Spoiled/Moldy Feed

ANY brand of feed has the potential to spoil or mold. If you find that your bag of feed has mold in it, save the bag and the feed and contact the manufacturer. Most big companies have a "contact us" link on their website and those emails are usually directed to the nutrition department. They will probably ask you to send a sample of the feed to them for testing.

There was a time many years ago that my pig feed was ordered for me at a local mom&pop feed store. They usually ordered it once a month for me and several other pig owners and I would go once a month a pick it up. Until one hot summer day, I had no issues with this. That day, I bought a bag, put it in my trunk of my car and drove home (approximately 30 minutes away) and by the time I got home, there were bugs crawling all over the bag of feed and in my trunk. I called the feed store and they offered me a full refund and couldn't explain why the bag of feed had bugs. I drove back, cleaned out my trunk with every cleaning product known to man and brought my container with me on the next trip. We went through several bags of feed before I was satisfied with the bag I finally took home. It was the next day when I was talking to a nutritionist friend that I found out what had happened.

Grain is a unique item in that it typically has these insects in it before packaging. But how did the weevils get there in the first place? You may want to skip this part if you're squeamish but we think it's actually quite fascinating ... A female weevil lays an egg inside a grain kernel. (She can do this up to 254 times!) The egg hatches and for one to five months depending on the season, the larva lives inside and feeds on the kernel as it grows. Upon reaching adulthood, the weevil emerges from the kernel to mate – and look for new grains to invade. So older feed bags are much more at risk than a newer bag of feed.

Keeping the feed in colder conditions kills off any potential grain bugs as well. (also known as weevils) These bugs aren't a health risk to your pig, more of a nuisance for you and your other food products, they do eat away at some of the vital nutrients that the feed contains, so your pig is more at a nutrient deficiency risk. However, keeping the feed in super cold conditions, such as freezing, can lead to another issue. Mold. Freezing feed keeps it fresher longer, but, when freezing, you are also opening a door for a potential mold problem. Once a bag has been frozen, it now needs to be used within a certain amount of days (14 I believe) before you run the risk of the feed starting the mold process. Its better to thaw in open air so it won't trap moisture in a sealed container. You may not be able to see the mold initially, it usually starts at the bottom and by the time you do see or smell it, its been molding for quite some time. Its recommended that the pelleted feed be stored in clear containers so you can always see whats at the top and whats at the bottom.

Never add new feed to the top of an old batch, either use the bottom portion or discard, but not allowing it to be used and dumping new feed on top can lead to the whole new freshly added bag becoming spoiled. Remember, just because you can't see it, doesn't mean its not there. When a food shows heavy mold growth, “root” threads have invaded it deeply. In dangerous molds, poisonous substances are often contained in and around these threads. In some cases, toxins may have spread throughout the food. Obviously everyone will experience things differently, some may not have these kinds of problems in their area while others may have continuous battles with this. Just pay attention. Pay attention to the dates on the bag, pay attention to the feed you have, check periodically for signs of mold or anything else that may be going on with your pigs feed.

Always use containers that seal, screw on lids are best to be sure the lids are secure and there is an air tight seal versus ones you just close. Some rodent and insects can chew through those kind of barriers, but they can't breathe without air. (The 2nd website link also tells you how to handle food/feed with mold, whether its safe to cut it offer if you should discard it all) Brand doesn't matter as much as storage. You can have the top brand feed but if it's been stored for several months in subpar conditions, you can have these kind of issues. Proper storage is essential to your pig getting the best possible feed. Make sure you are cleaning out your storage containers in between filling it up, soap and water is fine, making sure its completely dry before refilling. inspect for cracks or other ways for insects to get in and fixing or replacing containers when needed.

From the pet poison hotline website: Ingestion of moldy food from the garbage or a compost pile puts dogs, cats, and even wildlife at risk for toxicity due to tremorgenic mycotoxins. These toxins may be found in moldy bread, pasta, cheese, nuts, or other decaying matter like compost. Clinical signs include vomiting, agitation, walking drunk, tremors, seizures, and severe secondary hyperthermia. Signs may persist from hours to days, but typically resolve within 24-48 hours with aggressive veterinary treatment. Some of the symptoms may include vomiting, diarrhea, agitation, walking "drunk", tremors, seizures and in some cases, severe hyperthermia. (high temperature) Having moldy feed products can lead to many other illnesses like Listeria or Bacillus, Vitamin A loss is accelerated by spoiled feed as well.

Some molds cause allergic reactions and respiratory problems. And a few molds, in the right conditions, produce "mycotoxins," poisonous substances that can make people sick. When you see mold on food, is it safe to cut off the moldy part and use the rest? To find the answer to that question, delve beneath the surface of food to where molds take root. Molds are microscopic fungi that live on plant or animal matter. No one knows how many species of fungi exist, but estimates range from tens of thousands to perhaps 300,000 or more. Most are filamentous (threadlike) organisms and the production of spores is characteristic of fungi in general. These spores can be transported by air, water, or insects.

http://www.petpoisonhelpline.com/poison/mycotoxin/

http://www.foodreference.com/html/mold-on-food.html

A couple of points to ponder

By Richard Hoyle of the Pig Preserve

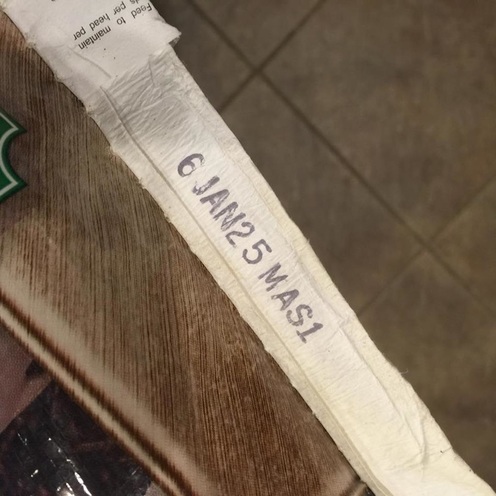

A couple of points to ponder:...First: all feed milled commercially has a "mill date" stamped on it somewhere.....it is usually a julian date (Jan 1=001 and Dec 31= 365)...but it is on every bag of feed milled. (see picture directly below this section) Find it on your brand of feed and you can tell how old the feed is. Refuse to buy feed that is more than a couple of months old. Second:...when leaving the mill, the feed is palletized and shrink wrapped. Then it goes from the mill to an unheated truck and then to one or more warehouses and other trucks before it ends up in your store. This constant change of temperature often causes condensation to build up on the inside of the shrink wrapped pellets sacks and makes them damp....a perfect breeding ground for bacteria and mold.

Also...it takes VERY little ingestion of mold to make a pig terribly ill and the toxins produced by the mold spores can kill a pig.

There was a time many years ago that my pig feed was ordered for me at a local mom&pop feed store. They usually ordered it once a month for me and several other pig owners and I would go once a month a pick it up. Until one hot summer day, I had no issues with this. That day, I bought a bag, put it in my trunk of my car and drove home (approximately 30 minutes away) and by the time I got home, there were bugs crawling all over the bag of feed and in my trunk. I called the feed store and they offered me a full refund and couldn't explain why the bag of feed had bugs. I drove back, cleaned out my trunk with every cleaning product known to man and brought my container with me on the next trip. We went through several bags of feed before I was satisfied with the bag I finally took home. It was the next day when I was talking to a nutritionist friend that I found out what had happened.

Grain is a unique item in that it typically has these insects in it before packaging. But how did the weevils get there in the first place? You may want to skip this part if you're squeamish but we think it's actually quite fascinating ... A female weevil lays an egg inside a grain kernel. (She can do this up to 254 times!) The egg hatches and for one to five months depending on the season, the larva lives inside and feeds on the kernel as it grows. Upon reaching adulthood, the weevil emerges from the kernel to mate – and look for new grains to invade. So older feed bags are much more at risk than a newer bag of feed.

Keeping the feed in colder conditions kills off any potential grain bugs as well. (also known as weevils) These bugs aren't a health risk to your pig, more of a nuisance for you and your other food products, they do eat away at some of the vital nutrients that the feed contains, so your pig is more at a nutrient deficiency risk. However, keeping the feed in super cold conditions, such as freezing, can lead to another issue. Mold. Freezing feed keeps it fresher longer, but, when freezing, you are also opening a door for a potential mold problem. Once a bag has been frozen, it now needs to be used within a certain amount of days (14 I believe) before you run the risk of the feed starting the mold process. Its better to thaw in open air so it won't trap moisture in a sealed container. You may not be able to see the mold initially, it usually starts at the bottom and by the time you do see or smell it, its been molding for quite some time. Its recommended that the pelleted feed be stored in clear containers so you can always see whats at the top and whats at the bottom.

Never add new feed to the top of an old batch, either use the bottom portion or discard, but not allowing it to be used and dumping new feed on top can lead to the whole new freshly added bag becoming spoiled. Remember, just because you can't see it, doesn't mean its not there. When a food shows heavy mold growth, “root” threads have invaded it deeply. In dangerous molds, poisonous substances are often contained in and around these threads. In some cases, toxins may have spread throughout the food. Obviously everyone will experience things differently, some may not have these kinds of problems in their area while others may have continuous battles with this. Just pay attention. Pay attention to the dates on the bag, pay attention to the feed you have, check periodically for signs of mold or anything else that may be going on with your pigs feed.

Always use containers that seal, screw on lids are best to be sure the lids are secure and there is an air tight seal versus ones you just close. Some rodent and insects can chew through those kind of barriers, but they can't breathe without air. (The 2nd website link also tells you how to handle food/feed with mold, whether its safe to cut it offer if you should discard it all) Brand doesn't matter as much as storage. You can have the top brand feed but if it's been stored for several months in subpar conditions, you can have these kind of issues. Proper storage is essential to your pig getting the best possible feed. Make sure you are cleaning out your storage containers in between filling it up, soap and water is fine, making sure its completely dry before refilling. inspect for cracks or other ways for insects to get in and fixing or replacing containers when needed.

From the pet poison hotline website: Ingestion of moldy food from the garbage or a compost pile puts dogs, cats, and even wildlife at risk for toxicity due to tremorgenic mycotoxins. These toxins may be found in moldy bread, pasta, cheese, nuts, or other decaying matter like compost. Clinical signs include vomiting, agitation, walking drunk, tremors, seizures, and severe secondary hyperthermia. Signs may persist from hours to days, but typically resolve within 24-48 hours with aggressive veterinary treatment. Some of the symptoms may include vomiting, diarrhea, agitation, walking "drunk", tremors, seizures and in some cases, severe hyperthermia. (high temperature) Having moldy feed products can lead to many other illnesses like Listeria or Bacillus, Vitamin A loss is accelerated by spoiled feed as well.

Some molds cause allergic reactions and respiratory problems. And a few molds, in the right conditions, produce "mycotoxins," poisonous substances that can make people sick. When you see mold on food, is it safe to cut off the moldy part and use the rest? To find the answer to that question, delve beneath the surface of food to where molds take root. Molds are microscopic fungi that live on plant or animal matter. No one knows how many species of fungi exist, but estimates range from tens of thousands to perhaps 300,000 or more. Most are filamentous (threadlike) organisms and the production of spores is characteristic of fungi in general. These spores can be transported by air, water, or insects.

http://www.petpoisonhelpline.com/poison/mycotoxin/

http://www.foodreference.com/html/mold-on-food.html

A couple of points to ponder

By Richard Hoyle of the Pig Preserve

A couple of points to ponder:...First: all feed milled commercially has a "mill date" stamped on it somewhere.....it is usually a julian date (Jan 1=001 and Dec 31= 365)...but it is on every bag of feed milled. (see picture directly below this section) Find it on your brand of feed and you can tell how old the feed is. Refuse to buy feed that is more than a couple of months old. Second:...when leaving the mill, the feed is palletized and shrink wrapped. Then it goes from the mill to an unheated truck and then to one or more warehouses and other trucks before it ends up in your store. This constant change of temperature often causes condensation to build up on the inside of the shrink wrapped pellets sacks and makes them damp....a perfect breeding ground for bacteria and mold.

Also...it takes VERY little ingestion of mold to make a pig terribly ill and the toxins produced by the mold spores can kill a pig.

What do you do if you open a bag of feed and see mold or clumped food that looks or smells bad? Notify the store you bought it from as well as the manufacturer of the feed. The purpose in doing this is 1) To be able to get a good bag of feed, 2) Let the supplier know there is a problem, 3) Let the manufacturer know the supplier isn't storing the feed correctly or leaving expired bags, or possibly a bad lot of feed that they need to recall. The feed manufacturer may ask you to send a sample to their lab for diagnostic testing and/or have you read a series of numbers printed on the bag indicating the expiration date. Most feed stores will replace your bad bag of feed with a fresh one, but it is important to call the manufacturer PRIOR to returning the bag to the supplier for the reasons stated above. By doing this, you may be saving the lives of pigs you don't even know. Not everyone is attuned to looking in the bag before dumping it into a much larger feed system and if alerted by the store or manufacturer that the whole lot may be spoiled, they may be able to save pigs that would've otherwise eaten potentially toxic agents.

For the main brands of feed (Purina/Mazuri) the "contact us" link on their website will go directly to the head of nutrition for their companies. Those emails do NOT go to a customer service worker and get forwarded, these concerns go straight to the person who helps create the formularies. They typically get back to you within hours, however, nights, weekends and holidays may cause a delay in response.

For the main brands of feed (Purina/Mazuri) the "contact us" link on their website will go directly to the head of nutrition for their companies. Those emails do NOT go to a customer service worker and get forwarded, these concerns go straight to the person who helps create the formularies. They typically get back to you within hours, however, nights, weekends and holidays may cause a delay in response.

Improperly stored feed can be infested with grain mites, the information about proper storage and signs your feed may be affected are in the file below along with suggestions you can give the store about how to lessen the risk.

| mites_in_feed.pdf |

Storing feed for livestock in general is essential in extreme climates where a winter environment may make up half the year. Putting feed up and keeping it in good condition can be difficult, especially in wet summers and other harsh conditions.

Feed spoilage is caused by the growth of undesirable molds and bacteria. Their rapid growth can cause heating of feed, which reduces the energy as well as the vitamins A, D3, E, K and thiamine available to the animal. In addition, moldy feeds tend to be dusty, which reduces their palatability.

The reduced quality of the feed is the most important problem we see in Manitoba when these feeds are given to ruminants (cud chewers such as cattle and sheep). Every winter we receive a number of calls from the public and producers about thin cattle and the birth of weak calves or abortions. It is not unusual we find the problem is from poor feed due to spoilage; the producer did not realize how much the nutrient value of the feed was decreased and had not compensated by properly supplementing.

In addition to spoilage reducing the feed value and palatability, it can also increase the exposure of livestock to harmful molds and bacteria that can cause disease. Although this is not as common a problem in Manitoba ruminants, it is important to understand what these diseases are and why it is difficult to evaluate their threat. Since molds cause most of the problems, this article will focus on them, but occasionally certain bacteria in spoiled feed will also cause disease and these will be discussed as well.

Molds include fungi and yeast and they cause disease in livestock in three major ways:

1. Mycotic: when they grow on or within the animal

2. Mycotoxic: when they produce toxins that are harmful to animals when eaten

3. Allergic: when animals exposed (usually inhaled) develop an immune reaction to mold particles

Mycotoxic diseases are of the most concern but confusion results when people discuss mycotoxins in forages for many reasons:

1. Testing of forages may only be for molds and not for mycotoxins

2. There are over 400 known mycotoxins but routine screens test for only the most common ones

3. Not all mycotoxins have been identified

4. There is incomplete knowledge of tolerance levels in ruminants

5. Treatment and control recommendations lack needed research

Tolerance levels are not well established for ruminants because they have microbes in their rumen that act to naturally detoxify mycotoxins. This ability makes ruminants relatively resistant to these toxins and is probably why we recognize few problems from mycotoxins. However, high producing animals such as dairy cattle have an increased rumen passage rate; this faster processing of contaminated feed may overwhelm the rumen microflora, so that they will not be able to denature all the toxins. Young calves do not have fully developed rumens and are therefore also more susceptible to mycotoxins.

Further complicating the picture is that when mold is seen, it does not necessarily mean that mycotoxin production has occurred. Molds only produce mycotoxins under specific conditions of temperature and humidity. So even though a feed may have large amounts of mold, it may not have produced mycotoxins that present a danger to animals. Fortunately, the conditions necessary for mycotoxin production appear to rarely occur in Manitoba produced feeds.

Mold growth can occur in the field (plant-pathogenic) as well as during processing and storage of harvested products and feed (spoilage). Mold growth accompanied by heating, takes place in most feeds when their moisture content is above 15 or 16 per cent for a period of time.

As mentioned before, the presence of mold does not necessarily mean that the feed can not be used. There are however no concrete recommendations for "safe" mold counts. Recommendations for "high" mold counts range from 100,000 cfu/g to 1,000,000 cfu/g to 10,000,000 cfu/g. Many experts suggest a mold count of 1 million should be considered high, and this feed should be diluted with non-moldy feed, or simply not fed at all. Often a producer will submit a sample for a toxic mold screen and be overwhelmed with millions of spores of certain species, yet there are only few that may be a concern.

Molds in feeds (both hay and grain) - problems and dealing with them

1. Send a representative sample of the feed to a feed testing laboratory for toxic mold analysis. Grain samples should not be ground or rolled. The procedure takes two to four weeks, as a culture of the mold must be grown before it can be determined if it has the potential to be toxic.

2. Presence of a toxic mold does not mean a mycotoxin was produced; you may want to consider still testing for the mycotoxins it may produce.

3. Many molds are known to produce one or more toxins, some of which cannot be identified at present. Clinical signs vary with the

particular mold and toxin. However, it helps to remember that cattle are generally more resistant to mold toxins than either swine or poultry. Young animals are more susceptible than mature animals.

4. Gradually introduce feeds into the ration. Moldy hay is unpalatable, and many problems attributed to mold are actually caused by malnutrition. It takes cattle a few days to adjust to the poor taste and dust; some cattle never adjust.

5. Balance moldy feeds with good quality ingredients. Loss in feed value can be significant (10% +) when molds are present in a feedstuff. Adjustments to the ration should be made accordingly.

6. Some molds (Mucor, Aspergillus) can cause mycotic abortions.

7. When inhaled, mold spores can cause the lungs to become abnormally sensitive to these particular spores. Chronic respiratory disease and even death can occur if exposure to the moldy feedstuff is continued.

8. If problems are encountered, stop using the moldy feed and seek help from a competent source.

9. Silage chopped at moisture levels below 50% requires extra packing to ensure all air pockets are removed from the pile. Removing oxygen from the pile is especially important when many fields are faced with numerous factors inhibiting optimum silage production, including below optimum moisture levels, low plant sugars, poor cob/grain development, and progressing mold development. Proper ensiling will inhibit further mold development which will stop toxin production; however, it will not reduce the toxins already produced. As packing becomes more difficult with lower moisture levels, some producers may choose a non-protein nitrogen source such as anhydrous ammonia to reduce the amount of oxygen in the pile. This option will inhibit further mold development and feed quality losses in silage. Using anhydrous becomes less helpful, however, as moisture levels reach below 30%. The anhydrous ammonia is commonly applied at a rate of 2% of the dry forage weight. At this rate, it may add extra crude protein to feed, but will not add energy.

10. If feed is ensiled and you have not followed proper procedure in the ensiling process (e.g. not properly packed, not enough moisture, too mature, opened pit < 50 days after sealing, excessive aerobic degradation) be cautious in using the feed and be aware of things that you can do differently in the future. Also be critical in how you manage the silage face. Ideally 10 to 12" should be removed for a single time feeding. This can be done on a one or two day interval.

Feed spoilage is caused by the growth of undesirable molds and bacteria. Their rapid growth can cause heating of feed, which reduces the energy as well as the vitamins A, D3, E, K and thiamine available to the animal. In addition, moldy feeds tend to be dusty, which reduces their palatability.

The reduced quality of the feed is the most important problem we see in Manitoba when these feeds are given to ruminants (cud chewers such as cattle and sheep). Every winter we receive a number of calls from the public and producers about thin cattle and the birth of weak calves or abortions. It is not unusual we find the problem is from poor feed due to spoilage; the producer did not realize how much the nutrient value of the feed was decreased and had not compensated by properly supplementing.

In addition to spoilage reducing the feed value and palatability, it can also increase the exposure of livestock to harmful molds and bacteria that can cause disease. Although this is not as common a problem in Manitoba ruminants, it is important to understand what these diseases are and why it is difficult to evaluate their threat. Since molds cause most of the problems, this article will focus on them, but occasionally certain bacteria in spoiled feed will also cause disease and these will be discussed as well.

Molds include fungi and yeast and they cause disease in livestock in three major ways:

1. Mycotic: when they grow on or within the animal

2. Mycotoxic: when they produce toxins that are harmful to animals when eaten

3. Allergic: when animals exposed (usually inhaled) develop an immune reaction to mold particles

Mycotoxic diseases are of the most concern but confusion results when people discuss mycotoxins in forages for many reasons:

1. Testing of forages may only be for molds and not for mycotoxins

2. There are over 400 known mycotoxins but routine screens test for only the most common ones

3. Not all mycotoxins have been identified

4. There is incomplete knowledge of tolerance levels in ruminants

5. Treatment and control recommendations lack needed research

Tolerance levels are not well established for ruminants because they have microbes in their rumen that act to naturally detoxify mycotoxins. This ability makes ruminants relatively resistant to these toxins and is probably why we recognize few problems from mycotoxins. However, high producing animals such as dairy cattle have an increased rumen passage rate; this faster processing of contaminated feed may overwhelm the rumen microflora, so that they will not be able to denature all the toxins. Young calves do not have fully developed rumens and are therefore also more susceptible to mycotoxins.

Further complicating the picture is that when mold is seen, it does not necessarily mean that mycotoxin production has occurred. Molds only produce mycotoxins under specific conditions of temperature and humidity. So even though a feed may have large amounts of mold, it may not have produced mycotoxins that present a danger to animals. Fortunately, the conditions necessary for mycotoxin production appear to rarely occur in Manitoba produced feeds.

Mold growth can occur in the field (plant-pathogenic) as well as during processing and storage of harvested products and feed (spoilage). Mold growth accompanied by heating, takes place in most feeds when their moisture content is above 15 or 16 per cent for a period of time.

As mentioned before, the presence of mold does not necessarily mean that the feed can not be used. There are however no concrete recommendations for "safe" mold counts. Recommendations for "high" mold counts range from 100,000 cfu/g to 1,000,000 cfu/g to 10,000,000 cfu/g. Many experts suggest a mold count of 1 million should be considered high, and this feed should be diluted with non-moldy feed, or simply not fed at all. Often a producer will submit a sample for a toxic mold screen and be overwhelmed with millions of spores of certain species, yet there are only few that may be a concern.

Molds in feeds (both hay and grain) - problems and dealing with them

1. Send a representative sample of the feed to a feed testing laboratory for toxic mold analysis. Grain samples should not be ground or rolled. The procedure takes two to four weeks, as a culture of the mold must be grown before it can be determined if it has the potential to be toxic.

2. Presence of a toxic mold does not mean a mycotoxin was produced; you may want to consider still testing for the mycotoxins it may produce.

3. Many molds are known to produce one or more toxins, some of which cannot be identified at present. Clinical signs vary with the

particular mold and toxin. However, it helps to remember that cattle are generally more resistant to mold toxins than either swine or poultry. Young animals are more susceptible than mature animals.

4. Gradually introduce feeds into the ration. Moldy hay is unpalatable, and many problems attributed to mold are actually caused by malnutrition. It takes cattle a few days to adjust to the poor taste and dust; some cattle never adjust.

5. Balance moldy feeds with good quality ingredients. Loss in feed value can be significant (10% +) when molds are present in a feedstuff. Adjustments to the ration should be made accordingly.

6. Some molds (Mucor, Aspergillus) can cause mycotic abortions.

7. When inhaled, mold spores can cause the lungs to become abnormally sensitive to these particular spores. Chronic respiratory disease and even death can occur if exposure to the moldy feedstuff is continued.

8. If problems are encountered, stop using the moldy feed and seek help from a competent source.

9. Silage chopped at moisture levels below 50% requires extra packing to ensure all air pockets are removed from the pile. Removing oxygen from the pile is especially important when many fields are faced with numerous factors inhibiting optimum silage production, including below optimum moisture levels, low plant sugars, poor cob/grain development, and progressing mold development. Proper ensiling will inhibit further mold development which will stop toxin production; however, it will not reduce the toxins already produced. As packing becomes more difficult with lower moisture levels, some producers may choose a non-protein nitrogen source such as anhydrous ammonia to reduce the amount of oxygen in the pile. This option will inhibit further mold development and feed quality losses in silage. Using anhydrous becomes less helpful, however, as moisture levels reach below 30%. The anhydrous ammonia is commonly applied at a rate of 2% of the dry forage weight. At this rate, it may add extra crude protein to feed, but will not add energy.

10. If feed is ensiled and you have not followed proper procedure in the ensiling process (e.g. not properly packed, not enough moisture, too mature, opened pit < 50 days after sealing, excessive aerobic degradation) be cautious in using the feed and be aware of things that you can do differently in the future. Also be critical in how you manage the silage face. Ideally 10 to 12" should be removed for a single time feeding. This can be done on a one or two day interval.

Signs seen in ruminants

Mycotic abortion

Infection by mold organisms that grow in the fetal membranes (mycotic placentitis) is a common cause of abortion in individual animals. Mycotic placentitis is usually a sporadic cause of abortion affecting a small percentage of cattle in a herd. Cattle housed in the winter can experience an abortion rate of up to 30% due to mycotic placentitis, if feed or bedding is heavily contaminated with molds. Ingested mold is thought to localize in the cows' intestinal tract and then spread to the placenta through the blood. High rates of mycotic placentitis have also been correlated with heavy rainfall during the haymaking season, episodes of subclinical grain overload and with prolonged intensive antibiotic treatment.

The most significant finding in mycotic abortion is placentitis. Affected areas of the placenta are thickened and leathery. Skin and lung infection may develop in the fetus but are much less frequent. Abortions generally occur between 6 - 8 months gestation, calves tend to be small, cows are not clinically affected and subsequent fertility is not affected. Diagnosis indicates mold in affected placenta or in fluid from the fetal stomach.

Because not all of the placenta will be affected it is important to collect and submit the whole placenta along with the aborted calf to the provincial veterinary laboratory in Winnipeg through your veterinarian. If the placenta cannot be submitted the diagnosis is often missed because it may be the only tissue affected.

To prevent mycotic abortions, do not suddenly change the diet of pregnant cattle from all forage to one that includes a large amount of grain, and avoid moldy feeds and bedding when possible.

Abortion and Encephalitis due to Listeria monocytogenes

The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes has a long history in veterinary medicine as a cause of abortion and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and is associated with feeding silage. The bacteria are abundant in the environment, in soil, water and on pasture. It is often associated with a dirty environment because it is found in animal, bird and human stool.

Low numbers of Listeria are likely present in most silage but only multiply and become more numerous in silage improperly cure with a high pH (above 5-5.5) or in areas or aerobic degeneration that can occur in pockets even in good silage. Pockets of aerobic degeneration are often marked by concurrent mold growth. Other moist preserved feeds such as moist brewer's grain and wet spoiled hay can also harbor increased numbers of Listeria.

Infection occurs primarily by eating or inhaling the organism followed by invasion into the blood stream. The infected animal may have a brief period of depression and fever. Animals become nervous if bacteria enter and infect the brain. If the bacteria enter the reproductive tract, it can damage the placenta and fetus causing the fetus to die. Abortion usually follows within two to three days. Abortions may occur without any animals having nervous signs or appearing otherwise abnormal.

Aborted tissues often have a fruity or sweet/sour odour. The diagnosis is made when the bacterium is cultured from the brain, fetal or placental tissues. Culturing the organism from silage or spoiled forages is often unsuccessful because the bacterium tends to be unevenly distributed within the feed, and the sample collected may not be from the right spot.

Encephalitis and abortion due to Listeria monocytogenes is documented in Manitoba. Treatment with antibiotics is the usual practice after an abortion has occurred. No vaccine is available for prevention. Cattle owners should be aware that Listeria also causes disease in humans.

Abortion due to Bacillus bacteria

Abortions due to Bacillus bacteria have been associated with feeding spoiled silage and grain that contains large numbers of bacteria that belong to these species. How it gets into the body and to the placenta is not well understood but likely is similar to mycotic infections. The abortions and changes in the placenta are also similar to what is seen with mycotic infections. As with mycotic infections it is very important to submit the entire placenta along with the aborted calf to the veterinary laboratory to make the diagnosis.

Moldy sweet clover

Sweet clover is a hardy plant that is used in drought and difficult soil conditions. It contains a chemical called coumarol. The chemical can be changed to dicoumarol by fungal action after harvest. Dicoumarol is the same substance found in rat poisons and is a potent anti-clotting compound that can result in excessive bleeding.

Newborn calves are especially susceptible to dicoumarol effects, although older animals and even adults may be affected. Clinical signs include abortion or death of a calf shortly after birth, extensive bleeding from the genital tract of the dam and hemorrhage into the tissues of the calf.

Gathering several pieces of information allows for a diagnosis. There should be a history of feeding moldy sweet clover, findings of hemorrhage and detection of coumarin toxins in blood samples taken from the calf.

Sweet clover hay and silage are difficult to make because the moist nature of the plant encourages mold growth. Fortunately sweet clover does not appear to be commonly used as forage in Manitoba. Most new strains of sweet clover are low in coumarin content.

Vitamin A deficiency

Rations made from actively growing hay or well-cured forages generally satisfy the vitamin A requirements of cattle. However, vitamin A levels fall in feeds stored for extended periods. In addition, losses of vitamin A are accelerated by feed spoilage.

Cattle have reserves of vitamin A in the liver. These reserves are usually not depleted until three to six months after vitamin A levels decline in the feed source. This period usually coincides with the last third of pregnancy when the requirement for vitamin A is the greatest.

Vitamin A deficiency may result if moldy or spoiled forages are fed for long periods. Clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency include reproductive problems in both males and females. Pregnant cows may abort, retain their placenta and develop uterine infection or give birth to weak, dead or blind calves. Bulls with a vitamin A deficiency produce semen with low numbers of sperm and high numbers of abnormalities.

A diagnosis of a vitamin A deficiency is made by analysis of blood samples or a post mortem examination. In Alberta, the occurrence of this problem varies from year to year depending on forage quality.

Allergies

Badly molded feeds contain large numbers of fungal spores. Cattle that inhale these spores may develop a respiratory allergy or a type of interstitial pneumonia which prevents oxygen from getting into the bloodstream.

An affected cow will gasp for breath, and the developing fetus may die due to a lack of oxygen. Abortion usually follows in a couple of days. Diagnosis is based on the signs seen in the cow and a history of respiratory distress before abortion. In humans, an allergic reaction to the fungal spores of feedstuffs is called "Farmer's Lung."

Vomitoxin or Deoxynivalenol (DON)

Deoxynivalenol (DON) is the proper name for the most often detected Fusarium mycotoxin often referred to as Vomitoxin. Having wet, rainy and humid weather from flowering time on promotes the infection of corn and cereal crops by Fusarium species, resulting in ear rot in corn and scab or head blight in wheat, barley, oats and rye.

DON serves as an indicator for spoilage and may be an indicator for the presence of unidentified factors more toxic than DON itself. If DON is present, then the conditions exist for the growth of other potential toxin producers. These toxins are present in the highest concentrations two to three weeks before seed maturity. Ensiling will not decrease the levels of DON.

In some studies fairly high levels of DON in feed has had no effect on cattle (pregnant, feeder, finishing). There has been other information, primarily testimonial in nature however which has suggested reduced feed intake, growth rate and lowered immunity. Also reported are poor feed conversion, general unthriftiness and lower milk production. To be cautious, you may want to avoid feeding DON-contaminated feed to pregnant cows and young calves. Try to keep moldy feed for feeder cattle.

Estrogenism

Molds of the Fusarium family are known to produce estrogenic substances such as zearalenone. Ruminants are not as susceptible to zearalenone as their rumen can break down this mycotoxin, but clinical signs have been reported occasionally in cattle.

Estrogenism occurs most often after livestock eat field-damaged crops that have been put up during cool, wet weather. Once the fungus is established in the grain, it generally requires a period of relatively low temperatures to produce biologically significant amounts of zearalenone.

The ingestion of infected grains can result in the development of feminine characteristics in males, premature sexual development of young females, infertility in adults, abortion, stillbirth and the birth of deformed offspring. Cattle may have swollen vulvas and nipples while vaginal and rectal prolapse may occur. Also seen is a decrease in feed intake and perhaps feed refusal. The effect is most clearly seen in pigs.

Ergotism

Ergot toxicity is most frequently seen during cool, wet seasons. Claviceps purpurea, the offending fungus, infects the seed heads of rye, triticale, wheat, barley, oats and some grasses.

Two forms of disease exist:

1. Nervous form that results in convulsions and staggers in sheep and horses

2. Gangrenous form that causes lameness and the loss of extremities in cattle

Both forms result from the consumption of considerable amounts of fungal tissue. Clinical signs that follow the consumption of infected plants may also include poor hair condition, poor performance, and abortions.

Facial Eczema

The disease is most commonly reported in New Zealand in grazing sheep, cattle, and farmed deer but conditions also exist for it to occur in North America.

It is caused by the mycotoxin sporidesmin produced by Pithomyces chartarum, which grows on dead pasture litter. Warm ground temperatures and high humidity are needed. It causes liver injury which decreases clearance of certain metabolites which results in inflammation of the skin when exposed to sunlight (photodynamic dermatitis). Unpigmented skin is most affected. In sheep, the face is the only site of the body that is readily exposed to ultraviolet light, hence the common name.

Signs include reddening and swelling of unpigmented skin about ~10-14 days after intake of the toxins. Animals will seek shade. Yellowing of the white parts of the eye can occur due to jaundice. Animals can die if liver injury is severe.

Aflatoxins

Aflatoxins are produced by fungi belonging to the family of Aspergillus. It is primarily a problem in US corn and cotton seed and is usually not a field problem in western Canada. Although the occurrence of aflatoxin is rare in Manitoba it is useful to realize what it can cause since it is one of the most potent, animal carcinogens in nature. Also cattle eating feed contaminated with aflatoxins will have decreased productivity, flesh growth and feed conversion. Aflatoxins often cause vaccines to fail and suppress natural immunity.

The reproductive effects of aflatoxins include:

Once the damage has been done, animals can never fully recover from the effects of aflatoxins, even if returned to a toxin-free ration.

Aspergillus spp. grows well on corn and cereal grains. It is a storage fungus and grows well in conditions of relatively high moisture and temperature, but is very persistent under extreme environmental conditions. Roasting, ammoniation at ambient temperatures and some microbial treatments may sharply reduce, but will not eliminate, the content of aflatoxins. The ammoniation process is the most effective at reducing aflatoxins while roasting is the least effective.

Ochratoxins

Fungi such as Aspergillus ochraceus and Penicillium viridicatum can produce ochratoxins in stored feed. Ochratoxins can cause kidney and liver damage. Abortions have also been reported. Fortunately ruminants are very good at breaking down ochratoxins and this mycotoxin is not usually a problem. Exceptions may occur in high producing milk cows and very young stock that have not developed functioning rumens.

PR Mycotoxin in Penicillium molds

Penicillium molds are sometimes found on moldy grains and silage. Certain types (Penicillium roquefortii) can produce a mycotoxin called PR. PR mycotoxin has been associated with abortion, retained placenta and reduced fertility in cattle.

Mycotoxins - A Quick Discussion

1. Because mold is so common and diseases caused by mycotoxins can look similar to other problems it is sometimes easy to blame mycotoxins for the problems seen in a herd.

2. Mycotoxins are however an uncommon cause of disease in Manitoba ruminants. It is important when investigating a herd problem to remember to look at the more common causes of these conditions in Manitoba which are usually due to unbalanced or inadequate rations, infectious diseases such as Bovine Viral Diarrhea, poor water quality, etc.

3. Never the less, mycotoxicosis can occur and it may start as relatively minor problems. The reduction in performance may be negligible. Within days or weeks, the effects of continued mycotoxin consumption on performance (milk production or weight gains) can become more pronounced.

4. Off-feed, ketosis and displaced abomasum problems have been reported to increase significantly with the consumption of mycotoxins. Some animals may develop diarrhea or have signs of hemorrhaging.

5. Estrogenic effects, swollen vulvas and nipples; vaginal or rectal prolapse may occur. Reduced fertility / conception rates or abortions may also be evidence of mycotoxin consumption.

6. The effects of mycotoxins are amplified by production stress. High producing dairy cows and rapidly growing feedlot cattle are more susceptible to the effects of mycotoxins than low producing animals.

7. Effects of molds and mycotoxins on ruminants are highly variable in practice. It is impossible to predict the effects that molds or mycotoxins are likely to have in an individual situation.

8. Ruminants are able to detoxify or transform mycotoxins to other metabolites, mostly less harmful. Ruminants are nevertheless susceptible to the deleterious effects of molds and mycotoxins in feed. Young pre-ruminant and high producing cattle are the most susceptible to the effects of mycotoxins. Decreased feed intake, production losses of 5 - 10% and reduced reproductive performance are the most typical clinical signs of a mold and mycotoxin problem.

9. If molds and/or mycotoxins are present it is prudent to take steps to limit their potentially harmful effects on ruminants.

Summary

The most common consequence of spoiled feed is reduced quality of the feed and inadequate supplementation to the herd to make up for the decreased food value. This in itself can cause poor fertility and problems in newborns, including weak calves, due to protein and energy deficiency.

In addition, abortion and death of newborns due to invasion of the pregnant uterus and placenta by fungi and Bacillus species are diagnosed in several species herds each winter. Occasionally also abortion or brain infection of Listeria is found. Reproductive failure due to Vitamin A deficiency is probably more common then can be established due to lack of confirmatory testing. Allergic problems are also likely under-reported. Reproductive failure caused by moldy sweet clover poisoning and mycotoxicosis appear to be infrequent.

Although mycotoxins appear to be an uncommon problem in ruminants we still must be aware of the possibility. When mycotoxins are suspected in cases of infertility, abortion/death of calves, or poor performance a complet history and a toxicological analysis of feed are required to correctly diagnose the problem.

"Differences of opinion exist regarding the role of molds and mycotoxins in livestock problems basically because their effects on animal health and production are still in a grey area". (Seglar & Mahanna, 1995).

"Mycotoxins can have a very pervasive, yet subclinical effect on both performance and health in ruminants that can easily go unnoticed. If you wait until clinical signs of mycotoxin problems are obvious, you no doubt waited too long". (Eng, 1995).

(Information in this article adapted in part from Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives (Dr. Susan Markus), University of Nebraska, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries).

Source:

http://en.engormix.com/MA-mycotoxins/articles/spoiled-feeds-molds-mycotoxins-t1176/255-p0.htm

(You have to be a registered user in able to access the website)

Mycotic abortion

Infection by mold organisms that grow in the fetal membranes (mycotic placentitis) is a common cause of abortion in individual animals. Mycotic placentitis is usually a sporadic cause of abortion affecting a small percentage of cattle in a herd. Cattle housed in the winter can experience an abortion rate of up to 30% due to mycotic placentitis, if feed or bedding is heavily contaminated with molds. Ingested mold is thought to localize in the cows' intestinal tract and then spread to the placenta through the blood. High rates of mycotic placentitis have also been correlated with heavy rainfall during the haymaking season, episodes of subclinical grain overload and with prolonged intensive antibiotic treatment.

The most significant finding in mycotic abortion is placentitis. Affected areas of the placenta are thickened and leathery. Skin and lung infection may develop in the fetus but are much less frequent. Abortions generally occur between 6 - 8 months gestation, calves tend to be small, cows are not clinically affected and subsequent fertility is not affected. Diagnosis indicates mold in affected placenta or in fluid from the fetal stomach.

Because not all of the placenta will be affected it is important to collect and submit the whole placenta along with the aborted calf to the provincial veterinary laboratory in Winnipeg through your veterinarian. If the placenta cannot be submitted the diagnosis is often missed because it may be the only tissue affected.

To prevent mycotic abortions, do not suddenly change the diet of pregnant cattle from all forage to one that includes a large amount of grain, and avoid moldy feeds and bedding when possible.

Abortion and Encephalitis due to Listeria monocytogenes

The bacterium Listeria monocytogenes has a long history in veterinary medicine as a cause of abortion and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and is associated with feeding silage. The bacteria are abundant in the environment, in soil, water and on pasture. It is often associated with a dirty environment because it is found in animal, bird and human stool.

Low numbers of Listeria are likely present in most silage but only multiply and become more numerous in silage improperly cure with a high pH (above 5-5.5) or in areas or aerobic degeneration that can occur in pockets even in good silage. Pockets of aerobic degeneration are often marked by concurrent mold growth. Other moist preserved feeds such as moist brewer's grain and wet spoiled hay can also harbor increased numbers of Listeria.

Infection occurs primarily by eating or inhaling the organism followed by invasion into the blood stream. The infected animal may have a brief period of depression and fever. Animals become nervous if bacteria enter and infect the brain. If the bacteria enter the reproductive tract, it can damage the placenta and fetus causing the fetus to die. Abortion usually follows within two to three days. Abortions may occur without any animals having nervous signs or appearing otherwise abnormal.

Aborted tissues often have a fruity or sweet/sour odour. The diagnosis is made when the bacterium is cultured from the brain, fetal or placental tissues. Culturing the organism from silage or spoiled forages is often unsuccessful because the bacterium tends to be unevenly distributed within the feed, and the sample collected may not be from the right spot.

Encephalitis and abortion due to Listeria monocytogenes is documented in Manitoba. Treatment with antibiotics is the usual practice after an abortion has occurred. No vaccine is available for prevention. Cattle owners should be aware that Listeria also causes disease in humans.

Abortion due to Bacillus bacteria

Abortions due to Bacillus bacteria have been associated with feeding spoiled silage and grain that contains large numbers of bacteria that belong to these species. How it gets into the body and to the placenta is not well understood but likely is similar to mycotic infections. The abortions and changes in the placenta are also similar to what is seen with mycotic infections. As with mycotic infections it is very important to submit the entire placenta along with the aborted calf to the veterinary laboratory to make the diagnosis.

Moldy sweet clover

Sweet clover is a hardy plant that is used in drought and difficult soil conditions. It contains a chemical called coumarol. The chemical can be changed to dicoumarol by fungal action after harvest. Dicoumarol is the same substance found in rat poisons and is a potent anti-clotting compound that can result in excessive bleeding.

Newborn calves are especially susceptible to dicoumarol effects, although older animals and even adults may be affected. Clinical signs include abortion or death of a calf shortly after birth, extensive bleeding from the genital tract of the dam and hemorrhage into the tissues of the calf.

Gathering several pieces of information allows for a diagnosis. There should be a history of feeding moldy sweet clover, findings of hemorrhage and detection of coumarin toxins in blood samples taken from the calf.

Sweet clover hay and silage are difficult to make because the moist nature of the plant encourages mold growth. Fortunately sweet clover does not appear to be commonly used as forage in Manitoba. Most new strains of sweet clover are low in coumarin content.

Vitamin A deficiency

Rations made from actively growing hay or well-cured forages generally satisfy the vitamin A requirements of cattle. However, vitamin A levels fall in feeds stored for extended periods. In addition, losses of vitamin A are accelerated by feed spoilage.

Cattle have reserves of vitamin A in the liver. These reserves are usually not depleted until three to six months after vitamin A levels decline in the feed source. This period usually coincides with the last third of pregnancy when the requirement for vitamin A is the greatest.

Vitamin A deficiency may result if moldy or spoiled forages are fed for long periods. Clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency include reproductive problems in both males and females. Pregnant cows may abort, retain their placenta and develop uterine infection or give birth to weak, dead or blind calves. Bulls with a vitamin A deficiency produce semen with low numbers of sperm and high numbers of abnormalities.

A diagnosis of a vitamin A deficiency is made by analysis of blood samples or a post mortem examination. In Alberta, the occurrence of this problem varies from year to year depending on forage quality.

Allergies

Badly molded feeds contain large numbers of fungal spores. Cattle that inhale these spores may develop a respiratory allergy or a type of interstitial pneumonia which prevents oxygen from getting into the bloodstream.

An affected cow will gasp for breath, and the developing fetus may die due to a lack of oxygen. Abortion usually follows in a couple of days. Diagnosis is based on the signs seen in the cow and a history of respiratory distress before abortion. In humans, an allergic reaction to the fungal spores of feedstuffs is called "Farmer's Lung."

Vomitoxin or Deoxynivalenol (DON)

Deoxynivalenol (DON) is the proper name for the most often detected Fusarium mycotoxin often referred to as Vomitoxin. Having wet, rainy and humid weather from flowering time on promotes the infection of corn and cereal crops by Fusarium species, resulting in ear rot in corn and scab or head blight in wheat, barley, oats and rye.

DON serves as an indicator for spoilage and may be an indicator for the presence of unidentified factors more toxic than DON itself. If DON is present, then the conditions exist for the growth of other potential toxin producers. These toxins are present in the highest concentrations two to three weeks before seed maturity. Ensiling will not decrease the levels of DON.

In some studies fairly high levels of DON in feed has had no effect on cattle (pregnant, feeder, finishing). There has been other information, primarily testimonial in nature however which has suggested reduced feed intake, growth rate and lowered immunity. Also reported are poor feed conversion, general unthriftiness and lower milk production. To be cautious, you may want to avoid feeding DON-contaminated feed to pregnant cows and young calves. Try to keep moldy feed for feeder cattle.

Estrogenism

Molds of the Fusarium family are known to produce estrogenic substances such as zearalenone. Ruminants are not as susceptible to zearalenone as their rumen can break down this mycotoxin, but clinical signs have been reported occasionally in cattle.

Estrogenism occurs most often after livestock eat field-damaged crops that have been put up during cool, wet weather. Once the fungus is established in the grain, it generally requires a period of relatively low temperatures to produce biologically significant amounts of zearalenone.

The ingestion of infected grains can result in the development of feminine characteristics in males, premature sexual development of young females, infertility in adults, abortion, stillbirth and the birth of deformed offspring. Cattle may have swollen vulvas and nipples while vaginal and rectal prolapse may occur. Also seen is a decrease in feed intake and perhaps feed refusal. The effect is most clearly seen in pigs.

Ergotism

Ergot toxicity is most frequently seen during cool, wet seasons. Claviceps purpurea, the offending fungus, infects the seed heads of rye, triticale, wheat, barley, oats and some grasses.

Two forms of disease exist:

1. Nervous form that results in convulsions and staggers in sheep and horses

2. Gangrenous form that causes lameness and the loss of extremities in cattle

Both forms result from the consumption of considerable amounts of fungal tissue. Clinical signs that follow the consumption of infected plants may also include poor hair condition, poor performance, and abortions.

Facial Eczema

The disease is most commonly reported in New Zealand in grazing sheep, cattle, and farmed deer but conditions also exist for it to occur in North America.

It is caused by the mycotoxin sporidesmin produced by Pithomyces chartarum, which grows on dead pasture litter. Warm ground temperatures and high humidity are needed. It causes liver injury which decreases clearance of certain metabolites which results in inflammation of the skin when exposed to sunlight (photodynamic dermatitis). Unpigmented skin is most affected. In sheep, the face is the only site of the body that is readily exposed to ultraviolet light, hence the common name.

Signs include reddening and swelling of unpigmented skin about ~10-14 days after intake of the toxins. Animals will seek shade. Yellowing of the white parts of the eye can occur due to jaundice. Animals can die if liver injury is severe.

Aflatoxins

Aflatoxins are produced by fungi belonging to the family of Aspergillus. It is primarily a problem in US corn and cotton seed and is usually not a field problem in western Canada. Although the occurrence of aflatoxin is rare in Manitoba it is useful to realize what it can cause since it is one of the most potent, animal carcinogens in nature. Also cattle eating feed contaminated with aflatoxins will have decreased productivity, flesh growth and feed conversion. Aflatoxins often cause vaccines to fail and suppress natural immunity.

The reproductive effects of aflatoxins include:

- abortion

- the birth of weak, deformed calves

- reduced fertility caused by reduced vitamin A levels

Once the damage has been done, animals can never fully recover from the effects of aflatoxins, even if returned to a toxin-free ration.

Aspergillus spp. grows well on corn and cereal grains. It is a storage fungus and grows well in conditions of relatively high moisture and temperature, but is very persistent under extreme environmental conditions. Roasting, ammoniation at ambient temperatures and some microbial treatments may sharply reduce, but will not eliminate, the content of aflatoxins. The ammoniation process is the most effective at reducing aflatoxins while roasting is the least effective.

Ochratoxins

Fungi such as Aspergillus ochraceus and Penicillium viridicatum can produce ochratoxins in stored feed. Ochratoxins can cause kidney and liver damage. Abortions have also been reported. Fortunately ruminants are very good at breaking down ochratoxins and this mycotoxin is not usually a problem. Exceptions may occur in high producing milk cows and very young stock that have not developed functioning rumens.

PR Mycotoxin in Penicillium molds

Penicillium molds are sometimes found on moldy grains and silage. Certain types (Penicillium roquefortii) can produce a mycotoxin called PR. PR mycotoxin has been associated with abortion, retained placenta and reduced fertility in cattle.

Mycotoxins - A Quick Discussion

1. Because mold is so common and diseases caused by mycotoxins can look similar to other problems it is sometimes easy to blame mycotoxins for the problems seen in a herd.

2. Mycotoxins are however an uncommon cause of disease in Manitoba ruminants. It is important when investigating a herd problem to remember to look at the more common causes of these conditions in Manitoba which are usually due to unbalanced or inadequate rations, infectious diseases such as Bovine Viral Diarrhea, poor water quality, etc.

3. Never the less, mycotoxicosis can occur and it may start as relatively minor problems. The reduction in performance may be negligible. Within days or weeks, the effects of continued mycotoxin consumption on performance (milk production or weight gains) can become more pronounced.

4. Off-feed, ketosis and displaced abomasum problems have been reported to increase significantly with the consumption of mycotoxins. Some animals may develop diarrhea or have signs of hemorrhaging.

5. Estrogenic effects, swollen vulvas and nipples; vaginal or rectal prolapse may occur. Reduced fertility / conception rates or abortions may also be evidence of mycotoxin consumption.

6. The effects of mycotoxins are amplified by production stress. High producing dairy cows and rapidly growing feedlot cattle are more susceptible to the effects of mycotoxins than low producing animals.

7. Effects of molds and mycotoxins on ruminants are highly variable in practice. It is impossible to predict the effects that molds or mycotoxins are likely to have in an individual situation.

8. Ruminants are able to detoxify or transform mycotoxins to other metabolites, mostly less harmful. Ruminants are nevertheless susceptible to the deleterious effects of molds and mycotoxins in feed. Young pre-ruminant and high producing cattle are the most susceptible to the effects of mycotoxins. Decreased feed intake, production losses of 5 - 10% and reduced reproductive performance are the most typical clinical signs of a mold and mycotoxin problem.

9. If molds and/or mycotoxins are present it is prudent to take steps to limit their potentially harmful effects on ruminants.

Summary

The most common consequence of spoiled feed is reduced quality of the feed and inadequate supplementation to the herd to make up for the decreased food value. This in itself can cause poor fertility and problems in newborns, including weak calves, due to protein and energy deficiency.

In addition, abortion and death of newborns due to invasion of the pregnant uterus and placenta by fungi and Bacillus species are diagnosed in several species herds each winter. Occasionally also abortion or brain infection of Listeria is found. Reproductive failure due to Vitamin A deficiency is probably more common then can be established due to lack of confirmatory testing. Allergic problems are also likely under-reported. Reproductive failure caused by moldy sweet clover poisoning and mycotoxicosis appear to be infrequent.

Although mycotoxins appear to be an uncommon problem in ruminants we still must be aware of the possibility. When mycotoxins are suspected in cases of infertility, abortion/death of calves, or poor performance a complet history and a toxicological analysis of feed are required to correctly diagnose the problem.

"Differences of opinion exist regarding the role of molds and mycotoxins in livestock problems basically because their effects on animal health and production are still in a grey area". (Seglar & Mahanna, 1995).

"Mycotoxins can have a very pervasive, yet subclinical effect on both performance and health in ruminants that can easily go unnoticed. If you wait until clinical signs of mycotoxin problems are obvious, you no doubt waited too long". (Eng, 1995).

(Information in this article adapted in part from Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives (Dr. Susan Markus), University of Nebraska, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries).

Source:

http://en.engormix.com/MA-mycotoxins/articles/spoiled-feeds-molds-mycotoxins-t1176/255-p0.htm

(You have to be a registered user in able to access the website)

Zearalenone Toxicity

The presence of zearalenone in feed is unavoidable and zearalenone toxicosis is hard to treat. The most practical way to treat zearalenone toxicosis is to use an enterosorbent to prevent the initial dietary absorption by the gut and subsequent conjugated zearalenone compounds from being reabsorbed via enterohepatic circulation. Due to its rapid absorption in the small intestine, the inactivation of zearalenone after ingestion becomes extremely critical in stopping toxicity. By understanding the absorption and metabolism of zearalenone, producers are able to select the right methods to control and treat zearalenone toxicosis more effectively and economically.

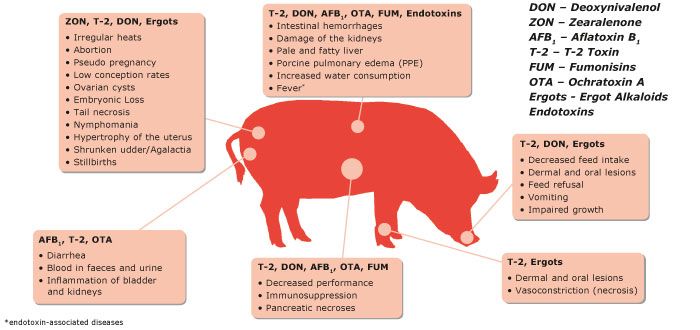

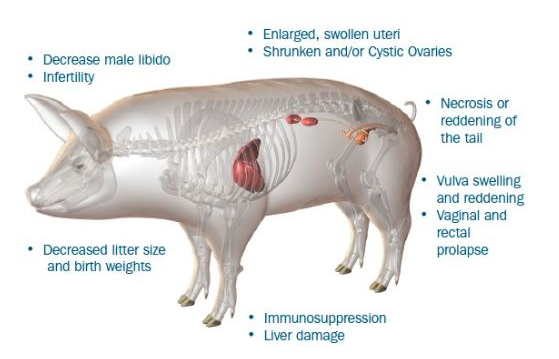

The appearance of a red and swollen vulva in gilts and increased abortions and stillbirths during gestation may indicate zearalenone contamination of the feed. The mycotoxin zearalenone is the greatest contributor to economic loss in swine reproduction.1 It is produced by Fusarium fungi and commonly found in grains worldwide. Production, storage, and climate conditions all contribute to growth of these fungi.2 Due to its similar chemical structure to estrogen, zearalenone causes estrogenic effects in swine,3 and affects all age groups including gilts and sows that are the most sensitive.

Understanding zearalenone's biological effects and its metabolism can help swine producers manage mycotoxicosis properly and prevent economic loss. The chemical structure of zearalenone is 6-(10-hydroxy-6-oxo-trans-1-undecenyl)-b-resorcyclic acid lactone (Fig ure 2). Its optically active isomer l-form is isolated from the mycelia of Fusarium graminearum. It is a colorless crystalline solid with a melting point of 164-165° C, indicating that zearalenone is hard to destroy under normal feed processing. In fact, when zearalenone was present in g round corn no decomposition was seen after 44 h at 150° C.4 Zearalenone is slightly soluble in water and is more soluble in acetone, ether, benzene, alcohols and aqueous alkali. Due to its similarity to estrogen, zearalenone and its metabolites can bind to estrogen receptors, causing estrogenic effects in pigs.

Source: http://en.engormix.com/MA-pig-industry/genetic/articles/zearalenone-toxicity-in-swine

The presence of zearalenone in feed is unavoidable and zearalenone toxicosis is hard to treat. The most practical way to treat zearalenone toxicosis is to use an enterosorbent to prevent the initial dietary absorption by the gut and subsequent conjugated zearalenone compounds from being reabsorbed via enterohepatic circulation. Due to its rapid absorption in the small intestine, the inactivation of zearalenone after ingestion becomes extremely critical in stopping toxicity. By understanding the absorption and metabolism of zearalenone, producers are able to select the right methods to control and treat zearalenone toxicosis more effectively and economically.

The appearance of a red and swollen vulva in gilts and increased abortions and stillbirths during gestation may indicate zearalenone contamination of the feed. The mycotoxin zearalenone is the greatest contributor to economic loss in swine reproduction.1 It is produced by Fusarium fungi and commonly found in grains worldwide. Production, storage, and climate conditions all contribute to growth of these fungi.2 Due to its similar chemical structure to estrogen, zearalenone causes estrogenic effects in swine,3 and affects all age groups including gilts and sows that are the most sensitive.

Understanding zearalenone's biological effects and its metabolism can help swine producers manage mycotoxicosis properly and prevent economic loss. The chemical structure of zearalenone is 6-(10-hydroxy-6-oxo-trans-1-undecenyl)-b-resorcyclic acid lactone (Fig ure 2). Its optically active isomer l-form is isolated from the mycelia of Fusarium graminearum. It is a colorless crystalline solid with a melting point of 164-165° C, indicating that zearalenone is hard to destroy under normal feed processing. In fact, when zearalenone was present in g round corn no decomposition was seen after 44 h at 150° C.4 Zearalenone is slightly soluble in water and is more soluble in acetone, ether, benzene, alcohols and aqueous alkali. Due to its similarity to estrogen, zearalenone and its metabolites can bind to estrogen receptors, causing estrogenic effects in pigs.

Source: http://en.engormix.com/MA-pig-industry/genetic/articles/zearalenone-toxicity-in-swine

Can water go bad?

Biofilm

Everything has a "shelf life", so yes, water can go bad. Another problem with water is the hidden dangers you may not be aware of.

Have you ever rubbed your fingers on the inside of your pigs’ water dish and it was slimy? The slimy stuff that coats the side of your pig’s water bowls (and sometimes even floats around on top) is called “biofilm”. Biofilm is a collection of organic and inorganic, living and dead materials collect on a surface. It is made up of many different types of bacteria bound together in a thick substance, forming a glue like consistency and adhere to a surface. Other places that you might’ve seen biofilm are on your shower curtain and even in your own mouth! Many pig parents are guilty of simply refilling the water bowl over and over without a wash and this becomes a wonderful environment for biofilm to soak around in.

Since biofilm can develop on a surface in just hours, wash your pig’s food bowl after every meal and his water bowl twice a day. If your pig spends time outside, you should have at least one water source in your yard, preferably multiple bowls, pools or whatever you desire. You might need to clean those dishes or products even more frequently, especially in hot weather, which provides a perfect environment for algae and bacteria to grow. This biofilm will also sometimes cause your pig to shy away from the water dish causing dehydration issues such as constipation or electrolyte imbalances. As we know with pigs, lack of water causes a systemic reaction and can really do some damage in a short amount of time.

This film will also grow inside the kiddie pools we typically keep out in the summer months for our precious pet pigs. So that will need to be dumped and cleaned routinely as well. If you notice your pig is not drinking as your pig usually does, check the bowls!! Don't let it become a life-threatening situation before you take action.

When biofilm is introduced into your pig’s system, it can cause urinary tract, bladder and ear infections, so it’s something to consider, when thinking about the health and safety of your pigs. If you wouldn’t drink water from a glass that has been sitting for a week without being washed, why would you expect that to be ok for your pig? The good news is that with proper cleanliness, you can reduce the chance of biofilm in your pet’s system, keeping your pet happily hydrated and biofilm-free.

Written by Brittany Sawyer 2015

Everything has a "shelf life", so yes, water can go bad. Another problem with water is the hidden dangers you may not be aware of.

Have you ever rubbed your fingers on the inside of your pigs’ water dish and it was slimy? The slimy stuff that coats the side of your pig’s water bowls (and sometimes even floats around on top) is called “biofilm”. Biofilm is a collection of organic and inorganic, living and dead materials collect on a surface. It is made up of many different types of bacteria bound together in a thick substance, forming a glue like consistency and adhere to a surface. Other places that you might’ve seen biofilm are on your shower curtain and even in your own mouth! Many pig parents are guilty of simply refilling the water bowl over and over without a wash and this becomes a wonderful environment for biofilm to soak around in.

Since biofilm can develop on a surface in just hours, wash your pig’s food bowl after every meal and his water bowl twice a day. If your pig spends time outside, you should have at least one water source in your yard, preferably multiple bowls, pools or whatever you desire. You might need to clean those dishes or products even more frequently, especially in hot weather, which provides a perfect environment for algae and bacteria to grow. This biofilm will also sometimes cause your pig to shy away from the water dish causing dehydration issues such as constipation or electrolyte imbalances. As we know with pigs, lack of water causes a systemic reaction and can really do some damage in a short amount of time.

This film will also grow inside the kiddie pools we typically keep out in the summer months for our precious pet pigs. So that will need to be dumped and cleaned routinely as well. If you notice your pig is not drinking as your pig usually does, check the bowls!! Don't let it become a life-threatening situation before you take action.

When biofilm is introduced into your pig’s system, it can cause urinary tract, bladder and ear infections, so it’s something to consider, when thinking about the health and safety of your pigs. If you wouldn’t drink water from a glass that has been sitting for a week without being washed, why would you expect that to be ok for your pig? The good news is that with proper cleanliness, you can reduce the chance of biofilm in your pet’s system, keeping your pet happily hydrated and biofilm-free.

Written by Brittany Sawyer 2015