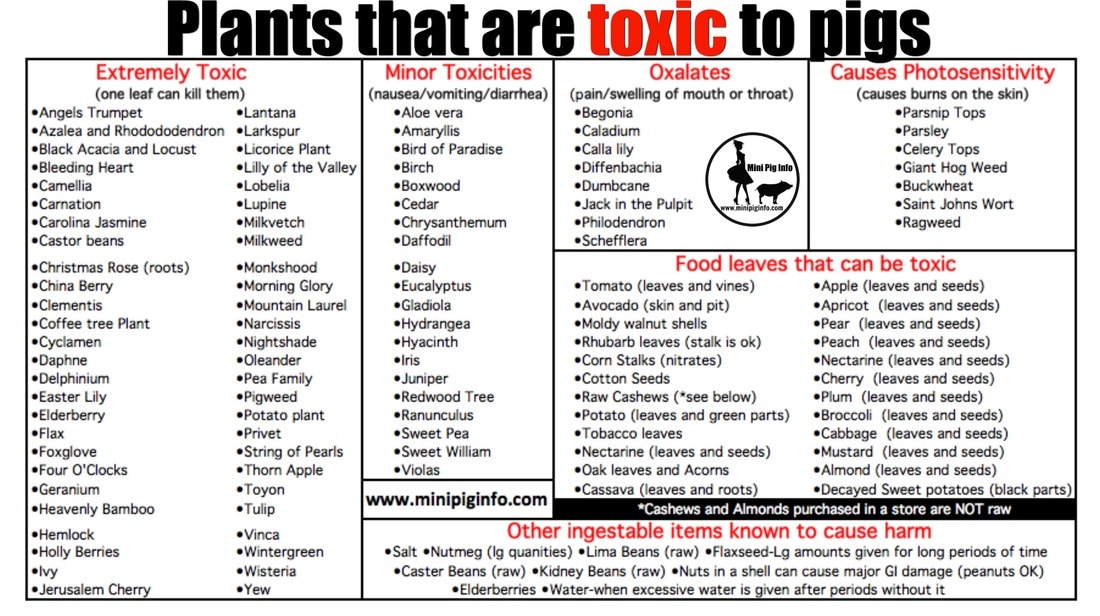

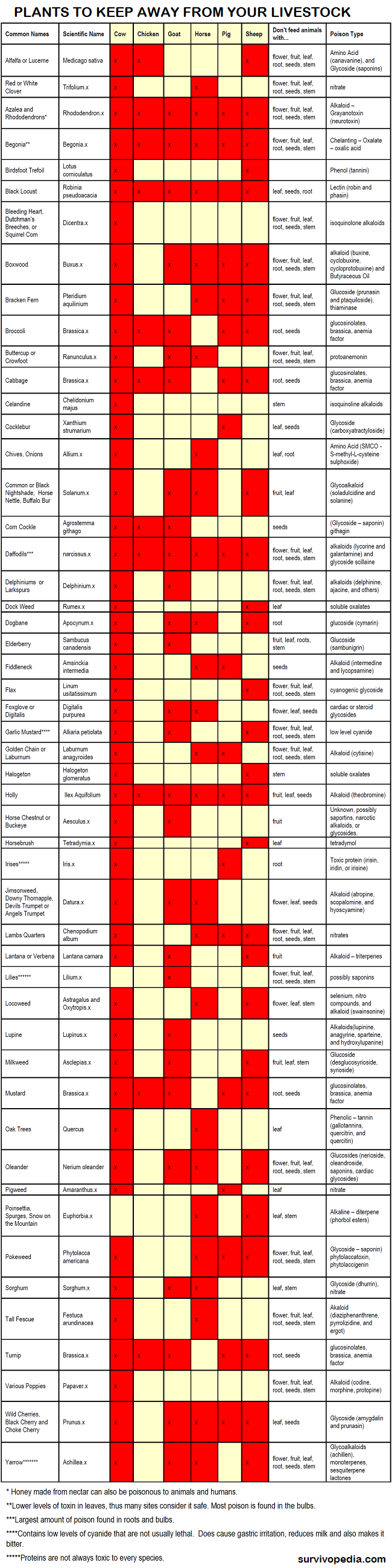

Plants and flowers that are known to be toxic to pigs

There are so many things that are not good for pigs to eat, and if given access, a pig may ingest one of the plants below. Be sure to check your pigs area to be certain none of these plants are able to be eaten by your pig. I have seen others say that pigs won't eat something that is poisonous to them and I have NOT found that to be true. Pigs will be pigs and eat EVERYTHING if allowed.

The size of your pig, the age of your pig and the amount ingested all play a factor in determining if they've been exposed or ingested a "toxic" amount of any of these plants/flowers. If the flower/plant is on the list and you know for sure your pig has ingested some, note the amount, time and type and call the ASPCA or Pet Poison Helpline for information about reversal agents or treatment options.

One animal may have a reaction to any plant while others can eat excessive amounts without any harm, so each individual animal may react differently from others. These are the plants listed on the Toxic to potbelly pigs image that has been passed around for years. Some of the plants listed are NOT toxic at all, but we listed them since we were using that as a guide. Some plants listed are in the same group with other plants of the same species and they were grouped together with their counterparts. We are working to compile a new list with scientific evidence that supports the toxicity to pigs specifically, but this takes time to do the research in order to put that together.

A quick reference guide can be found by downloading the PDF document below created by the Wisconsin Poison Center.

The size of your pig, the age of your pig and the amount ingested all play a factor in determining if they've been exposed or ingested a "toxic" amount of any of these plants/flowers. If the flower/plant is on the list and you know for sure your pig has ingested some, note the amount, time and type and call the ASPCA or Pet Poison Helpline for information about reversal agents or treatment options.

One animal may have a reaction to any plant while others can eat excessive amounts without any harm, so each individual animal may react differently from others. These are the plants listed on the Toxic to potbelly pigs image that has been passed around for years. Some of the plants listed are NOT toxic at all, but we listed them since we were using that as a guide. Some plants listed are in the same group with other plants of the same species and they were grouped together with their counterparts. We are working to compile a new list with scientific evidence that supports the toxicity to pigs specifically, but this takes time to do the research in order to put that together.

A quick reference guide can be found by downloading the PDF document below created by the Wisconsin Poison Center.

| poisonous_plants.pdf |

There are 4 main areas of concern for the toxicity of these plants/flowers to pigs.

Major Toxicity: These plants may cause serious illness or death. If ingested, immediately call the Pet Poison Helpline- (855) 764-7661 or ASPCA- (888) 426-4435. (Have a credit card handy, there is a fee for calling both of these organizations....if your vet calls, they will be charged a fee as well)

Minor Toxicity: Ingestion of these plants may cause minor illnesses such as vomiting or diarrhea. If ingested, call the Poison Control Center or your doctor.

Oxalates: The juice or sap of these plants contains oxalate crystals. These needle-shaped crystals can irritate the skin, mouth, tongue, and throat, resulting in throat swelling, breathing difficulties, burning pain, and stomach upset. Call the Poison Control Center or your doctor if any of these symptoms appear following ingestion of plants.

Dermatitis: The juice, sap, or thorns of these plants may cause a skin rash or irritation. Wash the affected area of skin with soap and water as soon as possible after contact. The rashes may be very serious and painful. Call the Poison Control Center or your doctor if symptoms appear following contact with the plants.

Major Toxicity: These plants may cause serious illness or death. If ingested, immediately call the Pet Poison Helpline- (855) 764-7661 or ASPCA- (888) 426-4435. (Have a credit card handy, there is a fee for calling both of these organizations....if your vet calls, they will be charged a fee as well)

Minor Toxicity: Ingestion of these plants may cause minor illnesses such as vomiting or diarrhea. If ingested, call the Poison Control Center or your doctor.

Oxalates: The juice or sap of these plants contains oxalate crystals. These needle-shaped crystals can irritate the skin, mouth, tongue, and throat, resulting in throat swelling, breathing difficulties, burning pain, and stomach upset. Call the Poison Control Center or your doctor if any of these symptoms appear following ingestion of plants.

Dermatitis: The juice, sap, or thorns of these plants may cause a skin rash or irritation. Wash the affected area of skin with soap and water as soon as possible after contact. The rashes may be very serious and painful. Call the Poison Control Center or your doctor if symptoms appear following contact with the plants.

Plants known to be toxic to mini pigs

|

Scientific Name

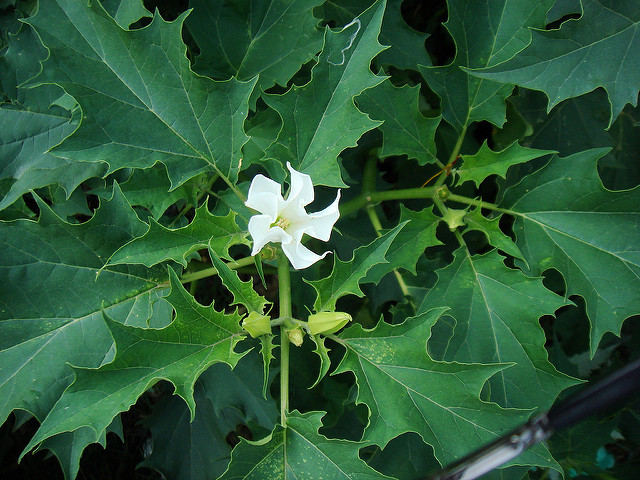

Datura Stramonium L. - Named by Carl Linnaeus as published in Species Plantarum (1753). The genus was derived from ancient hindu word for plant, dhatura. The species name is from New Latin, stramonium, meaning thornapple. Stramonium is originally from from Greek, strychnos (nightshade) and manikos (mad). Common Names of Plants in Datura spp:

Jimsonweed Description Jimsonweed is an annual herb which grows up to 5 feet tall. It has a pale geen stem with spreading branches. Leaves are ovate with green or purplish coloration , coarsely serrated along edges, and 3 to 8 inches long. Flowers are white or purple with a 5-pointed corolla up to four inches long and set on short stalks in the axils of branches. Seeds are contained in a hard, spiny capsule, about 2 inches in diameter, which splits lenghtwise into four parts when ripe. Jimsonweed Distribution Jimsonweed is a cosmopolitan weed of worldwide distribution. It is found in most of the continental US from New England to Texas, Florida to the far western states. Jimsonweed is found in most southern Canadian Provinces as well. It gows in cultivated fields being a major weed in soybeans worldwide. Jimsonweed is common on overgrazed pastures, barnyards, and waste land preferring rich soils. Control of Jimsonweed Because of Jimsonweed's toxic properties, the custom of destroying the plant should be practiced on every farm. Animals should not be allowed to graze on sparse pasture inhabited by Jimsonweed. Hay and silage should not be made from fields until all Jimsonweed has been removed. Soybean and other grain fields infested with Jimsonweed can be controlled by a variety of broadleaf herbicides. Note that herbicides should be applied as directed by a qualified applicator. Jimsonweed Toxicity All parts of Jimsonweed are poisonous. Leaves and seeds are the usual source of poisoning, but are rarely eaten do to its strong odor and unpleasant taste. Poisoning can occur when hungry animals are on sparse pasture with Jimsonweed infestation. Most animal poisoning results from feed contamination. Jimsonweed can be harvested with hay or silage, and subsequently poisoning occurs upon feeding the forage. Seeds can contaminate grains and is the most common poisoning which occurs in chickens. Poisoning is more common in humans than in animals. Children can be attracted by flowers and consume Jimsonweed accidentally. In small quantities, Jimsonweed can have medicinal or haulucinagenic properties, but poisoning readily occurs because of misuse. Ingestion of Jimsonweed caused the mass poisoning of soldiers in Jamestown, Virginia in 1676. Jimsonweed toxicity is caused by tropane alkaloids. The total alkaloid content in the plant can be as high as 0.7%. The toxic chemicals are atropine, hyoscine (also called scopolamine), and hyoscyamine. Clinical Signs of Jimsonweed Poisoning Jimsonweed poisoning occurs in most domesticated production animals: Cattle, goats, horses, sheep, swine, and poultry. Human poisoning occurs more frequently than livestock poisoning making jimsonweed unusual among most poisonous plants. Early Signs:

Fatal Cases:

Jimsonweed - Jamestown Story

Captain John Smith, founder of Jamestown In 1676, British soldiers were sent to stop the Rebellion of Bacon. Jamestown weed (Jimsonweed) was boiled for inclusion in a salad, which the soldiers readily ate. The hallucinogenic properties of jimsonweed took affect. As told by Robert Beverly in The History and Present State of Virginia (1705): The soldiers presented "a very pleasant comedy, for they turned natural fools upon it for several days: one would blow up a feather in the air; another would dart straws at it with much fury; and another, stark naked, was sitting up in a corner like a monkey, grinning and making mows at them; a fourth would fondly kiss and paw his companions, and sneer in their faces with a countenance more antic than any in a Dutch droll. "In this frantic condition they were confined, lest they should, in their folly, destroy themselves - though it was observed that all their actions were full of innocence and good nature. Indeed they were not very cleanly; for they would have wallowed in their own excrements, if they had not been prevented. A thousand such simple tricks they played, and after 11 days returned themselves again, not remembering anything that had passed." Sources: http://poisonousplants.ansci.cornell.edu/jimsonweed |

|

Giant Hogweed

Extremely Toxic This plant causes extreme sunburn and can cause blindness, in some cases. If the toxic sap gets into your eyes, can cause you not to be able to see. The blisters on the skin can last up to 6 years according to Va tech. Birds carry the seeds and drop them in different areas of the country. It’s a threat in many states across the US, and is definitely growing in NY, VA, MD, NH, OH, OR, WA, MI, VT, PA and ME. The toxic ingredient is known as photosensitizing furanocoumarins. The light sensitize skin reaction causes dark painful blisters that can form within 48 hours and can last anywhere from a few months to 6 YEARS. Touching giant hogweed can also cause long term sunlight sensitivity and blindness if the sap gets into the eyes. This is the case even if you simply brush up against the bristles of this toxic plant. The Department of Health recommends that you wash it off with cold water immediately and get out of the sun. A toxic reaction can begin as soon as 15 minutes after contact. Apply sunscreen to the affected areas since this can prevent further reactions if you're stuck outside. Compresses soaked in an aluminum acetate mixture - available at pharmacies - can provide relief for skin irritations. If hogweed sap gets into the eye, rinse them with water immediately and put on sunglasses. If you live near giant hogweed you can mow or weed-whack the plant before you touch it to prevent future exposure, right? Think again. That will just send up new growth and potentially expose you to toxic sap. Call a professional or local authorities who can properly destroy the plant and its seeds. Sources: https://wtkr.com/dangerous-giant-hogweed-plant https://www.sciencealert.com/invasive-toxic-giant-hogweed-burns-skin-blindness |

|

Azalea's

Description Rhododendron is a genus of a shrub with about 800 species worldwide. Its ovate evergreen or deciduous leaves are alternate, 1/2 - 8 inches in length depending on variety, with smooth untoothed margins. They are dark green with a glossy upper surface and a dull underside. Large trusses of bell-shaped flowers bloom from spring to early summer. Plants are available with flowers in colors such as white, purple, deep rose, red, yellow, and orange. Rhododendron and its closely related azalea have been hybridized for many uses in gardens and rarely reach above 3-5 feet tall in northern states including Illinois. Distribution In Illinois, most species found are ornamental types that usually thrive in protected areas of gardens. But these plants can be found nationwide in the USA. Tall, wild varieties can reach over 35 feet high, and are found throughout the coastal mountain ranges from New York to Georgia. Designated as West Virginia's state flower, rhododendrons are particularly abundant in the Great Smoky and the Blue Ridge mountains. Species in the Pacific northwest from northern California to British Columbia vary in heights. Conditions of poisoning All parts of the plant, but especially the foliage, contain the poison, and two or three leaves may produce severe toxicosis. Sucking flowers free of nectar may produce serious illness. Rhododendrons are more likely to retain green leaves year round than are most other plants, and therefore most toxicoses occur in the winter and early spring, when other forage is unavailable. Toxic principle All parts of this plant contain toxic resins (andromedotoxins, now commonly referred to as grayanotoxin) with the leaves being the most potent. Grayanotoxin produces gastrointestinal irritation with some hemorrhage, secondary aspiration pneumonia, and sometimes renal tubular damage and mild liver degeneration. Clinical signs Clinical signs usually appear within 6 hours of ingestion. Affected animals may experience anorexia, depression, acute digestive upset, hypersalivation, nasal discharge, epiphora, projectile vomiting, frequent defecation, and repeated attempts to swallow. There also may be weakness, incoordination, paralysis of the limbs, stupor, and depression. Aspiration of vomitus is common in ruminants and results in dyspnea and often death. Pupillary reflexes may be absent. Coma precedes death. Animals may remain sick for more than 2 days and gradually recover. Source: http://www.library.illinois.edu/vex/toxic/rhodo/rhodo.htm |

|

Robinia pseudoacacia

Common name: Robinia, Black locust, False acacia Comments:

Toxicity to pigs: Possible Palatability: Moderate Toxicity to Other Species: Potentially toxic to sheep, cattle, horses, and poultry. Poisonous Principle:

Effects: Signs and symptoms

In humans, dizziness, vomiting, gastro- enteritis, dilation of the pupils, convulsions, slowing of heart rate. Health and Production Problems:

Treatment: See Vet or Doctor Integrated Control Strategy: Control achieved by grazing strategy. Source: http://www.weeds.mangrovemountain.net/data/Robinia |

|

Scientific name: Dicentra spp.

Alternate names: Dicentra, Dutchman's breeches, white eardrops, steer's head, soldier's cap, butterfly banner, kitten breeches, Bleeding Hearts Poisonous to: Cats, Dogs, Cows, Pigs Poison type: Plants Level of toxicity: Mild to Moderate Common signs to watch for:

Bleeding Heart plants are not only toxic to animals but humans as well. Although aesthetically pleasing, this plant contains soquinoline alkaloids. Alkaloids negatively affect animals, most commonly cattle, sheep, pigs and dogs. Source: www.petpoisonhelpline.com/poison/bleeding-hearts |

|

Carolina Jessamine

Toxicity: The toxic principles are the alkaloids gelsemine, gelseminine, and gelsemoidine. These toxins are related to strychnine. Livestock are affected, usually in the winter and spring months, from eating any part of the plant. Humans have been poisoned from sucking nectar from the flowers or from eating honey made from the flowers. Bees have died from consuming the nectar. Symptoms: Animals are usually found staggering and incoordinated, with dilated eyes and convul- sive movements. Often the animals are found down in comatose condition. Death usually occurs soon after animals become comatose. Treatment: There is no specific treatment. Provide supportive therapy with intravenous fluids. Give cardiac and respiratory stimulants such as caffeine and sodium benzoate. |

|

Showy Crotalaria- Annual herb, 0.2 to 0.5 m tall, puberulent to glabrate. Leaves simple, alternate. Lower leaves spatulate, 2 to 3 cm long, 6 to 15 mm wide; upper leaves oblanceo- late, 3 to 6 cm long, 4 to 10 mm wide. Stipules conspicuous, tardily deciduous, fused to stem. Flowers showy, 1.5 to 2.5 cm long, yellow, in terminal racemes. Widely dis- tributed from Florida to Texas in Coastal Plain and Piedmont; abun- dant along roadsides, in fields, and in waste places; once cultivated as a green manure crop.

The toxic principle is the alkaloid monocrotaline. Chickens, horses, cattle, and swine are the species usually affected, but sheep, goats, mules, and dogs can be affected to a lesser degree. Part of plant that is poisonous All parts of the plant are poisonous, whether green or dried in hay. The seeds are es- pecially poisonous. Poisoning occurs when animals consume the green plant, hay contaminated with crotalaria, or dried seed in harvested grain. Signs/Symptoms of acute poisoning Swine may exhibit either an acute form, characterized by sudden gastric hemorrhage and death, or a chronic form with anemia, ascites, loss of hair, and unthriftiness. Treatment There is no specific treatment. Source: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs |

|

Castor bean (Ricinus communis)

The castor bean is very, very toxic...even one seed (the "bean") ingested by a child or pet can be fatal. The seeds contain the toxins ricin and albumin. This common introduced plant has naturalized throughout the USA and thrives in a variety of habitats. If you think your pet has eaten or chewed on a castor bean, contact your veterinarian immediately. Do not wait for symptoms (commonly vomiting and diarrhea) to appear. |

|

The entire Christmas rose-plant is toxic. Out of all the organs particularly the rhizome contains ill-defined compounds. The powerful toxins present are not destroyed in drying or storage. Both animals and humans are affected. Hellebores are said to have a burning taste.

All Helleborus sp. are claimed to be toxic. Some current authors propose lack of the effective cardiac glycosides in H. niger and suggest that the prior knowledge on the presence of these compounds in effective concentrations is derived from the use of preparatives contaminated by H. viridis, the powerful toxicity of which is also currently proven. Whether there is wide diversity in the presence of effective toxins among H. niger strains is not known. The plants in the family Ranunculaceae contain a variety of powerful toxins. The toxic compounds found in H. niger in addition to cardiac glycosides helleborin, hellebrin and helleborein include saponosides and the ranunculoside derivative, protoanemonine. In Europe, Helleborus niger is considered one of the most traditional and noble seasonal plants of the Christmas time. Serious poisoning following ingestion is rare. The knowledge of the powerful toxicity or rather the medicinal potential of Christmas rose goes back to the Middle Ages, when it was extensively used by herbalists, and even to earlier times. Theophrastus (Greek philosopher, c. 372-287 BC., "the father of Botany") and Dioscorides (Greek physician, 1st century AD., author of De Materia Medica) have mentioned Christmas rose in their works. Pliny has mentioned the use of H. niger as early as in 1400 BC. by a soothsayer and physician Melampus, after whom the plant has sometimes been referred to as "melampode". Description of the plant Classification and nomenclature Botanically, Christmas rose is classified to belong to the plant family Ranunculacae - the Buttercup Family, in which it fits well having the characteristic flower and fruit morphology. The scientific name Helleborus derives from the Greek name for H. orientalis "helleboros"; "elein" to injure and "bora" food. Niger refers to the black color of the roots of the Christmas rose plant. The nameHelleborus niger was given to the plant by Carl von Linné. Common names of H. niger include black hellebore, Christmas rose and Easter rose (Finnish: jouluruusu, Swedish: Julros, German: Schwarze Nieswurz, Christrose, French: Hellébore noir, Rose de Noel, Italian: Elleboro nero, Fava di lupo, Rosa di Natale. Characteristics Christmas rose is an evergreen rhizomatous perennial reaching 35 cm (13,5 in.) in height. In its native habitat, the Christmas rose flowers from December through April, the season when snow is escaping leaving open spots for the first spring makers to grow, each clump producing groups of 2 or 3 large nodding flowers. By the end of and during the flowering season part of the old leaves die (lasting only for one year) and new ones begin to grow. Also the new flower buds are formed within the short growth season, generally from February through May. The growth season of Christmas rose is thus short; four to five months. H. niger produces a floral stalk but no true leafy stems. LEAVES: The leaves are basal, persistent, alternate, palmately cleft, with long petioles. They consist of 7-9 leaflets which are dark green, shiny, tough, narrow and lanceolate. FLOWERS: Very few-flowered; showy flowers, usually borne singly on red-spotted peduncles, are white (suffused in pink), sepals: 5, large petaloid; petals small, turbular, claved; stamens: numerous, the outer 8-10 modified into staminoides; pistils: usually 3 or 4; style: erect, slender. |

Other toxic Christmas decorations

|

Source: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs

|

China Berry

Toxicity: The toxic principles are tetranortriterpene neurotoxins and unidentified resins. The fruit (berries) are the most toxic part of the tree. The leaves, bark, and flowers are only mildly toxic and usually cause no problem. Most poisonings occur in the fall or winter when the berries ripen. Swine and sheep are most often affected. Toxicity may occur after consumption of more than 0.5 percent of body weight. Poultry and cattle can be poisoned, but larger amounts are required. Children have been poisoned by eating the berries. Symptoms: The gastrointestinal tract is affected; therefore, common symptoms include vomiting and diarrhea. Occasionally, the central nervous system is affected, and animals are se- verely depressed or excited. Treatment: Evacuate the affected animal’s gastrointestinal system. Use lentin-carbocal gastroin- testinal protectives, respiratory stimulants, and caffeine. |

|

Coffee senna/Senna occidentalis

Coarse herb very similar to S. obtusifolia but having mostly eight or more leaflets rather than four to six. Pods flattened whereas those on S. obtusifolia are nearly four- sided. Pods tend to be straighter and shorter than those of S. obtusifolia. Toxicity The toxic principles have not been clearly established. The seeds appear to exert their toxicity upon the skeletal muscles, kidney, and liver. The leaves and stem, whether green or dry, also contain toxin. Sicklepod is much more prevalent but somewhat less toxic than coffee senna. Animals can be poisoned by consuming the plant in the field, in green chop, in hay or if the seed is mixed with grain. Cattle are susceptible to the effects of these plants, and other animals are probably susceptible as well. Symptoms Diarrhea is usually the first symptom. Later, the animals go off feed, appear lethargic, and tremors occur in the hind legs, indicating muscle degeneration. As muscle degenera- tion progresses, the urine becomes dark and coffee colored. The animal becomes recum- bent and is unable to rise. Death often occurs within 12 hours after the animal goes down. There is no fever. Treatment Once animals become recumbent, treatment is usually ineffective. Do not give sele- nium and Vitamin E injections because they will potentiate the disease. Vitamin E is the more important component in this potentiation. |

Source: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs

|

|

Creeping Indigo The Indigofereae are a small tribe of often very attractive, pink to red-flowered shrubs and herbs. The largest genus is Indigofera which is pantropical, with 75% of the ~750 species restricted to Africa–Madagascar, and the rest in the Sino-Himalayan region, Australia, Mexico, and Brazil. Because of their complex chemistry, Indigofera contain many toxic and medicinally used species. These toxic chemicals have evolved as a defensive response to predation by herbivores and pathogens. Other Indigofera are economically important indigo dye-producing and pasture legume species that occupy an extremely wide range of different habitats. Indigofera spicata is native to East Africa and Madagascar, Indonesia, and the Philippines. It was valued as a cover crop in coffee estates in Africa and was introduced into India, Java, Malaya, and the Philippines both as ornamental ground cover and a cover crop for tea, rubber, oil palm, and sisal plantations. It has also been introduced into Australia, several pacific islands and the Caribbean. It has been proven to be toxic to horses, presumably to pigs as well.

Signs of Creeping Indigo Toxicity Consumption of 10 pounds I. linneae daily for 3 weeks is sufficient to cause disease. Both neurologic and non-neurologic signs are seen. Non-neurologic signs. There may be weight loss, inappetance, high heart and respiratory rates, labored breathing, high temperature (a rare finding), hypersalivation (ptyalism) or foaming from the mouth, dehydration, pale mucous membranes, feed retention in the cheeks (quidding), halitosis, watery discharge from the eyes (epiphora) and squinting (blepharospasm), light sensitivity, corneal opacity, corneal ulceration and neovascularization, severe ulceration of the tongue and gums, and prominent digital pulses without other signs of laminitis. Toxins Over the last decade, there has been resolution of the previous confusion about the roles of the two putative toxins of creeping indigo, 3-nitropropionate (3-NPA) and indospicine. It is now clear that 3-NPA causes the largely irreversible neurologic signs described above while indospicine causes the corneal edema, ulcerations, and other non-neurologic signs. Each of these toxins is described briefly: 3-nitropropionate. 3-NPA is a highly toxic compound, produced by the plant primarily as defense against destruction by herbivores. This nitrotoxin is by no means unique to Indigofera but is produced as anti-herbivore defense by a vast array of plants and fungi. Poisoning associated with 3-NPA therefore occurs quite commonly in a variety of settings and the mechanism is well understood. The toxin is a potent and irreversible inhibitor of mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase, a key enzyme in transforming glucose and oxygen into useable energy. Nerve cells are extremely vulnerable to energy deprivation, thus accounting for the early and prominent neurologic signs seen with all types of 3-NPA toxicity. 3-NPA accounts for 0.24 to 1.5% of the dry matter of creeping indigo. Because it is metabolized quickly, it is unlikely to be found in the serum of affected animals. Indospicine is a non-protein amino acid. It is toxic to the liver because of antagonism to the essential amino acid arginine, with which it competes. One of its principal toxic actions is inhibition of nitric oxide synthase, an action likely associated with the development of corneal edema and ulceration of mucous membranes. Although horses are relatively resistant to the liver damaging effects of this toxin, it persists in the tissues of horses dying or killed with the disease and these tissues are potentially toxic if fed to dogs. Indospicine accounts for 0.1 to 0.5% of the dry matter of creeping indigo and it can be detected in the serum of affected animals. Treatment and prevention There is no effective treatment, only management of symptoms. Source: http://largeanimal.vethospitals.ufl.edu/2014/11/03/creeping-indigo-toxicity/ |

|

Common Name: Daphne

Scientific Name: Daphne spp. Species Most Often Affected: cats, dogs, humans Poisonous Parts: berries, all Primary Poisons: mezereinic acid anhydride The plants contain irritant chemicals that cause pain, burning, and tingling sensations on exposed skin. These sensations are intensified on mucous membranes in the mouth, throat, and stomach after ingesting the fruits. More serious symptoms also occur in humans, including kidney damage, which may lead to death. With the exception of February daphne, the other Daphne species and cultivars are found only as ornamental plants. Horses and swine have been poisoned and have died after ingesting daphne leaves or berries, although poisoning of animals is a rare occurrence. Family pets can be poisoned if they have access to the plants. http://www.cbif.gc.plants-information-system/all-plants-scientific-name/daphne-mezereum/ |

|

The beautiful Cyclamen is highly toxic to pets who ingest it. The toxins include terpenoid saponins which can cause salivation, vomiting, diarrhea, heart rhythm abnormalities, and even seizures and death. This plant can also cause dermatitis to the area of the skin that touches it.

If you think your pet has eaten any part of this plant, contact your veterinarian immediately. Source: http://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/toxic-plant-garden |

|

Scientific Name: Delphinium spp.

Common Name: Delphiniums, Larkspurs Species Most Often Affected: cattle, humans, goats Poisonous Parts: all Primary Poisons: alkaloids delphinine, ajacine, and others Dwarf larkspur, staggerweed. Delphinium tricorne Michx. Crowfoot Family (Ranunculaceae) Description: Stout perennial, 4-35 inches high. Leaves alternate and very deeply lobed. Flowers spurred, blue or occasionally white, arranged in terminal clusters, appearing in spring. The root is a tuberous cluster. Commonly found in rich, open woods and along streams. The annual larkspur (Delphinium Ajacis L.), which often escapes from gardens and establishes itself as a weed ln fields and roadsides, is also poisonous. Conditions of poisoning: Larkspur contains several very poisonous alkaloids, including delphinine, and is most poisonous in the early stages of growth, during April and May. Poisoning occurs when stock grazes in woodland pastures before other green herbage is available. Cattle are the most susceptible, but horses and sheep can be poisoned by eating large quantities. Symptoms: The symptoms of larkspur poisoning differ according to the amount eaten and the animal's tolerance. Small amounts may cause loss of appetite; excitability, staggering, and constipation. Severe symptoms that develop when an animal eats large quantities are slobbering, vomiting, colic, bloating, and convulsions. Death is due to respiratory paralysis. Treatment: Protect animals from excitement by keeping them in a quiet place and give them such drugs as chloral hydrate or one of the barbiturates. Epsom salts may be given to help the constipation. Other drugs should be given to relieve the animal. It may be necessary to treat the animal for bloat. |

|

Common name: Easter lily, Trumpet lily

Scientific name: Lilium longiflorum; L. tigrinum (Liliaceae) Entire plant is toxic. Kidney system failure in cats 2 to 4 days post-ingestion. Not reported toxic to other species. Vomiting, depression, loss of appetite within 12 hours post-ingestion. Treatment suggestions: Emetics (induce vomiting), activated charcoal, saline cathartic, and nursing care—as for renal failure—within hours of ingestion. Delayed treatment is associated with poor prognosis. Source: www.merckvetmanual.com//plantspoisonoustoanimals. |

|

Elderberries

This berry is often used in juicing, but in 1983, a group of people gathered together at a religious retreat and the majority became sick after drinking the elderberry juice. The CDC report states that a few pigs died from elderberries and that the root is the most potent. Editorial Note: The indigenous elder tree of the western United States, Sambucus mexicana, can grow to 30 feet and produces small (1/4-inch), globular, nearly black berries that can be covered with a white bloom at maturity. The berries are juicy and edible when mature. The cooked berries are commonly eaten in pies and jams, and berry juice can be fermented into wine. The fresh leaves, flowers, bark, young buds, and roots contain a bitter alkaloid and also a glucoside that, under certain conditions, can produce hydrocyanic acid. The amount of acid produced is usually greatest in young leaves. There may be other toxic constituents in this plant. The root is probably the most poisonous and may be responsible for occasional pig deaths; cattle and sheep have died after eating leaves and young shoots. Source: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00000311.htm |

|

Flax provides oil as well as clothing fibres (linen). It also contains cyanogenic glycosides, though their concentration varies with species, season, and climate.

The primary threat of flax is to livestock if they are fed flax regularly, as an ingredient of prepared meal or seedcake. Poison location Seeds, particularly those formed into linseed cake or meal for livestock. Poison type Glycoside, producing cyanide. Amount differs with variety and climate or season. Typical poison scenario Processed linseed cake or meal fed to livestock. The use of flax seed in cooking and baking is completely safe! Symptoms In very small doses, the human digestive tract is capable of breaking down plant cyanides into harmless compounds. However, larger doses cause anxiety, confusion, dizziness, headaches, and vomiting. In severe poisoning, breathing difficulty, increased blood pressure and heart rate, and kidney failure are followed by coma and convulsions. Death may then occur rapidly from respiratory arrest. Source: http://www.novascotia.ca/museum/flaxpoison/ |

|

Wild 4 o'clock

Description: This herbaceous perennial plant is about 2-4' tall, branching occasionally. The stems are glabrous and light green; they are often angular below, becoming more round above. The dark green opposite leaves are up to 4" long and 3" across. They are cordate (somewhat triangular-shaped) and hairless, with smooth margins and short petioles. Some of the upper leaves near the flowers are much smaller and lanceolate. The upper stems terminate in clusters of magenta flowers on long stalks. Usually, there are a few hairs on these stalks and the pedicels of the flower clusters. A cluster of 3-5 flowers develop within a surrounding green bract with 5 lobes; this bract has the appearance of a calyx. These flowers are trumpet-shaped and span about ½" across, or slightly less. There are no petals; instead, a tubular calyx with 5 notched lobes functions as a corolla. At the center of each flower are 3-5 exerted stamens with yellow anthers. The blooming period is usually during the early summer and lasts about a month. There is little or no floral fragrance. The flowers typically open during the late afternoon, remain open at night, and close during the morning. The greyish brown seed is up to 3/8" (10 mm.) long and pubescent; it has 5 ribs. The root system consists of a thick dark taproot that is fleshy or woody. This plant spreads by reseeding itself. Wild Four-O'Clock tends to increase in areas disturbed by livestock; it is unclear if these animals eat this plant. Deer reportedly avoid it. The seeds and roots are known to be poisonous, although pigs may dig up the roots and eat them. Roots and seeds are the toxic part of this plant/flower. |

|

Foxglove

A very common plant, both in the garden and the wild, with the potential to kill in quite small amounts but also the source of medication which has saved thousands of lives since its discovery in 1775. How Poisonous, How Harmful? Contains cardiac glycosides called digitoxin, digitalin, digitonin, digitalosmin, gitoxin and gitalonin. During digestion these produce aglycones and a sugar. The aglycones directly affect the heart muscles. It produces a slowing of the heart which, if maintained, usually produces a massive heart attack as the heart struggles to supply sufficient oxygen to the brain. The acceleration of the heart ahead of this, sometimes leads to it being wrongly said to increase the heart rate. The raw plant material is, however, emetic and eating a large amount may produce vomiting thus expelling the cardiac poisons before they can do serious harm. Source: http://www.thepoisongarden.co.uk/atoz/digitalis.htm |

|

Geranium

Additional Common Names: Many cultivars Scientific Name: Pelargonium species Family: Geraniaceae Toxicity: Toxic to Dogs, Toxic to Cats, Unknown if toxic to pigs, but it's better to be safe than sorry Toxic Principles: Geraniol, linalool Clinical Signs: Vomiting, anorexia, depression, dermatitis Source: http://www.aspca.org/pet-care/animal-poison-control/toxic-and-non-toxic-plants/geranium |

|

Plant name: Heavenly Bamboo

Scientific name: Nandina domestica Family: Berberidaceae Toxins: Cyanogenic glycosides Poisoning symptoms: Weakness, loss of coordination, seizures, coma, respiratory failure, hyperventilation, dyspnea (shortness of breath) tremors, bright or brick red mucous membranes, and possibly death (rare in pets). Indicative traits of cyanide poisoning include cherry-red blood and mucous membranes, and for those that can detect it, the smell of bitter almonds is also very characteristic. Additional information: Cyanogenic glycosides are a natural plant self defense mechanism found in a percentage of ferns and higher plant species designed to harm or dissuade animals from eating them. These are amino acid derived compounds linked to a glucose molecule and stored as an inactive toxin in specialized subunits within the plant cells, called vacoule. When animals damage plant leaves these enclosed cellular compartments release cyanogenic glucosides which then come into contact with enzymes in the plant called ?-glucosidases. This removes the glucose molecule leaving cyanohydrin; a chemically unstable amino acid derived compound that will further degrade spontaneously or by the action of an hydroxynitrile lyase to produce toxic hydrogen cyanide gas (HCN). Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is a highly toxic volatile compound that interferes with the cellular respiration by inhibiting the cytochrome oxidase enzyme in mitochondria. This prevents the production of ATP (adenosine-5'-triphosphate), the molecule that transfers energy in the cell. Luckily plant related cyanide poisoning in pets is extremely uncommon as the bitter taste of cyanogenic glucosides tend to limit the amount of plant that the pet can tolerate consuming. Of the 3000 species of plant known to produce cyanogenic glucosides the most common ones that pets come into contact with are pitted fruits such as peaches, cherries and almonds; pome fruits such as apples and pears; legumes such as clover and vetch; elderberry; and a variety of grasses. Of these the greatest risk would be posed by the pits or seeds of pitted or pome fruits which a pet may ingest out of curiosity leading to a rapid ingestion of a toxic dose. Source: http://www.pawsdogdaycare.com/heavenly-bamboo-poisonous-pets |

|

Description: Poison hemlock is a coarse biennial herb with a smooth, purple-spotted, hollow stem and leaves like parsley. It grows 3 to 6 feet tall and in late summer has many small white flowers in showy umbels. Its leaves are extremely nauseating when tasted. Although sometimes confused with water hemlock, poison hemlock can be distinguished by its leaves and its roots. The leaf veins of the poison hemlock run to the tips of the teeth; those of the water hemlock run to the notches between the teeth. The poison hemlock root is long, white, and fleshy. It is usually unbranched and can be easily distinguished from the root of water hemlock, which is made up of several tubers.

Conditions of poisoning: Animals allowed to graze pastures infested with this plant are most likely to be poisoned in early spring, when tender and succulent new leaves come from the root. Similar regrowth takes place in the early autumn. The root itself seems to be nearly harmless in spring, but later in the year all parts - roots, stem, leaves, and fruit - become extremely poisonous. It was the juice of poison hemlock with which the ancient Greeks killed Socrates. Many cases of human poisoning occur because the hemlock roots are mistaken for parsnips; the leaves, for parsley; and the roots and seeds, for anise. Control: Poison hemlock should be dug up and completely destroyed because it is dangerous to both animals and humans. Toxic principle: Piperidine (nicotinic) alkaloids in Conium include coniceine, coniine, N-methyl coniine, conhydrine, and pseudoconhydrine. The alkaloid content is variable with the stage of development and the stage of reproduction of the plant. During the first year of growth, the plant alkaloid content tends to be low. Plants in the second year, however, have alkaloid contents of approximately 1% in all plant parts. The alkaloid content is somewhat higher after sunny weather, as compared to rainy weather. The highest concentration of alkaloids occur in the seeds which can contaminate cereal grains. Coniine (2-propylpiperidine) and N-methyl coniine progressively increase in flowers and fruits, while coniceine decreases during plant maturation. In the vegetative stage - i.e. early growth - coniceine (W'-2 propylpiperidine) is the predominant alkaloid. Coniceine and coniine are the primary teratogenic alkaloids of Conium. Clinical signs: Susceptible species include cattle, pigs, elk, poultry, goat, sheep, and rabbit to some extent. Toxicosis has been experimentally reproduced in sheep and horses as well. Systemic effects: After having eaten poison hemlock, animals may lose their appetites, salivate excessively, bloat, and have a rapid but feeble pulse. They also show evidence of muscular incoordination and appear to have great abdominal pain. Other signs include muscle tremors, frequent urination and defecation, recumbency, mydriasis, and "nervousness" followed by severe depression. In animals that die, breathing ceases due to respiratory paralysis before cardiac arrest. Convulsions, which occur in water-hemlock poisoning, do not follow the eating of poison hemlock. |

|

Common Names and Synonyms: Irish ivy, common ivy.

How Poisonous, How Harmful? Contains saponins, digestion of which results in hydrolysis and production of toxic substances. Ingestion has emetic and purgative effects and is reported to cause laboured breathing, convulsions and coma. Not recently reported to have caused poisoning as its potential harm is well understood. The Auckland Regional Council, says that dust from Ivy can lead to sneezing and eye irritation. For that reason, many people say it should not be brought into the house. Incidents: The last known case of poisoning by ingestion was in the first quarter of the 20th century but there are a number of reported cases of skin irritation from handling the plant and, as a result, a number of papers have been written about its effects on the skin. A couple of cases of breathing difficulties, one requiring hospital admission, have also been mentioned. Source: http://www.thepoisongarden.co.uk//hedera |

|

Jerusalem Cherry/Nightshade

Description: About 1,500 Solanum species exist in the world, and they include some of the most common garden plants such as potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). One of the species, Jerusalem cherry (Solanum pseudocapcicum L.) is grown as a house plant for its compact form and small round berries which turn bright red at maturity. The tomato (Lycopercison esculentum Mill.) is also a related plant. Included in this entry are descriptions of Black Nightshade, Bittersweet Nightshade, Silverleaf Nightshade, and Horse Nettle. Other related species may be found under their own names. Conditions of poisoning: Poisoning by these Solanum species occurs primarily when animals are confined in overgrazed fields or where nightshade is abundant. The hazard of poisoning varies depending on the plant species, maturity of plants, and other conditions. Generally, the leaves and green fruits are toxic. Ingestion of juice from wilted leaves may be especially toxic and sometimes deadly. Many cases of poisoning have been reported as a result of eating green berries. Green berries have produced severe intestinal, oral and esophageal lesions in sheep. Cattle reportedly seek out the berries of Solanum species and will eat the green plant, specially when other green forage is unavailable. Silverleaf nightshade (S. eleagnifolium) is exceptional in that the ripe fruit is more toxic than the green. S. eleagnifolium is toxic at only 0.1% of the body weight. Toxicity is not lost upon drying. Solanine content increases up to maturity. Solanine, except in potatoes, is reportedly destroyed by cooking. Potato (S. tuberosum) peelings contain the major portion of the toxic principle in the tuber, and leaves, sprouts and vines. Sun-greened potatoes are especially toxic. Spoiled potatoes and peelings also have caused severe poisoning. Cooking does not appear to destroy all the alkaloids in greened potatoes. Toxicity may vary with the soil, climate and other variables. Animals may browse potato plants or eat sprouted potatoes, leading to problems. Control: Animals should be kept away from fields with heavy infestation of nightshade. Plants should be mowed or pulled up while in flower, and burned. Remove green parts of potatoes before cooking, eat only ripe tubers. Toxic principle:

Clinical signs: Vary with irritant effect caused by the intact glycoalkaloid or saponin, and the nervous effects of the alkaloid. Irritant effects include hypersalivation, anorexia, severe gastrointestinal disturbances, with diarrhea that is often early and hemorrhagic. The nervous effects include apathy, drowsiness, depression, confusion, progressive muscular weakness, numbness, dilated pupils, trembling, labored breathing, nasal discharge, rapid heartbeat, weak pulse, bradycardia, central nervous system depression, and incoordination, often accompanied by paralysis of the rear legs. Coma may occur without other nervous signs. High doses may cause intestinal stasis and constipation. Hemolysis and anemia, possibly a result of saponins, have been reported, with renal failure in severe cases. Terminal signs include unconsciousness, shock, paralysis, coma, circulatory and respiratory depression, and death. The course varies from sudden death to 3-4 days of illness which may terminate in death or recovery. in less acutely poisoned animals, there may be yellow discoloration of the skin in unpigmented areas, weakness, incoordination, tremors of the rear legs, anemia, rapid heart rate and bloat. Source: http://www.library.illinois.edu/vex/toxic/nightshade/japcherry |

|

Lantana flowers initially cream, yellow or pink changing to orange or scarlet, thus resulting in a multi-colored, short, headlike spike. Fruit greenish blue or black, one seeded. Found in sandy Coastal Plain soils, Florida to Texas; common along roadsides and in waste places, yards, and gardens; persisting after cultivation and escaping.

Toxicity: This ornamental shrub contains lantanin, a triterpenoid, and other compounds irritat- ing to the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract. All parts of the plant are quite toxic, and poisoning may occur year-round but is most common in summer and fall. Many poisoning cases occur when clippings are thrown into the pasture. Sheep, pigs, cattle, horses, and humans are sensitive to the effects of the plant. Cattle are most often affected. Children have been poisoned by eating the berries. Symptoms: There are two forms of toxicity: acute and chronic. The acute form usually occurs within 24 hours after the plants are eaten. Animals exhibit gastroenteritis with bloody, watery feces. Severe weakness and paralysis of the limbs are followed by death in 3 to 4 days. The chronic form is characterized by jaundiced mucous membranes, photosensitiza- tion, and ulcerations of the mucous membranes of the nose and oral cavity. The skin may peel, leaving raw areas that are vulnerable to blowfly strikes and bacterial infection. Severe keratitis may result in temporary or permanent blindness. Treatment: Remove animals from direct sunlight. Use antibiotic injections and topical applications of protective antibiotic creams. Treat with 20 percent sodium thiosulfate (1 ounce per 100 pounds); repeat treatment every other day. Use topical application of cortisone to relieve itching. Source: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs |

|

Larkspur (Delphinium spp.)

Larkspurs are characterized by palmately (spreading like the fingers of a hand) lobed or divided leaves and slender spikes of purple or blue (sometimes white to pink or lavender) trumpet-shaped flowers with a prominent spur at one end. Tall larkspurs grow 3 to 7 feet tall and are found in moist places like stream sides, mountain meadows, and shaded ravines. Low larkspurs are less than 3 feet tall and are found in grassy hillsides and desert areas. Larkspurs grow in a number of plant communities in mountain and foothill ranges throughout the states and can cause significant losses of livestock. Horses, goats and sheep are susceptible but are rarely affected. All species of larkspur are considered poisonous, but the toxin concentrations depend on the species and the stage of growth. Most poisonings occur during the “toxic window,” the time when a specific larkspur plant is palatable and contains sufficient toxins to cause poisoning. Tall larkspurs are most toxic from the flowering period until the seedpods have matured. Low larkspurs are highly toxic and palatable early in the spring. Dried plants remain toxic. Signs of poisoning and treatment: The toxins in larkspurs have a curare-like action that result in loss of motor function (especially in the diaphragm and esophagus), muscle weakness, and paralysis. Cattle are most susceptible, while sheep can tolerate about 4 to 5 times the amount that is fatal to cattle. Cattle are often found dead 3 to 4 hours after exposure. If clinical signs are observed, they include staggering and sudden falling, bloat, and respiratory distress. Do not stress poisoned animals. Because cattle will eat larkspur even when other forage is present, extensive stands of larkspur are cause for concern. Pigs are unknown if they're affected. Treatment of affected animals is useful only if a rapid diagnosis is made. Fencing affected areas, hand-grubbing localized patches, and spraying more widespread stands with herbicides can be appropriate measures, depending on local range conditions. Exposure of cattle to larkspurs during the “toxic window” must be avoided to effectively prevent poisoning. Sheep can be considered for biological control. Source: http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8398.pdf |

|

Pulse or Pea Family (Leguminosae) Licorice Plant

Description: Moderate-sized tree, often with 2 short spines at base of leafstalk, bark rough. Leaves alternate, pinnately compound; the individual leaflets oval-shaped, without teeth. Flowers creamy white, fragrant, sweet-pea like, arranged in long, drooping,.clusters. Fruit a flat, brown pod, 1/2 inch wide, 2 to 4 inches long, and containing 4-8 small kidney-shaped beans. Common in woods and thickets. Often planted as an ornamental and for erosion control, but has spread widely as a "weed" tree along highways and in waste places. Conditions of poisoning: The poisonous substance is a phytotoxin, robin. Animals are affected by eating the young shoots, leaves, pods, seeds, and by gnawing on the bark, or drinking water in which the pods have been soaked. All farm animals are susceptible. Symptoms: Animals will become stupid, not notice their surroundings, and stand with the legs apart. Heart action is irregular and breathing is feeble, mucous membranes are yellow, and the pupil of the eye dilated. Colic pains may be present and soon followed by diarrhea. Cattle are quite often dizzy and very nervous. For other animals, impaction is a risk from eating the peas from the flowering plant. Treatment: Death follows the onset of symptoms unless treatment is started soon. An injection of digitalis to help the heart action is useful. Other treatments used are just to help decrease the symptoms and give ease to the animal. Source: http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs |

|

A Little About the Common Cocklebur: Xanthium strumarium is the Common Cocklebur, this is an annual weed with an irregular, mottled stem, thick leaves, small flowers which grow on short branches and the fruit is a burr with hooked spines.

How Dangerous Is It? This plant is obviously something most grazers won’t mess with, not only is it unpalatable, but it’s got huge thorns! Really only a concern during a seriously difficult drought season, but one to know about anyway. Cockleburs contain carboxyatractyloside which affects the nervous system. All parts of the plant are toxic (with the highest concentration in the seeds) to animals. Source: http://www.theequinest.com/cockleburr |

|

Cardinal flower/Indian tobacco/Lobelia

Lobelia spp; leaves, stems, fruit; nervous system affected by pyridine, a nicotine-like toxin; plant also causes dermatitis. Source: http://www.zutrition.com/reptiles-and-harmful-plants/ |

|

Lupines (Lupinus spp.); leaves, esp. seeds; plant contains numerous alkaloid toxins including quinolizidine and piperidine.

Source: http://www.zutrition.com/reptiles-and-harmful-plants/ |

|

About Milkvetch

Growth Characteristics: An erect to prostrate forb, with stems that are mostly hairy and leafy. Milkvetches emerge from late April to June and reproduce from seed. Flowers/Inflorescence: Flowers resemble pea flowers but are smaller. Colors vary from white to yellow to blue to purple, and are arranged in a raceme. Fruits/Seeds: A pea pod (legume) with a papery, leathery, or woody cover. Leaves: Odd-pinnate leaves (a leaflet at the terminal end of the leaf), usually pubescent. Where and When It Grows Milkvetches grow throughout much of the North American continent. Most of the poisonous species grow on the meadows, deserts, and forests in the Rocky Mountain states. Milkvetches emerge from late April to June, depending on elevation and snow melt. Leaves and stems become dry after seed dispersal in July or August. Plants are poisonous from the time they emerge until they dry up or are killed by frost. Poisonous nitro compounds are found in varying quantities in 263 species and varieties of North American Astragalus. How It Affects Livestock Milkvetches are poisonous plants that affect cattle, sheep, and horses. Cattle of all ages are highly susceptible to poisoning. Even when other forage is available, cattle readily eat milkvetch. Milkvetch poisoning may be mistaken for larkspur poisoning. Unknown if it affects pigs the same way is does other species of animals. The poison in milkvetches acts quickly. Two pounds of green milkvetch may cause acute poisoning or death in a 1,000-pound cow. Some deaths occur within one hour, so fast that cattle show no signs; more often, animals die within three or four hours after eating the plant. Acute poisoning is characterized by a general muscular weakness. It paralyzes leg muscles so that affected animals fall after the slightest excitement, although they appear bright. The heart beats very rapidly before the animal dies from heart failure. Chronic intoxication may occur from grazing any of the toxic milkvetch species slowly over a period of several days or weeks. This type of intoxication is characterized by respiratory problems and varying degrees of posterior paralysis. This condition occurs in most of the western United States and western Canada. How to Reduce Losses To reduce losses, prevent animals from grazing these plants for extended periods.There is no known treatment for milkvetch poisoning. Source: http://articles.extension.org/pages/milkvetch |

|

Mountain Laurel

Large, densely branched shrub or small tree up to 5 m tall. Leaves thick, leathery, evergreen, mostly alternate or in whorls of threes, elliptical, 8 to 15 cm long, 1.5 to 5 cm wide; margins entire and rolled in. Flowers white to pink, 2 to 3 cm in diameter, in large showy clusters. Found in all the southern states but less common in the Coastal Plain; most common on dry, rocky slopes and ridges and in open woods. [Inset: flower of K. hirsuta (wicky), a com- mon shrub, mostly of the lower Coastal Plain, more common than sheep laurel] Sheep laurel Kalmia angustifolia Very similar to mountain laurel and also toxic. Shrub to 1.5 m tall. Usually a smaller plant than K.‐latifolia with narrower and smaller leaves and smaller flowers that are more often pink than white. This species usually occupies wetter sites and is limited mostly to mountainous areas of Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia. Toxicity: The resinoid andromedotoxin and the glucoside arbutin are the toxic principles respon- sible for symptoms. Sheep, goats, and cattle are susceptible to poisoning if they eat the plant, especially the leaves. There are recorded cases of toxicity in humans and monkeys. Most clinical cases of laurel toxicity are seen in the winter and early spring months. When other forage is not available, livestock may consume the toxic evergreen laurels. Symptoms: Signs of toxicity occur usually within 6 hours after the plants are eaten. Symptoms include incoordination, excessive salivation, vomiting, bloat, weakness, muscular spasms, coma, and death. The animals are often found down, unable to stand, with their heads weaving from side to side. Treatment: In severe cases, do not drench animals or give medicine by mouth since they may be unable to swallow due to weakness of the throat muscles. Administer mineral oil or saline laxatives by stomach tube. Give intravenous electrolyte solutions. Source: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs/ |

|

Narcissus (Daffodil, Jonquil, Paper White)

Scientific Names: Narcissus spp Family: Amaryllidaceae Toxicity: bulbs Effect: gastrointestinal tract affected by alkaloid toxins; plant also causes dermatitis. Source: http://www.aspca.org/pet-care/animal-poison-control/-plant-list |

|

Oleander (Nerium oleander, other species)

Effects: cardiovascular system affected by the glycosides oleandrin, oleandroside, and nerioside; plant also causes dermatitis. Toxicity: The toxic principles are two glycosides, oleandroside and nerioside, which can be isolated from all parts of the plant. Toxins may also be inhaled in smoke when plants are burned. Human poisoning occasionally occurs from eating hot dogs roasted on sticks from nearby oleander plants. This extremely toxic plant can poison livestock and humans at any time of the year. Entire plant, and water used for cut plants is the toxic portions of this plant. Symptoms: Severe gastroenteritis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, sweating, and weakness are the usual symptoms. These signs appear within a few hours after eating the leaves. Cardiac irregularities are common, often characterized by increased heart rate. However, a slower heart rate is often detected in the later stages. Treatment: Nonspecific. Treat symptoms although symptomatic treatment is usually unsuccessful. Sources: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs |

|

Pokeweed

Perennial herb, to 3 m tall, often with many stems from large fleshy rootstock. Stems green to purplish, fleshy, smooth. Leaves alter- nate, light green, lanceolate, 8 to 30 cm long, 3 to 12 cm wide, glabrous, margins en- tire. Flowers white to purplish in drooping axillary racemes. Ripe fruit black, juicy, many seeded, when mashed pro- duces a red “ink.” Distributed throughout the South; most common on waste ground, fence rows, pasture, and old homesites. Young leaves often used as a cooked green vegetable; older leaves are quite poisonous. Toxicity The poisonous principles are oxalic acid and a saponin called phytolaccotoxin. In addition, alkaloids may be present. The root of the plant is the most toxic portion, but all other parts of the plant contain smaller amounts of the toxic principles. Cattle, horses, swine, and humans have all been poisoned after consuming this plant. Recognizable clini- cal cases are rare, however. Swine are most often affected since they grub up the roots. Poisoning occurs during spring, summer, or fall. In the springtime people commonly cook the leaves and consume them. This “poke salad” is generally safe if the water in which the leaves are cooked is poured off. Symptoms The most common symptom is a severe gastroenteritis with cramping, diarrhea, and convulsions. Postmortem lesions include severe ulcerative gastritis, mucosal hemorrhage, and a dark liver. In most cases the animal recovers within 24 to 48 hours. Treatment Give gastrointestinal protectives such as mineral oil or various clays. Administer tannic acid and sedatives; a specific antidote is dilute vinegar. Provide respiratory stimulants. |

Source: http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs

|

|

Redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus L.) may be lethal to pigs.

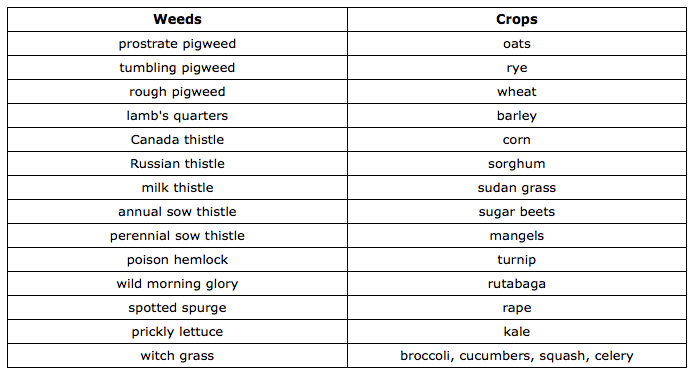

Pigweed is a major agricultural weed throughout the US; fence rows, farm yards and empty livestock lots tend to have luxurious pigweed growth, especially during warm months. A distinct health problem known as "perirenal edema" may affect hogs, and sometimes cattle, following ingestion of sufficient quantities of the weed. The term "perirenal edema" describes the ap pearance of the kidneys and tissues surrounding them in pigs victims of pigweed poisoning. The whole plant is toxic to pigs. Source: http://library.ndsu.edu/tools/pigweeds Nitrate Accumulators A number of common crop and pasture plants and weeds can accumulate toxic concentrations of nitrate. Among the weeds, pigweeds (Amaranthus spp.), lambsquarter or goosefoots (Chenopodium spp.), and nightshades (Solanum spp.) have been found to contain nitrate at potentially toxic concentrations. Among crop plants, oat hay, corn, and sorghum have especially been associated with nitrate toxicosis, and alfalfa can also contain potentially toxic nitrate concentrations. Conditions such as heavy fertilization of pastures, herbicide application, drought, cloudy weather, and decreased temperature yield increased concentrations of nitrate in plants. In addition, nitrate accumulates in the vegetative tissue, creating the highest concentrations in the lower stalks and stems. Leaf material and grain or seeds generally do not contain toxic nitrate levels. Forage nitrate levels of 0.3 percent (3,000 ppm) and above are potentially dangerous, with acute poisoning likely to occur if the nitrate level exceeds 1 percent (10,000 ppm). |

|

Privet

Additional Common Names: amur, wax-leaf, common privet Scientific Name: Ligustrum japonicum Family: Oleaceae Toxicity: Toxic to Dogs, Toxic to Cats, Toxic to Horses, presumed to be toxic to pigs as well. Toxic Principles: Terpenoid glycosides Clinical Signs: Gastrointestinal upset (most common), incoordination, increased heart rate, death (rare). Source: http://www.aspca.org/pet-care/animal-poison-control/toxic-and-non-toxic-plants/privet |

|

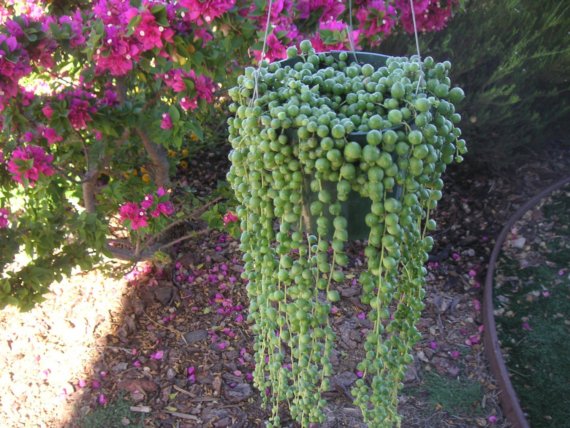

String of Pearls

In humans, string of pearls is rated as toxicity classes 2 and 4 by the University of California, Davis. Class 2 means minor toxicity; ingestion of string of pearls may cause minor illness like vomiting or diarrhea. Class 4 means dermatitis; contact with the plant's juice or sap may cause skin irritation or rash. If your child ingests string of pearls, call the Poison Control Center or your child's pediatrician immediately. In pets, including cats and dogs, possible symptoms of ingestion of the string of pearls plant may be: drooling, diarrhea, vomiting or lethargy. Some may suffer irritation to the skin or mouth due to contact. Contact your veterinarian immediately if you believe your pet has ingested this plant. So it hasn't been proven to be "extremely toxic" to pigs. Source: http://homeguides.gate.com/poisonous-string-pearl-plants |

|

Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia)

Toyon is also known as tollon, Christmas holly, or Christmas berry. The plant is a native evergreen shrub or tree with bright red fruit in the winter. Although it is native to California and Baja California, toyon is also widely planted as an ornamental. Its natural habitat includes chaparral, oak and conifer woodlands, and mixed-evergreen forests up to 3,300 feet elevation. The plant is also used as a Christmas decoration. Signs of poisoning and treatment The toxic compounds in toyon are the same as those in arrowgrass, thus the signs and treatment are identical. Toyon poisoning has killed goats that were offered fresh clippings. In order to prevent toyon poisoning, animals should not be offered toyon clippings or have access to toyon in their environment. Source: http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu |

|

Summer Pheasant’s Eye (Adonis aestivalis)

Summer pheasant’s eye is a plant in the buttercup family that was introduced into North America as a horticultural plant but escaped cultivation and is now naturalized in the western United States. It is well established in some Northern California counties and has been found as a contaminant in alfalfa and grass hay. The stems of summer pheasant’s eye have linear ridges, the leaves are feathery, and the flowers have waxy, orange petals. Summer pheasant’s eye is considered unpalatable, which is most likely why reports of poisoning are rare. Signs of poisoning and treatment The toxins in summer pheasant’s eye and the signs of poisoning are similar to those of oleander. Leaves and flowers have the highest concentrations of toxins. In addition to cardiac toxicity, horses poisoned with summer pheasant’s eye develop gastrointestinal disturbances such as colic, hemorrhagic enteritis, diarrhea, or decreased gut mobility. Source: http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf |

|

Alternate names: Liliaceae, tulips, hyacinths

Both hyacinths and tulips belong to the Liliaceae family, and contain allergenic lactones or similar alkaloids. The toxic principle of these plants is very concentrated in the bulbs (versus the leaf or flower), and when ingested in large amounts, can result in severe clinical signs. Severe poisoning from hyacinth or tulip poisoning is often seen when dogs dig up freshly planted bulbs or having access to a large bag of them. When the plant parts or bulbs are chewed or ingested, it can result in tissue irritation to the mouth and esophagus. Typical signs include profuse drooling, vomiting, or even diarrhea, depending on the amount consumed. With large ingestions, more severe symptoms such as an increase in heart rate, changes in respiration, and difficulty breathing may be seen. Poison type: Plants Scientific name: Tulipa gesneriana; Hyacinthus spp. Level of toxicity: Generally mild to moderate Common signs to watch for:

Source: http://www.petpoisonhelpline.com/poison/tulip |

|

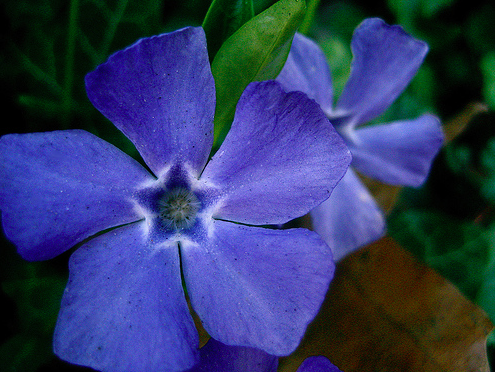

Plant name: Blue Periwinkle

Scientific name: Vinca major Family: Apocynaceae Toxins: Vinca Alkaloids; vindoline, vincadifformine, vincaleukoblastine (vinblastine), 22 - oxovincaleukoblastine (vineristine), reserpine, perivincine, vincamine, akuammine, alstonine, leurocristine, ajmalicine, vinine, vinomine, vinoxine, vintsine, leurosine Poisoning symptoms: Gastrointestinal upset (vomiting & diarrhea), hypotension (low blood pressure), possible cardiac abnormalities, depression, tremors, seizures, progressive paralysis, coma, death. Serious intoxication of animals is exceedingly rare and fatal intoxications rarer yet. Additional information: Vinca major, more commonly known as Bigleaf Periwinkle, Large Periwinkle, Greater Periwinkle and Blue Periwinkle is an evergreen trailing vine that spreads along the ground, rooting at the nodes to form dense masses of groundcover. Vinca major is noted for being an extremely fast growing plant, so much so that a single specimen can cover an area 15’ or more with a dense carpet of shiny dark green foliage in just a couple of months. The leaves are 2-3 inches long, oval or heart shaped and grow in pairs opposite each other along the length of the stem. The flowers, borne singly in the leaf axils on ascending stems are blue-violet, funnel shaped with five petals and about 2 inches across. Big periwinkle flowers heavily throughout the spring and sporadically during the summer. Information regarding the specific toxicity of Vinca major varies from source to source, although all sources agree that the plants contain an extensive array of alkaloids. They also contain saponins and various other compounds. The alkaloid content also seems to vary from region to region, especially between areas where they grow as annuals rather than perennials. Of the more than 130 compounds found in vinca major, the principal components include vindoline, vincamine and vincadifformine. Many of the alkaloids, including akuammine, perivincine, reserpinine, and vinine, are hypotensive, although to what extent is not fully understood. When ingested the overall effect of these compounds is a reduction in blood pressure and in exceptionally large doses possible systematic paralysis and death. It should be noted that large ingestions of vinca major are extremely rare; most animals consider the plant to be unpalatable. Source: http://www.pawsdogdaycare.com/toxic-and-non-toxic-plants/blue-periwinkle |

|

Wintergreen

Concerns: Toxicity: Methyl salicylate is an organic ester found in a number of plants such as Wintergreen, Birch, and Meadowsweet. It is similar in structure to salicylic acid, the active ingredient in aspirin. Oil of Wintergreen is a highly concentrated form of methyl salicylate. It is reported that 10 milliliters is a fatal dose in a child, and 30 mL will kill an adult; however, there ahve been fatalities with as little as 4 mL (that is just over a teaspoon!). As the methyl salicylate can be absorbed through the skin, even topical use can be dangerous. With all that said, we need to be very careful about when, why, and how we use this essential oil. Source: http://tcpermaculture.com/site/2014/01/22/permaculture-plants-wintergreen |

|

Wisteria

Scientific Name: wisteria species Family: Fabaceae Toxicity: Toxic to Dogs, Toxic to Cats, Toxic to Horses, Presumed to be toxic to pigs Toxic Principles: Lectin, wisterin glycoside Clinical Signs: Vomiting (sometimes with blood), diarrhea, depression Source: http://www.aspca.org/pet-care/animal-poison-control/toxic-and-non-toxic-plants/wisteria |

|

Yew

History and General Information

|

Common Poisonous Plants in the Home, Yard, and Garden

Classification of Poisons

There is a large variety of toxic substances that have been associated with plant poisonings. Unfortunately for many plant species, the nature of the toxic substance has not yet been identified. However, most of the important poisonous plants contain toxic agents from one or more of the following groups.

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are organic basic substances with a bitter taste, examples of which are morphine, atropine, nicotine, quinine and strychnine. The alkaloids generally are irritating to the gastrointestinal tract producing nausea, colic and diarrhea and also act on the central nervous system to produce blindness, muscular weakness, convulsions and death. Toxic alkaloids are found in the following plants; swamp and death camas, lupines, buttercups, marshmarigolds, larkspur, the nightshades, squirrel corn and Dutchman's breeches.

Glycosides

Glycosides are natural plant products that contain the sugar glucose. They can be subdivided into three main groups.

There are many factors that influence the amount of cyanogenic glycosides in plants. Some plant species normally have high levels, the highest levels occurring in early growth stages and decreasing as the plants mature. Climatic conditions, soil factors, shade and other factors that slow plant growth and development increase cyanogenic glycoside content. Low soil moisture, high nitrogen and low phosphorus all favor HCN production. Wilting, frost and other forms of physical damage to plants may induce a rapid increase in HCN content.

Cyanogenic glycosides occur in sorghums, sudan grass, marsh-arrow grass and wild cherries.

Nitrate

Nitrate poisoning of animals is actually nitrite poisoning occurring when nitrate is reduced to nitrite in the gastrointestinal tract. The nitrite is absorbed into the bloodstream where it reacts with hemoglobin to form methemoglobin. This compound, which is brown in color, is incapable of releasing oxygen. In acute cases of poisoning in cattle, 60 to 80% of the total hemoglobin is comprised of methemoglobin. Sheep generally do not develop as much methemoglobin and are therefore more resistant to this form of poisoning.

The symptoms of acute poisoning are trembling, staggering, rapid breathing, and death. Chronic poisoning may result in poor growth, poor milk production and abortions. In cattle, there is evidence that vitamin A storage is affected.

Some plant species are naturally good accumulators of nitrates. The legume and grass species that are used for pastures or hay crops are not considered good nitrate accumulators, but given the right conditions can accumulate concentrations of nitrate that are potentially hazardous.

There is a direct response in plant nitrate concentration to increasing levels of nitrogen fertilization. Nitrate accumulation is greater when nitrate fertilizers are used than when either urea or ammonium sulfate is the nitrogen source.

A number of environmental conditions can influence the accumulation of nitrates in plants by altering mineral metabolism in the plant. Drought, uneven distribution of rainfall, and low light intensity have each been identified as climatic factors that bring about an accumulation of nitrates and nitrites in the stems and leaves of plants.

There is a large variety of toxic substances that have been associated with plant poisonings. Unfortunately for many plant species, the nature of the toxic substance has not yet been identified. However, most of the important poisonous plants contain toxic agents from one or more of the following groups.

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are organic basic substances with a bitter taste, examples of which are morphine, atropine, nicotine, quinine and strychnine. The alkaloids generally are irritating to the gastrointestinal tract producing nausea, colic and diarrhea and also act on the central nervous system to produce blindness, muscular weakness, convulsions and death. Toxic alkaloids are found in the following plants; swamp and death camas, lupines, buttercups, marshmarigolds, larkspur, the nightshades, squirrel corn and Dutchman's breeches.

Glycosides

Glycosides are natural plant products that contain the sugar glucose. They can be subdivided into three main groups.

- Cyanogenic glycosides

There are many factors that influence the amount of cyanogenic glycosides in plants. Some plant species normally have high levels, the highest levels occurring in early growth stages and decreasing as the plants mature. Climatic conditions, soil factors, shade and other factors that slow plant growth and development increase cyanogenic glycoside content. Low soil moisture, high nitrogen and low phosphorus all favor HCN production. Wilting, frost and other forms of physical damage to plants may induce a rapid increase in HCN content.

Cyanogenic glycosides occur in sorghums, sudan grass, marsh-arrow grass and wild cherries.

- Saponin glycosides

- Mustard oil glucosides

Nitrate

Nitrate poisoning of animals is actually nitrite poisoning occurring when nitrate is reduced to nitrite in the gastrointestinal tract. The nitrite is absorbed into the bloodstream where it reacts with hemoglobin to form methemoglobin. This compound, which is brown in color, is incapable of releasing oxygen. In acute cases of poisoning in cattle, 60 to 80% of the total hemoglobin is comprised of methemoglobin. Sheep generally do not develop as much methemoglobin and are therefore more resistant to this form of poisoning.

The symptoms of acute poisoning are trembling, staggering, rapid breathing, and death. Chronic poisoning may result in poor growth, poor milk production and abortions. In cattle, there is evidence that vitamin A storage is affected.

Some plant species are naturally good accumulators of nitrates. The legume and grass species that are used for pastures or hay crops are not considered good nitrate accumulators, but given the right conditions can accumulate concentrations of nitrate that are potentially hazardous.

There is a direct response in plant nitrate concentration to increasing levels of nitrogen fertilization. Nitrate accumulation is greater when nitrate fertilizers are used than when either urea or ammonium sulfate is the nitrogen source.

A number of environmental conditions can influence the accumulation of nitrates in plants by altering mineral metabolism in the plant. Drought, uneven distribution of rainfall, and low light intensity have each been identified as climatic factors that bring about an accumulation of nitrates and nitrites in the stems and leaves of plants.

Molybdenum

Molybdenum poisoning can occur when there are abnormally high quantities of molybdenum in the soil. Animals pasturing on areas that meet this condition are often subject to acute scouring. The animals become emaciated, produce less milk, and their coats become rough and often faded. Legumes, particularly red and alsike clovers, are usually associated with molybdenum poisoning. To counteract the effect of molybdenum, it is necessary to add copper to the diet of the animals. A veterinarian should be consulted first before feeding copper.

Copper

Copper may also accumulate in plants in amounts great enough to cause toxic effects if soils are rich in copper or deficient in molybdenum. Clovers are good accumulators of copper and are generally associated with copper poisoning. This is considered one of the chelating poisons.

Selenium

Selenium is a highly toxic element when taken in quantities larger than what is needed for normal metabolism. In most plants, the level of selenium is related to levels in the soil. The symptoms of selenium poisoning are: dullness, stiffness of joints, lameness, loss of hair from mane or tail and hoof deformities. The acute form of poisoning is often called "blind staggers".

Ergot

Ergot is a fungus that infests grasses and if eaten in sufficient quantities is poisonous due to the production of a mycotoxin. Ergot's presence is observed by hard, dark-colored masses in flowering grass heads. These purplish or dark brown masses are usually two to five times larger than the grass seed and are called ergot bodies.