of this group of parasites differs from that which is observed in the hydatid (fluke), in which it occurs internally.

Cysticercosis: The larval form of Taenia solium, T. saginata, T. crassiceps, T. ovis, T. taeniaeformis or T. hydatigena is called a cysticercus. Cysticerci are fluid-filled vesicles that contain a single inverted protoscolex. In tissues other than the eye, the verebral ventricles or the subarachnoid space of the brain, this cyst is surrounded by a capsule of fibrous tissue Cysticerci are usually oblong and approximately 1 cm or less in diameter, but T. solium cysticerci can grow up to 10-15 cm in areas such as the subarachnoid space of the brain. A host may have one to hundreds of cysts.

A proliferating form, called racemose cysticercosis, is occasionally seen. This larva, which occurs mainly at the base of the brain, consists of a grape-like mass containing several connected bladders of various sizes. The protoscolex, if any, is usually dead. It is uncertain whether racemose cysticercosis is an aberrant T. solium cysticercus, the cysticercus of another species, or a sterile coenurus.

Cysticerci may be found almost anywhere, but each species has a predilection for certain tissues. In pigs, T. solium cysticerci are found mainly in the skeletal or cardiac muscles, liver, heart and brain. In humans, this species is most often found in the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, eyes and brain. Serious disease is almost always caused by cysticerci in the CNS (neurocysticercosis) or heart. T. hydatigena cysticerci are usually found in the abdominal cavity. They are generally attached to the omentum, mesentery and occasionally the surface of the liver. The migrating larvae leave hemorrhagic tracks in the liver that later become green/brown and finally, white and fibrotic. Some small cysticerci may also be found in the liver parenchyma, just below the capsule. They tend to degenerate and calcify early. In cattle and pigs, these lesions may resemble tuberculosis. More severe disease, including acute meningoencephalitis, convulsions and death can occur with large numbers of parasites.

Species specific information regarding pigs and how they can be infected:

Taenia asiatica

- Humans are the definitive host.

- The intermediate hosts are domestic and wild pigs, and occasionally cattle, goats or monkeys.

- Dogs, wolves, coyotes, lynxes and, rarely, cats are the definitive hosts.

- Sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, reindeer and other domestic and wild cloven-hoofed animals are the usual intermediate hosts. Rabbits, rodents and humans are rarely infected.

- Humans and are usually the definitive host. Adult tapeworms have also been found in some species of non-human primates.

- The usual intermediate hosts are domestic and wild pigs. T. solium larvae are occasionally found in other intermediate hosts, including sheep, dogs, cats, deer, camels, marine mammals, bears, non- human primates and humans.

Clinical signs are uncommon in pigs infected with T. solium. T. solium can occasionally cause hypersensitivity of the snout, paralysis of the tongue, seizures, fever and muscle stiffness in pigs. Deaths have been reported as the result of myocarditis during experimental infections.

Mortality: The prevalence of infection varies with the parasite. In some parts of the world, up to 43% of the pigs have antibodies to T. solium. Free-roaming pigs have a much greater risk of infection than pigs that are confined to pens. T. solium and T. saginata are both uncommon in livestock in the U.S. T. multiceps infection (gid) can be a common and important disease in some countries or regions, such as parts of the United Kingdom.

Epilepsy

Primary or idiopathic epilepsy is the major cause of recurrent seizures in animals between 1 and 5 years of age. Since no obvious evidence of brain injury is found in primary epilepsy, the probable cause of seizures may be related to a pre-existing or hereditary chemical or functional defect in the brain. The typical seizure due to primary epilepsy is a one to two minute generalized convulsion characterized by collapse, stiffening and/or paddling of the limbs, jaw-chomping, salivation, occasional loss of urine and/or feces, and unconsciousness (no response to calling, touching, etc.). Bear in mind, however, that primary epilepsy may be milder in nature and that not all of the above signs may be seen. A seizure event is typically followed by a "post-ictal" or post-seizure period characterized by incoordination, exhaustion, and disorientation. This period may last for minutes or hours and should not be confused with the actual seizure.

Sources:

http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/pdfs/taenia

http://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam

https://vet.osu.edu/vmc/neurology-and-neurosurgery/epilepsy

The pig in the video above was seen by the vet after this episode. Diagnosis hasn't been fully determined, however, the veterinarian feels like this seizure like activity has been triggered from pain of an unknown source. (But it is thought there may be a problem in the intestines/bowels that may be the source of the pain) This is the third occurrence over the last 3 months and the piggy owners will be keeping an activity log so they can try and determine what the cause of the pain/trigger of the seizure-like activity is. An X-ray was done and blood was drawn and tested there at the clinic, all tests were normal, but a tube of blood was sent off for additional testing/marker identification. They will continue to capture any episodes on film so the vet can get a better idea of what is going on, hopefully they will find out soon and we will most definitely bring you updates when they do! Thank you for sharing this with us Leona!