Can I get sick from my mini pig?

Zoonotic Diseases

What does zoonotic disease mean?

A zoonosis is any disease or infection that is naturally transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans. Animals thus play an essential role in maintaining zoonotic infections in nature. Zoonoses may be bacterial, viral, or parasitic, or may involve unconventional agents. As well as being a public health problem, many of the major zoonotic diseases prevent the efficient production of food of animal origin and create obstacles to international trade in animal products. There are a lot of different illnesses and diseases all over the world, only some can be passed from person to pig and pig to person. Keep in mind that pigs excrete 3000 times more virus particles than other "farm animals", so if there is a possibility, you should take proper precautions to avoid exposure.

Transmission

For diseases to be transmitted from pigs to people the causative organism (pathogen) must be ingested, inoculated, or inhaled. Knowing this presents a clear opportunity to prevent infection. For example, if people washed their hands before handling food or touching their mouths, the likelihood of accidentally ingesting any pathogen, e.g., Salmonella, Toxoplasma, or Campylobacter, would drop dramatically. Factors that will increase the susceptibility of individual workers include stress, fatigue, poor general health, pregnancy, immunosuppression, and age. Your illness DOES have the potential to be passed along to your pig and vice-versa. Depending on the agent, you can get your pig sick or your pig can get you sick. Be familiar with the bacterias and virus's listed, so you will know if you have a sickness that can be passed on to your pet pig.

Bacteria

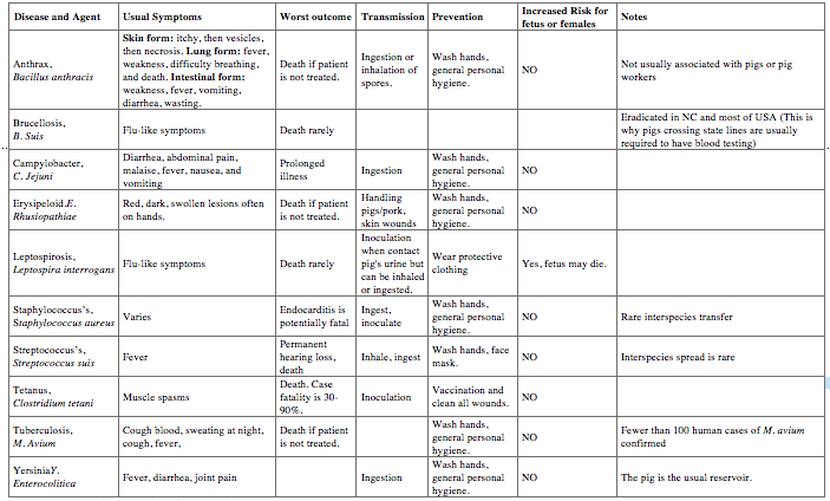

Bacteria are single-celled organisms with cell walls. They are characterized by shape as cocci, bacilli and spirilla and differentiated based on gram stain and other biochemical tests. They are usually considered to be either gram positive or gram negative. See chart below.

A zoonosis is any disease or infection that is naturally transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans. Animals thus play an essential role in maintaining zoonotic infections in nature. Zoonoses may be bacterial, viral, or parasitic, or may involve unconventional agents. As well as being a public health problem, many of the major zoonotic diseases prevent the efficient production of food of animal origin and create obstacles to international trade in animal products. There are a lot of different illnesses and diseases all over the world, only some can be passed from person to pig and pig to person. Keep in mind that pigs excrete 3000 times more virus particles than other "farm animals", so if there is a possibility, you should take proper precautions to avoid exposure.

Transmission

For diseases to be transmitted from pigs to people the causative organism (pathogen) must be ingested, inoculated, or inhaled. Knowing this presents a clear opportunity to prevent infection. For example, if people washed their hands before handling food or touching their mouths, the likelihood of accidentally ingesting any pathogen, e.g., Salmonella, Toxoplasma, or Campylobacter, would drop dramatically. Factors that will increase the susceptibility of individual workers include stress, fatigue, poor general health, pregnancy, immunosuppression, and age. Your illness DOES have the potential to be passed along to your pig and vice-versa. Depending on the agent, you can get your pig sick or your pig can get you sick. Be familiar with the bacterias and virus's listed, so you will know if you have a sickness that can be passed on to your pet pig.

- Ingestion: Many, if not most, of the zoonotic diseases for pig farmers are acquired by eating the infectious organism. Breaking the fecal-oral cycle depends on simple personal hygiene. At work, you should always wash your hands before eating, smoking, or touching your mouth.

- Inoculation: Tetanus is the most serious disease for pig farmers that is transmitted by inoculation. Every farm worker should be vaccinated for tetanus.

- Inhalation: Although the inhalation of dust and other matter can be a health hazard it is not the usual mode of transmission for zoonotic pathogens. The major exception is the transmission of Streptococcus suis. Because children can be severely affected by Streptococcus suis they should wear face masks when working with pigs. Fortunately, cases are rare.

Bacteria

Bacteria are single-celled organisms with cell walls. They are characterized by shape as cocci, bacilli and spirilla and differentiated based on gram stain and other biochemical tests. They are usually considered to be either gram positive or gram negative. See chart below.

Viruses

Viruses are classified depending on how they look under a microscope, their outer shell, and the type of genetic material (RNA or DNA). Viruses cannot multiply outside the host cell. Outside the host they can live for only a few hours to a few weeks.

Nipah: This newly identified virus has killed about 103 people in Malaysia. The epidemic started in 1997 with an outbreak of encephalitis among pig-farm workers in the state of Perak in Malaysia. The virus, which is transmitted from pigs to humans, swept through more than half of Malaysia's thirteen states. By May 1999, the Malaysian Ministry of Health, in association with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, reported 258 cases of encephalitis in adults, with a case-fatality rate of almost 40%. Initially, the causative agent was thought to be Japanese encephalitis virus because that was common in the area. The abnormal (for JEV) clinical signs led researchers to search for another agent. They eventually identified another virus that they named Nipah after the Malaysian village where it claimed its first victim. To prevent its spread, the Malaysian government ordered the destruction of about 1 million pigs. The virus has been isolated from humans, pigs, dogs, cats, horses, goats and bats and it has basically ruined the pig-farming industry in most of Malaysia. Nipah virus has not been identified in the USA.

Menangle: This is a very rare virus and only one outbreak in New South Wales, Australia has been identified. It caused flu-like symptoms in people. It is also carried by fruit bats.

Influenza: The first thing to realize is that swine flu and human influenza (Spanish Flu which killed 20 million to 40 million people in 1918 and 1919) were not caused by the same virus--they had a common ancestor. However, the epithelial cells of pigs seem to have receptors for both human and avian influenza and that supports the idea that pigs may be the mixing vessel wherein human pathogens my develop. To keep on top of the situation public health officials should monitor human clinical flu outbreaks and determine which type is involved.

Hepatitis-E: HEV was experimentally reproduced in swine in Russia in 1990. Subsequently, studies by US and Nepalese investigators in the Kathmandu Valley found that 33% of pigs had evidence of past or current infection. About 9% of pig workers had antibodies to the virus. Work in the USA seems to indicate that swine HEV is genetically very distinct from the HEV strains previously compared. It is very closely related to HEV US-1 and US-2. Indications are that swine HEV and the US human HEV strains together form a distinct branch. Experimentally, cross-species infection has been demonstrated for this new branch of HEV strains. Therefore, it is possible that swine-to-human HEV infection is occurring. HEV has the potential to infect people working with pigs. Results of recent sero-survey of large-animal veterinarians in the mid-west revealed that about 10% had antibodies to HE-these infections were probably entirely subclinical. The risk that HEV represents to people on hog farms, or the risk that it may be transmitted to their families or to other members of the community, is unknown. There are no data suggesting economic losses due to HEV infections in swine.

Encephalomyocarditis: (EMC) It is an RNA virus. It is rare in humans and not fatal.

Internal Parasites

Ascariasis: Caused by the worm Ascaris suum. Ingestion of the ova sets up a transient infection in humans. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene.

Balantidiasis: Caused by Balantidium coli. Humans are very resistant but swine are major source for humans. An infection is acquired by ingestion of the parasite. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene

Toxoplasmosis: Caused by Toxoplasma gondii. Workers can acquire an infection by eating pork containing cysts or ingesting the oocysts excreted by cats that live around the hog operation. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene and not eating undercooked pork.

Cryptosporidiosis: Caused by a coccidian protozoa, Cryptosporidium parvum, that causes diarrhea, vomiting, wasting, and abdominal pain. Some people may have no symptoms. In the worst cases it can cause severe prolonged diarrhea with wasting and death. It is transmitted through contaminated water and the directly through the fecal-oral route. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene.

Fungi

Ringworm: Caused by a variety of fungi. The commonest cause in swine is Microsporum nanum. In humans they cause scaly lesions with itching and hair loss. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene.

Mites

Scabies: In swine the organism is Sarcoptes scabiei var. suis which can live on people but not reproduce on them. In other words, humans are a dead-end host for the pig scabies mite.

Rabies

This needs to be included in the list of zoonotic diseases, but is often neglected when discussing diseases that can be spread from animal to person and vice-versa. Rabies is a zoonotic disease (a disease that is transmitted to humans from animals) that is caused by a virus. Rabies infects domestic and wild animals, and is spread to people through close contact with infected saliva (via bites or scratches) There have been cases of pigs who tested positive for rabies. There is not a pig approved vaccination, but many vets use the rabies vaccine off label to protect pet pigs from any exposure.

Symptoms: The first symptoms of rabies are flu-like, including fever, headache and fatigue, and then progress to involve the respiratory, gastrointestinal and/or central nervous systems. In the critical stage, signs of hyperactivity (furious rabies) or paralysis (dumb rabies) dominate. In both furious and dumb rabies, some paralysis eventually progresses to complete paralysis, followed by coma and death in all cases, usually due to breathing failure. Once symptoms of the disease develop, rabies is fatal. Without intensive care, death occurs during the first seven days of illness.

Treatment after exposure: Recommended treatment to prevent rabies depends on the category of the contact:

• Category I: touching or feeding suspect animals, but skin is intact

• Category II: minor scratches without bleeding from contact, or licks on broken skin

• Category III: one or more bites, scratches, licks on broken skin, or other contact that breaks the skin; or exposure to bats

Post-exposure care to prevent rabies includes cleaning and disinfecting a wound, or point of contact, and then administering anti-rabies immunisations as soon as possible. Anti-rabies vaccine is given for Category II and III exposures. Anti-rabies immunoglobin, or antibody, should be given for Category III contact, or to people with weaker immune systems. When humans are exposed to suspect animals, attempts to identify, capture or humanely sacrifice the animal involved should be undertaken immediately. Post-exposure treatment should start right away and only be stopped if the animal is a dog or cat and remains healthy after 10 days. Animals that are sacrificed or have died should be tested for the virus.

Infection

Human's susceptibility to any disease depends on many factors starting at the most basic level of innate resistance. For example, humans are innately resistant to PRV and TGE because our cells do not have the particular characteristics of pig cells that enable PRV and TGE virus to infect the cells and cause disease. Many pig diseases fit into this category, however, for some we do not have this innate resistance and we are susceptible. Fortunately, just because the hazard exists does not mean that any time the organism is present in the environment that we are going to be infected and to get sick. Out general health status and (specifically our immune status) provides further protection. In addition, we must be infected with an adequate dose of the organism or it will fail to establish an infection.

Take-Home Message

Viruses are classified depending on how they look under a microscope, their outer shell, and the type of genetic material (RNA or DNA). Viruses cannot multiply outside the host cell. Outside the host they can live for only a few hours to a few weeks.

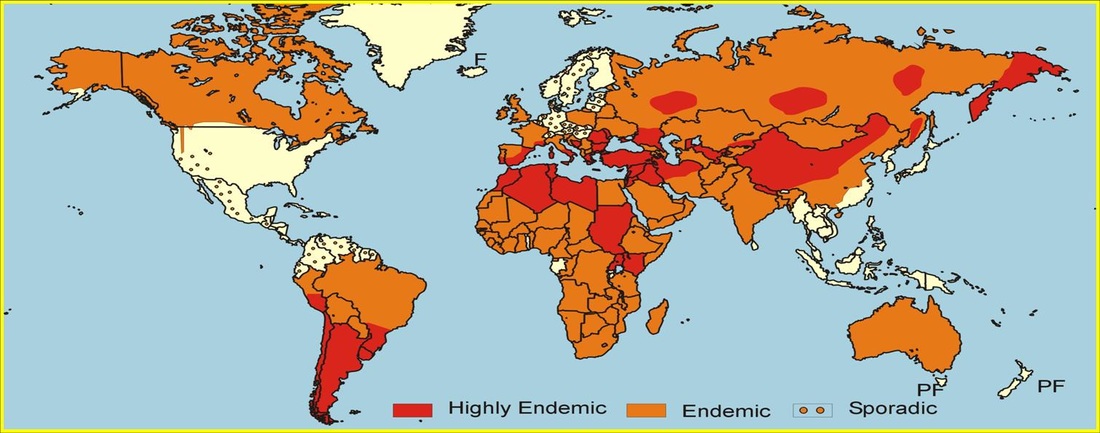

Nipah: This newly identified virus has killed about 103 people in Malaysia. The epidemic started in 1997 with an outbreak of encephalitis among pig-farm workers in the state of Perak in Malaysia. The virus, which is transmitted from pigs to humans, swept through more than half of Malaysia's thirteen states. By May 1999, the Malaysian Ministry of Health, in association with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, reported 258 cases of encephalitis in adults, with a case-fatality rate of almost 40%. Initially, the causative agent was thought to be Japanese encephalitis virus because that was common in the area. The abnormal (for JEV) clinical signs led researchers to search for another agent. They eventually identified another virus that they named Nipah after the Malaysian village where it claimed its first victim. To prevent its spread, the Malaysian government ordered the destruction of about 1 million pigs. The virus has been isolated from humans, pigs, dogs, cats, horses, goats and bats and it has basically ruined the pig-farming industry in most of Malaysia. Nipah virus has not been identified in the USA.

Menangle: This is a very rare virus and only one outbreak in New South Wales, Australia has been identified. It caused flu-like symptoms in people. It is also carried by fruit bats.

Influenza: The first thing to realize is that swine flu and human influenza (Spanish Flu which killed 20 million to 40 million people in 1918 and 1919) were not caused by the same virus--they had a common ancestor. However, the epithelial cells of pigs seem to have receptors for both human and avian influenza and that supports the idea that pigs may be the mixing vessel wherein human pathogens my develop. To keep on top of the situation public health officials should monitor human clinical flu outbreaks and determine which type is involved.

Hepatitis-E: HEV was experimentally reproduced in swine in Russia in 1990. Subsequently, studies by US and Nepalese investigators in the Kathmandu Valley found that 33% of pigs had evidence of past or current infection. About 9% of pig workers had antibodies to the virus. Work in the USA seems to indicate that swine HEV is genetically very distinct from the HEV strains previously compared. It is very closely related to HEV US-1 and US-2. Indications are that swine HEV and the US human HEV strains together form a distinct branch. Experimentally, cross-species infection has been demonstrated for this new branch of HEV strains. Therefore, it is possible that swine-to-human HEV infection is occurring. HEV has the potential to infect people working with pigs. Results of recent sero-survey of large-animal veterinarians in the mid-west revealed that about 10% had antibodies to HE-these infections were probably entirely subclinical. The risk that HEV represents to people on hog farms, or the risk that it may be transmitted to their families or to other members of the community, is unknown. There are no data suggesting economic losses due to HEV infections in swine.

Encephalomyocarditis: (EMC) It is an RNA virus. It is rare in humans and not fatal.

Internal Parasites

Ascariasis: Caused by the worm Ascaris suum. Ingestion of the ova sets up a transient infection in humans. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene.

Balantidiasis: Caused by Balantidium coli. Humans are very resistant but swine are major source for humans. An infection is acquired by ingestion of the parasite. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene

Toxoplasmosis: Caused by Toxoplasma gondii. Workers can acquire an infection by eating pork containing cysts or ingesting the oocysts excreted by cats that live around the hog operation. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene and not eating undercooked pork.

Cryptosporidiosis: Caused by a coccidian protozoa, Cryptosporidium parvum, that causes diarrhea, vomiting, wasting, and abdominal pain. Some people may have no symptoms. In the worst cases it can cause severe prolonged diarrhea with wasting and death. It is transmitted through contaminated water and the directly through the fecal-oral route. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene.

Fungi

Ringworm: Caused by a variety of fungi. The commonest cause in swine is Microsporum nanum. In humans they cause scaly lesions with itching and hair loss. It is easily prevented by hand washing and general personal hygiene.

Mites

Scabies: In swine the organism is Sarcoptes scabiei var. suis which can live on people but not reproduce on them. In other words, humans are a dead-end host for the pig scabies mite.

Rabies

This needs to be included in the list of zoonotic diseases, but is often neglected when discussing diseases that can be spread from animal to person and vice-versa. Rabies is a zoonotic disease (a disease that is transmitted to humans from animals) that is caused by a virus. Rabies infects domestic and wild animals, and is spread to people through close contact with infected saliva (via bites or scratches) There have been cases of pigs who tested positive for rabies. There is not a pig approved vaccination, but many vets use the rabies vaccine off label to protect pet pigs from any exposure.

Symptoms: The first symptoms of rabies are flu-like, including fever, headache and fatigue, and then progress to involve the respiratory, gastrointestinal and/or central nervous systems. In the critical stage, signs of hyperactivity (furious rabies) or paralysis (dumb rabies) dominate. In both furious and dumb rabies, some paralysis eventually progresses to complete paralysis, followed by coma and death in all cases, usually due to breathing failure. Once symptoms of the disease develop, rabies is fatal. Without intensive care, death occurs during the first seven days of illness.

Treatment after exposure: Recommended treatment to prevent rabies depends on the category of the contact:

• Category I: touching or feeding suspect animals, but skin is intact

• Category II: minor scratches without bleeding from contact, or licks on broken skin

• Category III: one or more bites, scratches, licks on broken skin, or other contact that breaks the skin; or exposure to bats

Post-exposure care to prevent rabies includes cleaning and disinfecting a wound, or point of contact, and then administering anti-rabies immunisations as soon as possible. Anti-rabies vaccine is given for Category II and III exposures. Anti-rabies immunoglobin, or antibody, should be given for Category III contact, or to people with weaker immune systems. When humans are exposed to suspect animals, attempts to identify, capture or humanely sacrifice the animal involved should be undertaken immediately. Post-exposure treatment should start right away and only be stopped if the animal is a dog or cat and remains healthy after 10 days. Animals that are sacrificed or have died should be tested for the virus.

Infection

Human's susceptibility to any disease depends on many factors starting at the most basic level of innate resistance. For example, humans are innately resistant to PRV and TGE because our cells do not have the particular characteristics of pig cells that enable PRV and TGE virus to infect the cells and cause disease. Many pig diseases fit into this category, however, for some we do not have this innate resistance and we are susceptible. Fortunately, just because the hazard exists does not mean that any time the organism is present in the environment that we are going to be infected and to get sick. Out general health status and (specifically our immune status) provides further protection. In addition, we must be infected with an adequate dose of the organism or it will fail to establish an infection.

Take-Home Message

- Wash your hands before you eat or smoke.

- Wear gloves when you handle infectious material, e.g., excretion material.

- Wash your work-clothes at work or bring a change of clothes and keep the soiled clothing away from your pet pig.

- Treat and cover all cuts and lacerations immediately.

- Do not eat near pig pens, especially those you do not know.

- Seek treatment if you are ill and tell the physician that you work with hogs.

- Keep children out of the pig area or insist they wear a protective gear while visiting stranger pigs.

- Never kiss a pig when you don’t know where this pig has been!

- Inform immuno-compromised people of the hazards of pig farming.

- If you are sick, don’t risk giving the illness to your pig. Stay away for a bit and allow yourself time to recover. Do not share spoons or handle your pig a lot while ill.

- Remember, some of these diseases/illnesses can be found in the soil of your own backyard. You don't have to live in an exotic location for your pig to become infected. Vaccinate for those that vaccinations are available and talk to your vet about which diseases are found in your area.

All information collected and/or written by Brittany Sawyer

Influenza- You CAN give your pig the flu!

The Flu Can Spread from Pigs to People and from People to Pigs

Preventing the Spread of Flu Viruses Between People and Pigs

Like everyone else, animal caretakers tending pigs should get annual seasonal influenza vaccines. Although vaccination of people with seasonal influenza vaccine probably will not protect against infection with variant influenza viruses (because they are substantially different from human influenza A viruses), vaccination is important to reduce the risk of transmitting seasonal influenza A viruses from ill people to other people and to pigs. Seasonal influenza vaccination might also decrease the potential for people or pigs to become co-infected with both human influenza viruses and influenza viruses from pigs. Such dual infections are thought to be the source of reassortment of two different influenza A viruses which can lead to a new influenza A virus that has a different combination of genes, and which could pose a significant public or animal health concern.

Other routine measures to take:

If you must come in contact with pigs while you are sick, or if you must come in contact with pigs that are known or suspected to be infected, or their environment, you should use appropriate protective measures (for example, wear protective clothing, gloves, masks that cover your mouth and nose, and other personal protective equipment) and practice good respiratory and hand hygiene.If you or your family members become sick with flu-like symptoms and need medical treatment, take the following steps:

Almost all influenza cases in humans are caused by human flu viruses, not viruses from swine. However, if you are infected with an influenza virus of animal origin, the health department will want to talk with you about your illness and make sure that other people you live and work with are not sick with the same virus.

Source: Diseases of Swine, 10th edition

http://www.cdc.gov/flu/swineflu/people-raise-pigs-flu.htm

- Human flu viruses can infect pigs and can introduce new flu viruses into the swine population.

- The flu viruses that normally circulate in pigs can infect people, but this is not common.

- In 2005 and 2006, three cases of infection with flu viruses that normally circulate in swine (“variant viruses”) were reported in people.

- Beginning in 2007, about three to four of these cases were reported per year. This increased reporting may partially be because human infection with novel (non-human) flu viruses became nationally notifiable in 2007. That means that when a human infection with a non-human influenza virus is detected in people, it must be reported to federal authorities.

- In 2012, 313 variant cases were reported to CDC, the largest number of cases reported in a single year.

- The flu viruses that commonly spread in humans are different from the ones that spread in pigs.

- People who get vaccinated annually against human influenza can still get sick from swine influenza viruses.

- Pigs that have been vaccinated for swine influenza can still get sick from some human influenza viruses.

- When people are infected with variant flu viruses, the symptoms are basically the same as those caused by illness from human influenza viruses and can include fever, cough, body aches, headaches, fatigue and runny or stuffy nose. There may also be vomiting or diarrhea.

- Most reported cases of human infection with variant viruses have occurred in people who have been near infected pigs in public settings such as fairs or petting zoos, or who work directly with infected pigs.

- Investigations of human cases of infection with variant viruses are routine. These investigations are designed to determine if the flu virus in question is spreading from person to person. It is important to know if flu viruses common among pigs are spreading among people so that cases in other people can be prevented.

Preventing the Spread of Flu Viruses Between People and Pigs

Like everyone else, animal caretakers tending pigs should get annual seasonal influenza vaccines. Although vaccination of people with seasonal influenza vaccine probably will not protect against infection with variant influenza viruses (because they are substantially different from human influenza A viruses), vaccination is important to reduce the risk of transmitting seasonal influenza A viruses from ill people to other people and to pigs. Seasonal influenza vaccination might also decrease the potential for people or pigs to become co-infected with both human influenza viruses and influenza viruses from pigs. Such dual infections are thought to be the source of reassortment of two different influenza A viruses which can lead to a new influenza A virus that has a different combination of genes, and which could pose a significant public or animal health concern.

Other routine measures to take:

- Wash your hands frequently with soap and running water before and after exposure to animals,

- Avoid close contact with animals that look or act ill, when possible, and

- Avoid contact with pigs if you are experiencing flu-like symptoms.

If you must come in contact with pigs while you are sick, or if you must come in contact with pigs that are known or suspected to be infected, or their environment, you should use appropriate protective measures (for example, wear protective clothing, gloves, masks that cover your mouth and nose, and other personal protective equipment) and practice good respiratory and hand hygiene.If you or your family members become sick with flu-like symptoms and need medical treatment, take the following steps:

- Contact your health care provider and let them know about your symptoms and that you work with swine. Your doctor may prescribe treatment with influenza antiviral medications and may want a nose and throat specimen collected from you for testing at your state health department.

- Avoid or limit contact with household members and others until you have been fever-free for 24 hours without the use of fever reducing medications, and avoid travel.

- Practice good respiratory and hand hygiene. This includes covering your mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or sneezing and putting used tissues in a waste basket. If tissues are not available, cough or sneeze into your upper sleeve. Always wash your hands after coughing or sneezing. This is to lower the risk of spreading whatever virus you have to others.

- Avoid or limit contact with pigs as much as possible. Stay away from pigs for 7 days after symptoms begin or until you have been fever-free for 24 hours without the use of fever reducing medications, whichever is longer. (This is to protect your pig(s) from getting sick.)

Almost all influenza cases in humans are caused by human flu viruses, not viruses from swine. However, if you are infected with an influenza virus of animal origin, the health department will want to talk with you about your illness and make sure that other people you live and work with are not sick with the same virus.

Source: Diseases of Swine, 10th edition

http://www.cdc.gov/flu/swineflu/people-raise-pigs-flu.htm

The AVMA discusses a case of meningitis that was caused by streptococcus suis in a pig. 05/2006

https://www.avma.org/News/JAVMANews

https://www.avma.org/News/JAVMANews

Pasteurellosis and how this can affect YOU

Bacteria of the genus Pasteurella were recognized as disease causing organisms in 1880 when Louis Pasteur established Pasteurella multocida (PM) as the etiological agent of fowl cholera and the genus was subsequently named in his honor. The importance of PM has been known for more than 125 years, yet this bacterium continues to significantly impact swine health worldwide as a cause of atrophic rhinitis (AR) and pneumonia. You can read more about atrophic rhinitis by clicking here and more about pneumonia by clicking here.

Why is this so important and included in the zoonotic section of the website? Pasteurella Multocida is an important zoonotic agent and is responsible for most human infections related to animal bites or scratches. Dogs and cats are the predominant source, but infection following bites from pigs, rabbits, rats and various wild animals have also been reported. This can be an accidental head swipe resulting in a puncture wound or scratch from a pigs tusk.

Human pasteurellosis most often presents as skin or soft tissue infection, typically with rapid onset, characterized by inflammation, swelling and purulent exudate. Most serious manifestations generally limited to immunocompromised patients include septicemia, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, meningitis and peritonitis. PM is not a usual constituent of the human upper respiratory tract, but strains genetically identical to those found in the swine reservoir are frequently isolated from pig farmers and inhabitants of regions with intensive pig breeding. Most human carriers remain healthy, but PM may also be associated with acute or chronic respiratory disease. It has been proposed that pneumonic pasteurellosis be considered an occupational disease. Appropriate precautions should be observed by persons who have contact with swine infected with PM, particularly those who are immunocompromised.

The epidemiology of PM in swine is not well understood. The organism is present in practically ALL herds and can be detected in the nose and tonsils of healthy animals. Aerial transmission has been postulated (suggested) but only low numbers of airborne PM could be recovered in large pig operations. Although the bacterium may occasionally be spread via aerosols, nose to nose contact is probably the most common route of infection. PM can persist in herds for months or even years, sometimes with vert little evidence of the disease. Some evidence suggests occasional interspecies spread of avian, bovine, ovine and porcine strains. Rodents, cats, dogs and other hosts that commonly carry PM should be considered possible sources of exposure to pigs. Whether or not healthy human carriers can transmit PM to swine is unknown.

Molecular typing techniques have been used to better understand the epidemiology of PM in pigs but comparisons among studies are problematic because there is no widely adopted and standardized method, many of the studies fail to provide a quantitative measure of diversity. Nonetheless, it appears that there is limited genetic diversity. PM poorly colonizes (finds a place and stays there) the respiratory tract in the absence of preexisting damage to the mucosa. In vitro studies using swine cells from the nasal cavity or teaches consistently demonstrate little to no attachment. (Chung et al. 1990; Frymus et al. 1986; Jacques et al. 1988; Nakai et al. 1988) The tonsil, particularly the tonsils crypt, appears to be the preferred habitat of PM in swine and may protect bacteria from inflammatory cells or act as a physical barrier to removal by swallowing.

What does this mean for you? If your pig purposefully or accidentally pierces your skin, YOU are at risk for developing this PM infection since it can be passed from pig to person, typically in the form of a bite. A pig bite should NOT be closed with "glue" like closure agents, often times, bites or larger gashes are sutured, but that may still trap the bacteria inside and allow it to travel throughout the body resulting in sepsis which can be life threatening if not treated. Typically doctors who are aware the injury was sustained by an animal bite know to leave the wound open unless there are extenuating circumstances that require sutures/wound closure. (If the benefit outweighs the risk) If you are bit by a pig and exhibit any signs of infection, YOU NEED TO SEE YOUR DOCTOR and let them know whats going on and how it happened so you can be treated appropriately with the right medications. Most of the time, doctors aren't prepared for a pig bite and do not know the diseases that can be passed along to humans. Just something to keep in mind since it is KNOWN to happen.

Written by Brittany Sawyer 2016

Source: Diseases of Swine, 10th edition

Veterinarians Guide for animal owners

Why is this so important and included in the zoonotic section of the website? Pasteurella Multocida is an important zoonotic agent and is responsible for most human infections related to animal bites or scratches. Dogs and cats are the predominant source, but infection following bites from pigs, rabbits, rats and various wild animals have also been reported. This can be an accidental head swipe resulting in a puncture wound or scratch from a pigs tusk.

Human pasteurellosis most often presents as skin or soft tissue infection, typically with rapid onset, characterized by inflammation, swelling and purulent exudate. Most serious manifestations generally limited to immunocompromised patients include septicemia, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, pneumonia, meningitis and peritonitis. PM is not a usual constituent of the human upper respiratory tract, but strains genetically identical to those found in the swine reservoir are frequently isolated from pig farmers and inhabitants of regions with intensive pig breeding. Most human carriers remain healthy, but PM may also be associated with acute or chronic respiratory disease. It has been proposed that pneumonic pasteurellosis be considered an occupational disease. Appropriate precautions should be observed by persons who have contact with swine infected with PM, particularly those who are immunocompromised.

The epidemiology of PM in swine is not well understood. The organism is present in practically ALL herds and can be detected in the nose and tonsils of healthy animals. Aerial transmission has been postulated (suggested) but only low numbers of airborne PM could be recovered in large pig operations. Although the bacterium may occasionally be spread via aerosols, nose to nose contact is probably the most common route of infection. PM can persist in herds for months or even years, sometimes with vert little evidence of the disease. Some evidence suggests occasional interspecies spread of avian, bovine, ovine and porcine strains. Rodents, cats, dogs and other hosts that commonly carry PM should be considered possible sources of exposure to pigs. Whether or not healthy human carriers can transmit PM to swine is unknown.

Molecular typing techniques have been used to better understand the epidemiology of PM in pigs but comparisons among studies are problematic because there is no widely adopted and standardized method, many of the studies fail to provide a quantitative measure of diversity. Nonetheless, it appears that there is limited genetic diversity. PM poorly colonizes (finds a place and stays there) the respiratory tract in the absence of preexisting damage to the mucosa. In vitro studies using swine cells from the nasal cavity or teaches consistently demonstrate little to no attachment. (Chung et al. 1990; Frymus et al. 1986; Jacques et al. 1988; Nakai et al. 1988) The tonsil, particularly the tonsils crypt, appears to be the preferred habitat of PM in swine and may protect bacteria from inflammatory cells or act as a physical barrier to removal by swallowing.

What does this mean for you? If your pig purposefully or accidentally pierces your skin, YOU are at risk for developing this PM infection since it can be passed from pig to person, typically in the form of a bite. A pig bite should NOT be closed with "glue" like closure agents, often times, bites or larger gashes are sutured, but that may still trap the bacteria inside and allow it to travel throughout the body resulting in sepsis which can be life threatening if not treated. Typically doctors who are aware the injury was sustained by an animal bite know to leave the wound open unless there are extenuating circumstances that require sutures/wound closure. (If the benefit outweighs the risk) If you are bit by a pig and exhibit any signs of infection, YOU NEED TO SEE YOUR DOCTOR and let them know whats going on and how it happened so you can be treated appropriately with the right medications. Most of the time, doctors aren't prepared for a pig bite and do not know the diseases that can be passed along to humans. Just something to keep in mind since it is KNOWN to happen.

Written by Brittany Sawyer 2016

Source: Diseases of Swine, 10th edition

Veterinarians Guide for animal owners